In a sweaty township gym where Nelson Mandela once trained as a young boxer, athletes are still pumping iron today, inspired by the peace icon’s example as he fights for his life in hospital.

In the early 1950s, a youthful Mandela worked out on week nights at the Donaldson Orlando Community Centre, or the “D.O.” as it’s still affectionately known.

Spartan and slightly run down, the walls ooze with the intermingled history of sport, community life and the decades-long fight against apartheid oppression.

It was here that Mandela came to lose himself in sport to take his mind off liberation politics.

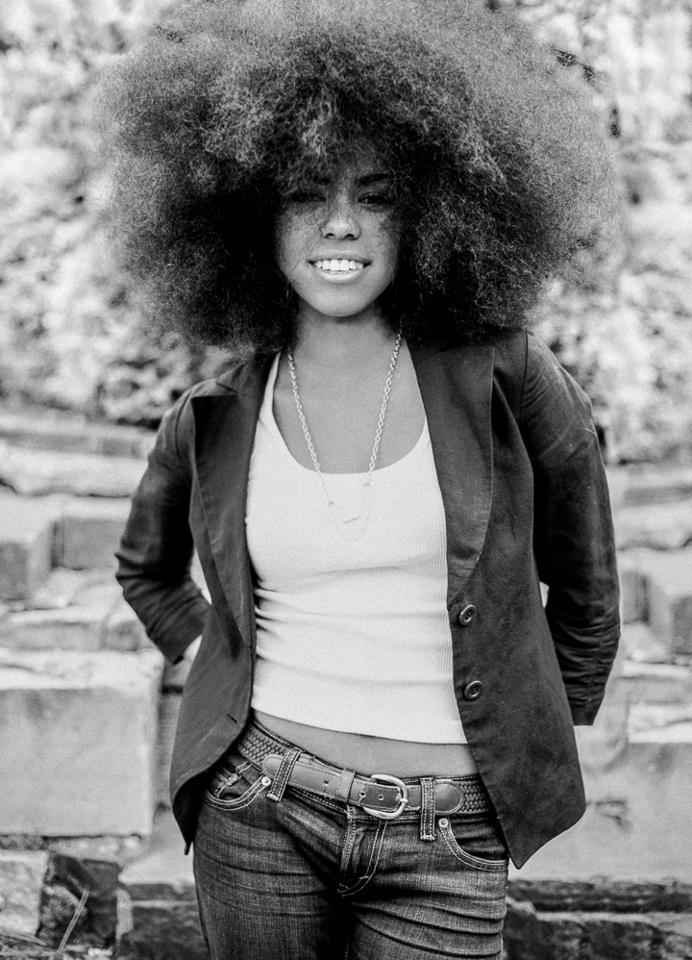

Nestled in the heart of South Africa’s largest township just south of Johannesburg, the community centre was also where famous African songbirds like Miriam Makeba and Brenda Fassie first performed.

The 1976 uprising against the imposition of the Afrikaans language in black schools were planned from the D.O. as Mandela and other leaders languished in apartheid jails.

“Here, look, these are the very same weights Madiba used for training,” proud gym instructor Sinki Langa (49) says.

“They have lasted all these years,” he said as he added another set to a bar his fellow trainee Simon Mzizi (30) was using to furiously bench-press, sweat dripping down his face.

Nearby, other fitness enthusiasts worked out to the tune of soothing music which, unusually for a gym, included opera.

‘Drenched with sweet memories’

The D.O. – or Soweto YMCA as it is called today – opened its doors in 1948, the same year the apartheid white nationalist government came to power.

Built with funds donated by Colonel James Donaldson, a self-made entrepreneur and staunch supporter of the now governing African National Congress, the D.O. centre includes a hall, and several sparsely furnished smaller rooms like the one where Mandela sparred as a young man.

Today the gym is housed in an adjacent hall, which was the original building on the grounds erected in 1932.

Mandela joined the D.O. in around 1950, often taking his oldest 10-year-old son Thembi with him.

In a letter to his daughter Zinzi, while on Robben Island where he spent 18 of his 27 years in jail, Mandela recalled his days at the gym.

“The walls … of the DOCC are drenched with the sweet memories that will delight me for years,” he wrote in the letter, published in his 2010 book Conversations with Myself.

“When we trained in the early 50s the club included amateur and professional boxers as well as wrestlers,” Mandela wrote to his daughter, who never received the letter because it was snatched by his jailers.

Training at the D.O. was tough and included sparring, weight-lifting, road-running and push-ups.

“We used to train for four days, from Monday to Thursday and then break off,” Mandela told journalist Richard Stengel in the early 1990s, while writing his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom.

When he was handed a life sentence in 1964, Mandela kept up the harsh regime of his training to stay fit and healthy.

“I was very fit, and in prison, I felt very fit indeed. So I used to train in prison … just as I did outside,” Mandela said in a transcript of his conversation with Stengel, given to AFP by the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory.

Mandela was eventually released from jail in 1990 and in 1994 he was elected South Africa’s first black president.

‘He’s a fighter’

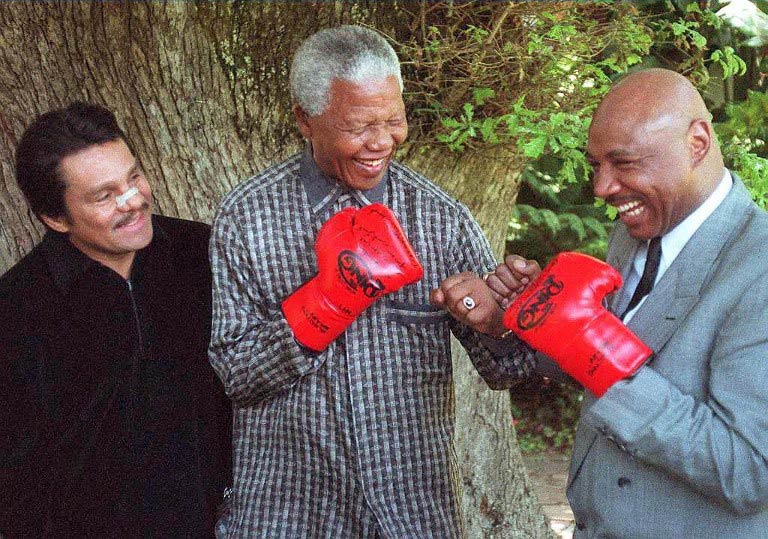

In Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela admitted he was “never an outstanding boxer”.

“I did not enjoy the violence of boxing as much as the science of it… It was a way of losing myself in something that was not the struggle,” Mandela wrote.

“Back in those days, boxing was very popular – it was part of that culture,” Shakes Tshabalala (81) who has been involved with the centre from the start told AFP.

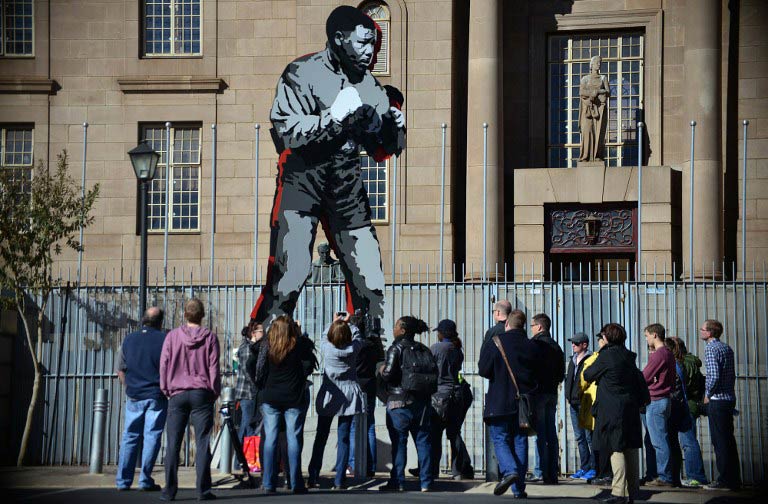

Pugilism always played a big part in Mandela’s life. At his house-turned-museum at 8115 Orlando West, boxing-related items like the WBC World Championship belt donated by Sugar Ray Leonard are on display.

Back at the centre, a new generation of youngsters are training.

Although few of them box today, they draw their inspiration from Mandela’s example in healthy living.

While the ailing 94-year-old statesman is battling a recurring lung infection, the gym-goers firmly believe the liberation icon will return for one last round.

“Mandela was a sportsman. This is why today he is still alive,” said gym instructor Langa.

“I am worried about him, but I know he’ll win. He’s a fighter,” he said.

Jan Hennop for AFP