“When he talks the breeze ceases and the roof trembles. He commands the crippled to rise, and they rise. He lays his fingers on the blind, and they see. He touches a widow’s sick son, and he is healed.”

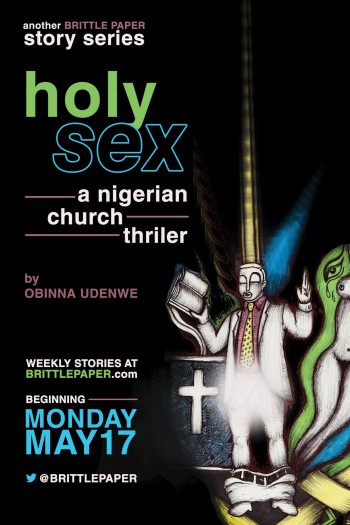

“He” is Pastor Samuel, the protagonist of a new fiction series, Holy Sex, that is using the erotic genre to examine the influence and power that the church pastor has over women’s lives in contemporary Nigerian society.

Published by Brittle Paper, an African literary blog, editor Ainehi Edoro explains that the fictional pieces key into an important social phenomenon. Wealthy and operating intimately in people’s lives, pastors are equivalent “to Oprah or they are Dr Phil… they give people a sense of hope,” Edoro explains.

The author, Obinna Udenwe, is the first to eroticise the Nigerian church in fiction, according to Edoro.

Your pastor is handsome. His nose is finely chiselled. His clear white eyeballs are draped in long eyelashes. His lips are full and sensuous. His broad shoulders fill out his designer suits. And when he doesn’t wear a tie, his 22-carat gold necklace sparkles in the reflection of the glass pulpit. A thick gold ring on which is mounted a cross and a bleeding heart adorns the finger he uses to swipe the iPad screen during his sermons

Holy Sex, episode one

Shaming the church?

Throughout the series Pastor Samuel has numerous affairs under his wife’s nose and extorts money from women in exchange for sex. The author describes female characters dressing in “plunging necklines” for Sunday service, with some antics resulting in unwanted pregnancies.

In episode two, one woman’s monologue reads: “To be perfectly honest, who doesn’t want to sleep with God’s anointed, these days?”

Was injecting taboo into the social power-centre of the church meant ruffle feathers? No, says Edoro, it’s playful fiction and not meant to be threatening: “It’s partly about the sex, it’s partly about the system,” she explains. The church has a certain power over women’s bodies, but as an editor didn’t mean to offend, just to encourage people “to think”.

Readers of Holy Sex have certainly recognised some truth in Udenwe’s tales: “I am dumbfounded, but this is exactly a replica of what ladies see in Nigerian churches – it is such a shame,” writes Amaka, a commenter on Brittle Paper.

Anonymity

Though the series has been extremely popular, most online readers were not comfortable commenting publicly or sharing the link via Facebook or Twitter, says Edoro.

Anonymity via e-readers and the internet has been attributed to the runaway success of books like Fifty Shades of Grey, but in Nigeria blogs read in private are the main way people like to consume erotica, Edoro adds.

He continues to come to your house once a week. Sometimes he sleeps over. He asks for money. You give him double of whatever number he requests. You gossip with your friends and tell them everything. You tell them that no one kisses like him. They envy you.

So this Saturday, Pastor Samuel visits your house. You’ve just paid a lot of money into his account that afternoon. You also agreed to fund his trip to Sweden for an evangelical conference, so he has come to say thank you for paying four million naira into his account

Holy Sex, episode five

Others who’ve made their names writing about love and sex in Nigeria include “romance author” Kiru Taye, based in London but specialising in “multicultural romance set in Africa”, and Dames Caucus who describes her style as “telling fictional stories laced with a little sex”.

Then there’s Abuja-based Cassava Republic Press who’ve set up a romance imprint. The team made a bundle of love and romance stories free to download on Valentine’s Day this year, and say their aim is to demonstrate “that romance can be empowering, entertaining, and elegantly written”.

Caucus, real name Vickie Aluta-Obueh, publishes steamy blogposts twice a month but wishes she could do more. She thinks that blogs are the preferred way for Africans to consume erotica because they’re often free to access, and, she says, can be printed out and added to people’s “naughty stash”.

Both Aluta-Obueh and Edoro talk about erotica being enjoyed by both men and women alike – unlike in the west, where the market is largely divided and marketed along gender lines.

Playing catch-up

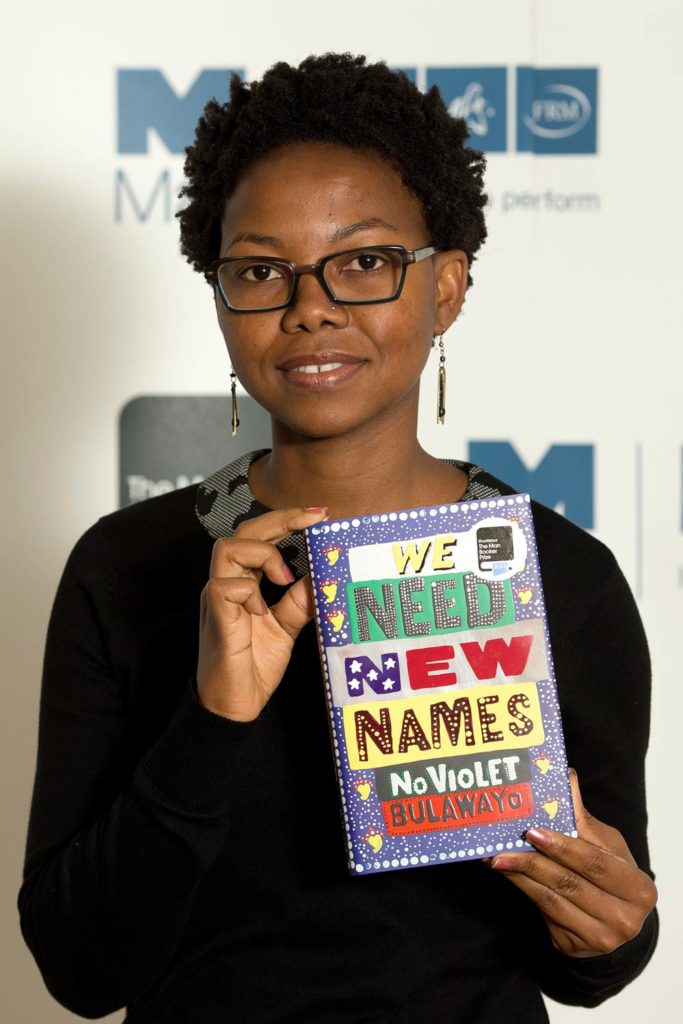

African erotic fiction is very much in it’s infancy, according to Edoro, who says it has a long way to go to catch up with Nollywood or the music industry, who have both been successful in selling African desire for the mass market.

Edoro puts this down to African fiction still being the “preserve of the intellectual classes” and while some pop fiction , like sci-fi and fantasy, are starting to find their feet, the genre needs time to flourish.

She explains that the obstacles relate to the lack of investment in popular Nigerian writing, suggesting there’s little money for local authors beyond celebrated names like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Teju Cole.

Just as doubts begin to fog your mind, his hand, his long and smooth hand, wanders to your dress. He lifts it and reaches your thighs. You recoil, but he pulls you close.

Holy Sex, episode four

Writer Aluta-Obueh blames Nigerian culture’s conservative attitudes to sex for choking the market: “There are so many talented erotic writers out there but fear of being vilified curbs their zeal to write,” she says. But despite what she describes as a “hypocrisy” where “anything sexual is frowned upon”, her feedback from readers has been overwhelmingly positive.

A few other comments from the readers of Holy Sex suggests that a burgeoning market is out there for erotic fiction: “Brilliant. I cringed at holy milk each time but in Naija [Nigeria] reality is stranger than fiction”, wrote a user known as Snapes. “A lot about the ease of the writer convinces me of the validity of such a story. I really appreciate such creativity”, added another user, Olatunde.