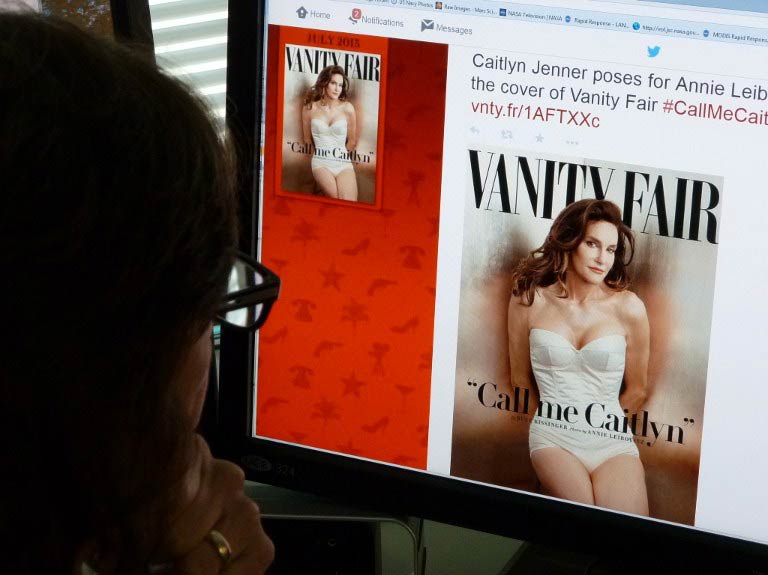

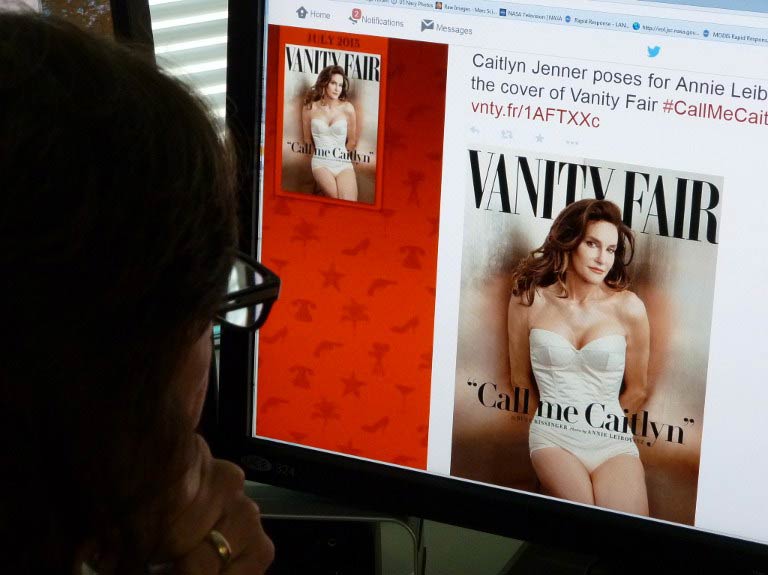

To understand the tasteless comedy that was the larger Nigerian reaction to Caitlyn Jenner, the woman Bruce Jenner introduced to the public on that iconic Vanity Fair cover, post-transition, you first have to understand the place of comedy in the country.

There is a lot that comedy placates in Nigeria. That we can laugh at our problems, that you can gather a broad class of Nigerians in a room and get them to laugh at class difference – the thieving politician sitting in the VIP section of that room is perhaps our most undervalued nationalistic tool.

A little more than a year ago, when the sexuality debate was sweeping through Africa, Nigerians felt it important to drawn clear boundaries. Yet for some reason, on this equally important humanity-defining issue, people largely chose the bliss of ignorance and comedy. For them, Caitlyn Jenner’s story was an America-is-crazy kind of thing. A problem with the world, but chiefly, other people’s problem.

And yet, the fact is in Nigeria, there are at least two public figures that disrupt the rigid boundaries of gender performance. Charles ‘Charly Boy’ Oputa is one of them; the entertainer who goes by the name His Royal Punkness regularly presents himself to the public as a person who exists in a gender flux; he wears make-up, a mostly punkish rock star kind. The other is Denrele Edun, a famous television presenter, who is even less subtle. He wears his shimmery gowns and long, gorgeous, sometimes outlandish hairpieces on the red carpet.

Nigerians, most of whom daily and with dedication watch Philipino love dramas where at least one character exists in a gender flux, are scandalised by these two local men who fearlessly dress across gender lines in a country where conforming to social expectations is almost non-negotiable. It is always interesting to read the classic Nigerian response to a Charly Boy photo shoot.

The common thread amongst people who live in this state of denial is God/Allah.

A majority of Nigerians construct their identities rigidly around religion. The world known to most Nigerians was created by God, filled by God with men, women and things for the men (to a large extent) and women to dominate. That world as it is known to most Nigerians is under threat from science in general and more specifically, people who think they are smarter than God. Anything that demands that their world be seen differently confirms the end of the world.

Asking that Nigerian to think of gender in the terms that Bruce’s transition demands is a threat. To find fun in it is the sane end of the stick, what lies beyond it can get scary. There is at least one reported case of the Nigerian public unleashing its wrath on an individual for not being ‘normal’. For being a man with woman breasts and, in essence, a witch.

There is a list of permitted ambiguities in the world as it is known to most Nigerians, and gender is not one of them.

From this convenient position, religion (and by religion, I mean Christianity and Islam) is the only accepted portal of history, and the past can be collectively rewritten. The very idea that people do not exist in straight categories of male and female becomes a dangerous foreign construct. Unfortunately, the idea of gender fluidity is not a new paradigm the free world cooked up.

The Yan Daudu exist. They are certainly not Nigeria’s only trangender people, not by a long shot, but they are the best evidence of a trans community in Nigeria. They have been part of the cultural fabric of pocket regions in Northern Nigeria for at least a century. They are pre-religion and have continued to exist post-religion. They cross dress, they take on complete female identities.

What Caitlyn should represent for them, is an audacity to claim the space of their individual realities. To make it anything more than a dying fringe culture.

And herein lies the question. Is what we have witnessed in the publicised transitioning of Bruce to Caitlyn a victory for the ‘global trans community’ in any real way? Does it mean anything for the Yan Daudu in Nigeria, or the Hijras in India?

“I am for people living in their truths” are words that have been increasingly used these past few weeks. I agree with the words. The only valid way to live in any case is in ways that are as truthful as one can muster. But as the world’s progressives cheer for Caitlyn, and we read the positive comments, can we also chip in a discussion on what this means to those small communities of people driven underground already by a witch hunt in places not the America? Is this too a victory for them? Are they, too, the earth?

Kechi Nomu writes from Warri, Nigeria. Her poems have appeared in Saraba Magazine and Brittle Paper.