Eleanor Magaya was close to tears as she narrated how she has been continuously duped of her hard-earned cash by land barons.

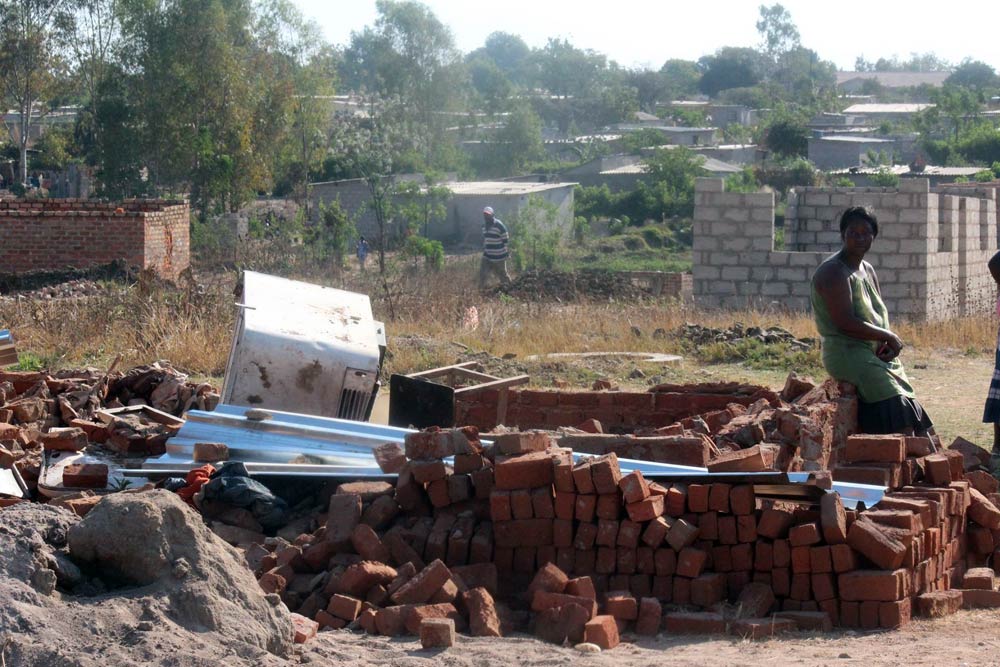

“Shuwa ndongoita mari yekurasa veduwee?” (Should I keep on pouring money into waste?) she asked. Her house is one of the thousands that were razed down by authorities in Chitungwiza, 25km north of Harare. Residents say their homes were built legally but authorities disagree. Many were evicted while others had their homes destroyed.

In September, the Chitungwiza Municipality authorities razed down 70 residential and business buildings at midnight. On the other end the Harare City Council served 324 settlers in the high-density suburb of Glen Norah with eviction notices. So far, the demolitions in Glen Norah have not proceeded as residents armed with axes and knobkerries faced off with the police, forcing them to withdraw. Residents in Epworth (15km outside Harare) also had their houses destroyed and are facing eviction from the local authorities.

Chitungwiza town clerk, George Makunde, highlighted the demolitions were set to rid the town of illegal structures which were built on undesignated areas. “As long as people continue to illegally occupying council land, the demolitions will continue,” says Makunde.

However, the Zimbabwe High Court ordered the government to stop the unconstitutional evictions and demolition process. On October 9, Judge Nicholas Mathonsi ruled that the authorities would need a court order to demolish any more houses. Hundreds of people have been left homeless as a result of this government exercise, and it is unclear whether they will be compensated for their loss of property or be relocated.

Illegal or not?

A government audit of illegal structures carried out in December 2013 found that more than 14 000 residential stands in and around Chitungwiza had been illegally sold by housing co-operatives, councillors and village leaders. Much of the land where stands were illegally created were meant for the construction of clinics, schools, cemeteries, roads and wetlands.

Following the release of the report in January, Local Government, Public Works and National Housing Deputy Minister Joel Biggie Matiza was quoted in the state-owned daily The Herald, committing to a “well organised, humane” demolition process that would ensure all affected families were offered alternative land.

The residents of these “illegal structures” have vowed to remain at their stands and are threatening to fight back the move.

“I will not go anywhere, I paid for this land, I am not staying here for free”, Nomatter Matikiti, a Chitungwiza resident, said.

Housing backlog

According to the audited report, Zimbabwe has a staggering housing backlog of 1.3-million and government and local authorities are struggling to keep pace with ever-increasing urban housing demands.

The report fingered land barons and proliferation of housing co-operatives who came in as gap fillers, amassing wealth for themselves .

Dzimbahwe Chimbga, programmes manager for the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights (ZLHR) said the demolitions “are quite devastating and disturbing as most of these people have only these homes and no other place to seek refuge. They happened at a time when not only the economy is ailing but as rains have also started,” said Chimbga.

The demolitions are said to have conjured memories of the 2005 Operation Murambatsvina which left 700 000 people displaced across the country.

Justice Mathonsi’s ruling on October 9 castigated the September demolitions, quoting section 74 of the Constitution: no person may be evicted from their home or have their home demolished without any order made after considering all relevant circumstances.

Mathonsi took a swipe at local authorities, saying that they have allowed illegal settlement to take root at the expense not only of the settlers but also organised urban planning and public health. He said local authorities are “now waking up and by force and power demolishing structures without regard to the law and human dignity“.

His decision has been applauded and although the demolitions have ceased for now, residents are yet to know whether they will still have a roof over their heads in the months to come.

Sally Nyakanyanga is a journalist in Zimbabwe.