‘Are yellow bones more beautiful than dark-skinned girls?’ screamed a recent headline the Sunday News. This followed a period in which both the media and public went into a frenzy discussing whether or not the current Miss Zimbabwe – given her dark complexion – was beautiful enough to represent the country. Now, I will not go into that discussion. Countless newspapers have already done this ad nauseam. But what I would like to talk about is a different side to this whole ‘yellow bone’ versus ‘dark cherry’ debate.

There is a new, implicit wave of ‘yellow bone’ bashing that’s going on, and things don’t look like they are about to change any time soon. If you don’t believe it, see here, here and countless other places where you will find piles of narrow-minded literature on this subject.

In recent years, Zimbabwean society caught onto this phrase, ‘yellow bone’. Suddenly, it is no longer sufficient to call light-skinned women just that: light-skinned. And many times, this derogatory and callous word is used in reference to light-complexioned women when they are compared to ‘black cherries’ or dark-skinned women, as they are disparagingly referred to themselves.

A different cat-calling experience

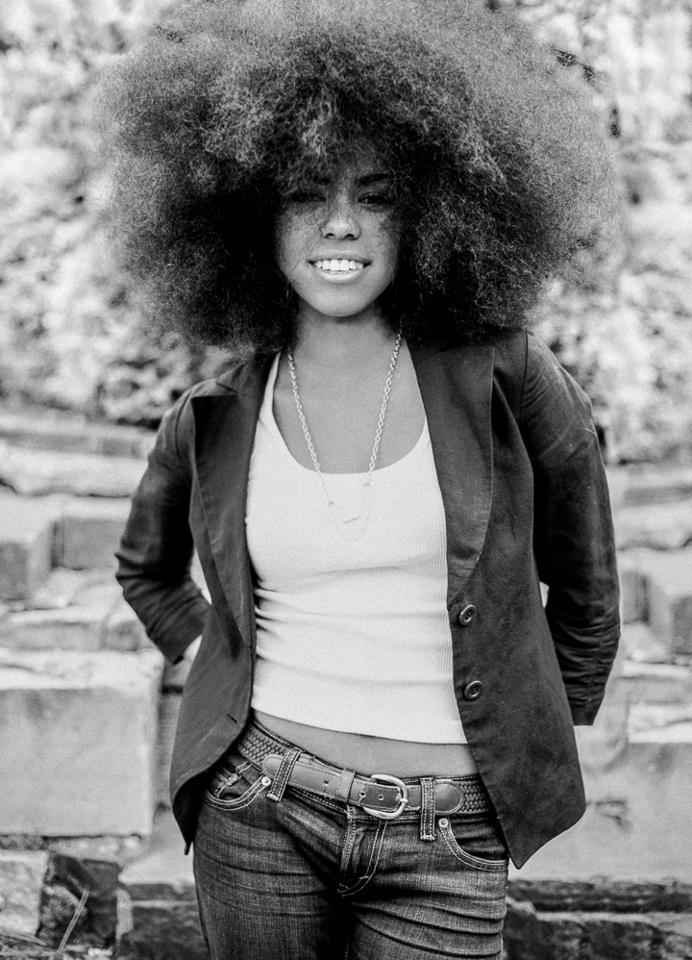

So my first real encounter with the term ‘yellow bone’ happened last year as I was minding my own business at a busy shopping centre. I walked past a vehicle in which sat three men who clearly had nothing better to do. One of them called out something inaudible to me and I kept walking. He called out again, and when that did not elicit a response from me, went on to open the car door and shout very loudly something along the lines of, “You might be a ‘yellow-bone’, but you certainly aren’t pretty after all!”.

A lot of men feel entitled to yell all kinds of things at women going about their business on the street. But this experience stood out for me for one reason: it seems I couldn’t get away with simply ignoring street heckles like any other woman would do, without being insulted a second time about my complexion.

Do those with a lighter complexion – the so-called ‘yellow bones’ – live in a cloud of appreciation? At the most superficial level, I find that light skin might be thought to carry a kind of halo around it. We see someone with an attribute that so many others desire, and by association, assume that they have been blessed in other departments too.

But there are a lot of prejudices that work against light-skinned women.

The ‘blondes’ of the black community

I have not been conferred with advantages throughout my life, and certainly, my life as a so-called ‘yellow bone’ woman has not been all sunshine and roses. Growing up as a light-complexioned, skinny girl, I had my fair share of insecurities. All around me I saw pretty girls who had beautiful curves and smooth skin. My conception of what constituted beauty was a combination of things ranging from physique to disposition of the heart.

To put it in context, we the so-called ‘yellow bones’, are often considered to be the ‘blondes’ of the black community. You constantly have to prove yourself, because for some reason, something about your complexion gives the impression that you have neither brains nor brawn.

In a lot of places, I am automatically considered ‘musalad’. People often have weird assumptions that you don’t speak Shona or eat sadza and maguru (tripe) which just happens to be my favourite food. Neither do they think you can cook sadza! I have a distinct memory of a time many years ago, when I first went to my husband’s rural home. The neighbours flocked to see the new muroora. There was a lot of whispering, mainly things to do with my complexion. It did not help that I wear spectacles that tint in the sun. But the killer for me came from one elderly woman who took my hand into her calloused one, analysed my palm and asked rhetorically if such a pale-looking hand could mona (cook) sadza (insert eye roll here). Follow-up question:

Elderly woman: How is it that you are so light in complexion?

Me: Er, genetics?

Yes, I do sometimes get asked such moronic questions and it’s just plain exhausting. I mean, really!?? Is there any link between one’s complexion and one’s ability to flex wrist muscles?? I have yet to establish the connection between the colour of the skin on my hand and my ability to cook sadza, but so far there haven’t been any complaints in my house!

Stereotypes, stereotypes!

Don’t get me started on the ‘vakadzi vatsvuku vakasaroya, vanohura’ (light-skinned women are either witches or promiscuous) stereotype. This particular one I often hear from other women.

Other times, I am forced to justify my complexion, until it becomes pointless. I find that there is often an automatic assumption that light-complexioned women use skin-lightening products. It’s almost like how people generally assume that all obese people are that way because they overeat.

On lucky days, I am just mistaken for a mixed-race or coloured person. But on not so lucky days, sometimes people ask outright what cream or injectable I have used that has lightened my complexion so perfectly and uniformly. I had an experience once, where a woman in a hair salon very rudely took my hand and began to analyse my knuckles. Apparently, no matter how good a skin-lightening product you use – knuckles, elbows and knees will always give a user of such products away.

In my experience, fellow women are the most brutal with their judgments and opinions about a so-called ‘yellow bone’. There is a hair salon I stopped going to, because its owner always had colourful things to say and ‘joke’ about my complexion, all the while patting me on the back and calling me her ‘sister’. This was somehow supposed to take away the sting in her words? She joked once that the Diproson cream that my hairdresser loved to apply to my scalp was not only doing wonders for my dandruff, but also my facial complexion.

It appears that in some spaces, you just can’t be innocently light-skinned anymore. I have never used a skin-lightening product in my life, yet this stigma hangs over my head until people prove for themselves, in some way, that I am authentic. Yes, there is a scourge where a lot of women have started bleaching themselves, probably to conform to some elusive societal construct of beauty. But it is also interesting that at least in Zimbabwe, this phenomenon applies to women only. Nobody seems bothered about ‘yellow bone’ guys.

Nevertheless, I doubt that I will ever understand or be able to explain the fascination obsession with ‘yellow bone’. I could go on and on about some of the hurtful experiences I have had, just because people ascribe to me the term ‘yellow bone’. But I will stop here and highlight that the so-called ‘yellow bones’ are human, like everybody else. We feel things too.

All I can say is that we should all be mindful of the fact that what is considered beautiful is socially determined. This can hopefully help us to overcome our biases, regardless of our inherited physical traits.

Natasha Msonza is an information activist and communication strategist passionate about human rights and social justice. She blogs at Stashsays.wordpress.com. This post was first published on Her Zimbabwe.