by Wadeisor Rukato

On Thursday the 30th of April 2015, I stepped off a taxi coming from the Bree taxi rank in order to make my way toward the MTN taxi rank[1]. I was coming from Greenside, where I work as an intern for a consultancy firm.

Immediately, as I stepped onto the curb, I was stopped by an aggressive tap on my shoulder followed by loud commands of “Eh, I said stop”, “You must respect me”, “Look me in the eye” – from two black women.

I steadied myself quickly and realised that one of the women, the taller one, was dressed in the navy official uniform of the South African Police Services. The shorter one, with a bob-cut weave, was wearing an orange golf T-shirt and a reflective warrant officer vest. She was holding a clipboard and pen. They both had a threatening but smug look on their faces, like they had just caught a big fish.

“This is a stop and search. Open your bag now!”

Without really thinking about the legal procedure regarding bag searches or my ‘rights’, I hastily unzipped my bag and revealed its contents. The short one clumsily ran her hand through and asked: “Where is your passport?”

I panicked. In my now 19 years of living in South Africa, I had never been asked this question. I didn’t have my passport. I don’t walk around with it.

I did have my green book – my stamp of legality, the document that guarantees my status as a permanent resident of South Africa. I took it out, handed it to them and felt like I had narrowly escaped doom. Until a week before, I refused to carry my ID with me, for fear of losing it given how hard it was to get in the first place.

My ID was handed back to me. The two women seemed disappointed. Maybe I imagined this.

I moved to South Africa when I was three years old. I am now 22. I am Zimbabwean and my parents moved to the City of Gold in 1995 to realise what, for many Zimbabweans then, was the real potential of a South African dream.

My first experience with xenophobia was in primary school in the early 2000s. Names such as “Kwerekwere” and “Girigamba”[2] were pelted at me like stones by children both my age and skin color. Even as a child I knew that these terms were meant for a select few. They were used to “other” and alienate foreigners of a specific kind. While the white French foreign student who visited was welcomed with curiosity and admiration, I, a black African child, was labelled Kwerekwere. I was taunted and excluded.

Throughout the rest of my school career, I experienced a dizzying identity crisis. In junior high, I spent time dreaming of living in Soweto, Diepkloof, maybe Orlando. In this imagined life, I spoke fluent Zulu. My friends and I took a taxi to Ghandi Square or MTN taxi rank to get home. I arrived at school on Mondays with news of Thabo, the boy from the opposite street, and how he asked for my number over the weekend. If anything, this dream bears witness to how profoundly I longed to become a South African citizen. Simply to belong, wholly and indisputably.

By the time I entered grade 10 in 2008, my delusions had been completely dashed. In May of that year foreigners were violently assaulted in the Johannesburg township of Alexandra.

Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuave was set alight and became known as “the burning man.” The image of him on his knees and wrapped in flames appeared almost everywhere.

Pieces of land along highways in Johannesburg, Olifantsfontein and Midrand became lined with rows and rows of UNHCR refugee tents for the displaced and vulnerable.

Young boys and girls in my grade huddled in the cold autumn/winter mornings before class. There were conversations that sometimes involved making ‘arguments’ for why black, lower-class and African foreigners earned the contempt they were experiencing.

I was made hyper-aware of my identity as a black Zimbabwean. I wanted to simultaneously lash out and dissolve. I felt convicted in the symbolism of my decision to have taken Afrikaans instead of Zulu as my second additional language.

I felt frustrated, angry, disappointed, rejected.

Today, I proudly identify myself as a Zimbabwean and choose to describe myself as a Zimbabwean who grew up and lives in South Africa. I fully acknowledge the influence that being raised in South Africa has had on me. Given my familiarity and extensive experience in the country, it is, in many ways, home. Zimbabwe is, however, where I feel rooted, where I belong. I feel a responsibility to return there at the earliest opportunity in order to reacquaint myself with my country and contribute to its development.

My identity crisis has, in effect, been resolved.

I recently read a paper by Michael Neocosmos –The Politics of Fear and the Fear of Politics: Reflections on Xenophobic Violence in South Africa – in which he addresses the reasons for these xenophobic attacks.

While xenophobia in post-apartheid South Africa is generally understood in terms of economics, there is good reason to believe that it is a product of political discourse and ideology. Neocosmos points to “state or government discourse of xenophobia, discourse of South African exceptionalism and a conception of citizenship founded exclusively on indigeneity”.

The reckless and quite frankly deplorable statement made by King Goodwill Zwelethini in which he called for all foreign nationals to return to where they came from is a prime example. It demonstrates the power that leaders wield in terms of influencing the perceptions and actions of certain groups in society toward African migrants in the country.

I remain disillusioned and disgusted by the poor show of leadership and lack of both urgency and agency displayed by key government officials and the president himself when it came to honestly and effectively addressing the recent xenophobic violence. An honest dialogue on why African foreigners are specifically targeted in xenophobic attacks in this country will not occur until the role that leadership plays in sparking, influencing, curbing or dealing with xenophobia is understood.

The fear/dislike of and violence against African migrants is not a new phenomenon in South Africa. The March 2015 attacks are also not likely the last we will see. That’s why it is important to address the role of leadership in the perpetration of xenophobia.

[1] MTN Taxi Rank and Bree Taxi rank are two of the main taxi terminals in the Johannesburg CBD.

[2] A derogatory term used in South Africa to refer to foreigners, particularly from Zimbabwe.

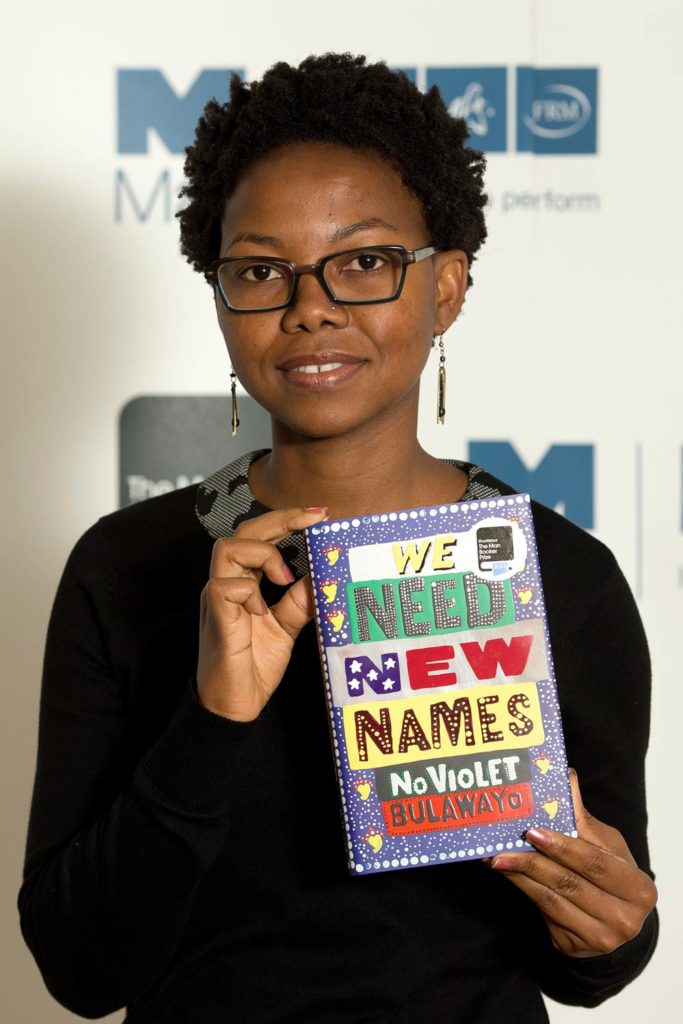

This post was first published on Brittle Paper, an African literary blog featuring book reviews, news, interviews, original work and in-depth coverage of the African literary scene. It is curated by Ainehi Edoro and was recently named a ‘go-to book blog’ by Publisher’s Weekly.