Positive parenting had began to gain popularity among parents and teachers in the small Nigerian town of Sapele where I grew up, and my school was not going to be left behind.

So, every Valentine’s Day saw us assembled in our school hall to be treated to a film screening. Somehow, my teachers always managed to find the same kind of Nollywood story: good girls who kept themselves pure in the midst of the moral morass of youth and married handsome, wealthy men who loved them dearly for their virtue and would do anything to have them. In the late 1990s, the whole film show business seemed like such a big deal. But did it occur to anybody to question the choice of Nollywood as a viable Sex Ed aid? I I don’t think so.

Before the film played, it was mandatory that we live through 30 minutes or so of reorientation. The big colour television, placed at the centre of our school hall, would be on, the blue screen waiting, while a teacher – preferably the most religious or the most willing/concerned – talked to us about our changing bodies. By an unspoken consensus, on days like this – on other days too, but especially on days like this – everybody tried to avoid the use of certain words. And, standing in line, my breath held, my self-comportment overstretched, it was easy to understand why.

Those words, in their raw carnal forms, had terrible pitfalls. We had seen it happen many times; girls we knew, swallowed whole by the scotching intimacy of carnal words. Girls who knew about breasts and hips. Girls who we could tell, just by looking at them, that they were doing ‘it’. Girls who became pregnant. The general impression being that good girls just did not notice their bodies.

For the same reason that these words could just not be said, these films we saw were less about whatever narratives they managed to have and more about the overarching message. That narrative was: Good girls wait and are rewarded, bad girls end up with babies on their backs walking the streets looking lost. Good boys graduate, get great lives and have beautiful families, bad boys end up unfinished and angry at the world.

Then one year, our ‘exposed’ Home Economics teacher brought back a new movie Yellow Card (Zimbabwean) from one of her trips to Lagos. That film represents for me, to this day, a kind of epiphany. At school that day, I saw a story that was by miles different, unnerving even, but possible. I saw young people who were preoccupied with sex but also preoccupied with education and careers. It showed them making mistakes but also it showed them trying to make better choices. And for showing this, that sex was not so much the problem as much as poor sexual choices were, for attempting to move the frame of conflicts to a flexible one, the whole positive parenting film show thing became suspect. Our teachers feared we would become confused. And so, the whole film-screening campaign with its preemptive concern for possible life-altering choices was quietly shelved.

If campaigns to improve sexual and reproductive health education has done anything well in the last couple of decades, it is that it has increased the willingness of parents, schools and religious bodies to talk to about sexual and reproductive health. In communities like the one where I grew up, and perhaps communities like it mirrored all through Africa, this is how you mostly learn sex education: from well-meaning people in churches and schools who would designate whole programs to “talk to the young people about sex”, but deliberately neuter or thwart the message in the “best interests” of young people.

Recently, I attended a church program where the guest speaker, a woman from a religious NGO, insisted that “the computer age” was directly responsible for the proliferation of abortions in young girls. And as I sat there listening to her say these things in her confident, measured voice, I was not worried by the certainty of her illogic. It was the readiness, gratitude almost, with which the audience swallowed this rare information that worried me. The nature of information that was disseminated is problematic, perhaps enough to be counter-productive?

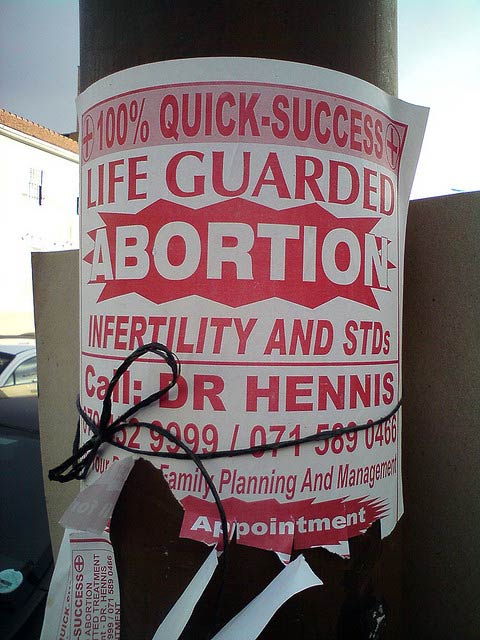

The statistics around abortion appear conflicting. Certain research shows that this conservative approach to sex education led to better sexual behaviour. Other research shows that it did not reduce the abortion rate. And that worse still, the numbers of unsafe abortions in countries like Nigeria are as high as ever. While this says nothing definitive about the challenges that apply to the methods of Sex Education currently practiced in Nigeria and other African countries, enough information exists that draws attention to the inadequacies of the approach.

From school lessons in the 1990s to school lessons now, SEX = SIN is the form of sex education that young people are getting, instead of the more pertinent ‘there are safe ways to have sex’. This is mostly because Nigeria, like much of Africa, is a highly religious space, where your Sunday School teacher most likely doubles as your concerned/willing school teacher, so there is the unavoidable problem of an overlap of the same kinds of sermonised sex education everywhere.

The dangers of going out to seek or buy protection can still seem as big and as real as the dangers of reckless, unsafe sex in certain communities. And this sermonised form of Sex Education which very often equates the emphasising of condom and contraceptive use as promoting irresponsibility, if anything, contributes to the entrenchment of conservative ideas in communities that are already too conservative.

Sex education is everywhere; on billboards, on TV, in churches, in schools, but it is still a long way from being about the simple and most basic thing: the right to protect yourself. It is yet to transcend religion or what I am willing to telling you. It is yet to be about life, about safety, about options.

Kechi Nomu writes from Warri, Nigeria. Her poems have appeared in Saraba Magazine and Brittle Paper.