As several thinkers have said over the past century, a society should be judged by how well it treats its most disadvantaged members. By that count, the world is not faring very well when it comes to education.

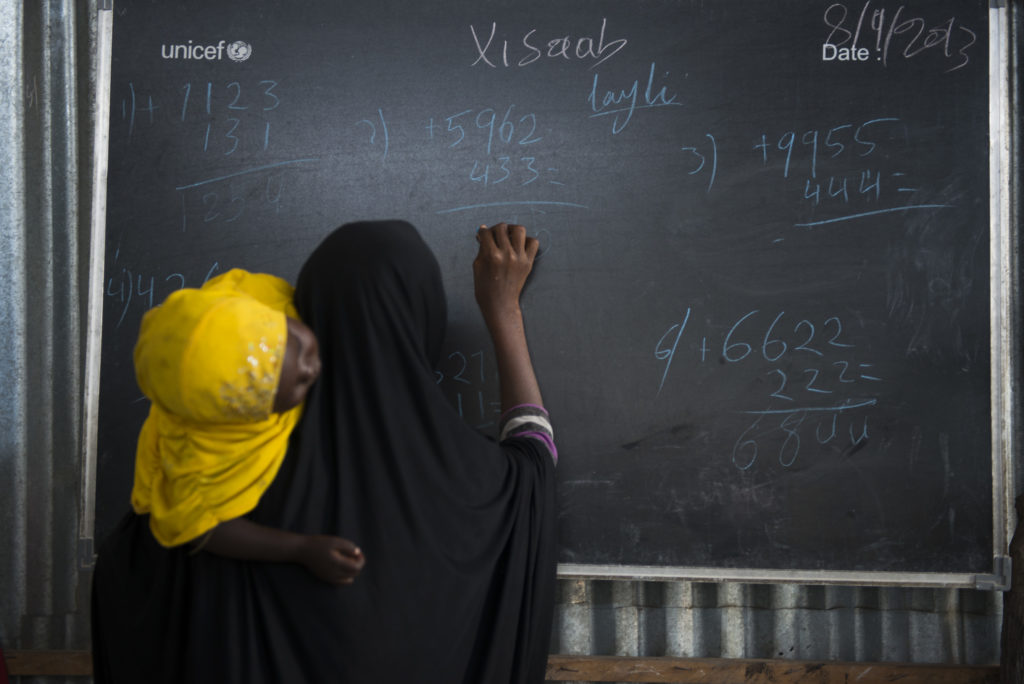

In spite of the laudable progress across the world in getting more children into school, the most marginalised – including girls, children in poor rural areas and the disabled – continue to be systematically left out.

Consider these troubling facts, from the 2013/4 Education for All Global Monitoring Report, Teaching and learning: Achieving quality for all, which launched today in Addis Ababa:

- In low and lower middle income countries, the poorest rural young women have only spent three years on average in school – at least six years less than the richest urban young men.

- In sub-Saharan Africa, at recent rates of progress, all the richest boys will complete primary school by 2021, but the poorest girls will not catch up for at least another 60 years.

- It may take until 2072 for all poorest young women to become literate in low and lower middle income countries.

- About 90% of children with disabilities in Africa are out of school.

The global picture is even more stark: 250 million primary school age children are not learning the basics, whether they are in school or not – and a majority of them are children who face marginalisation or discrimination.

These numbers should not only prick our collective conscience but also galvanise us to act – and act quickly. It is fair to say that the main reason we are 57 million children off-target to reach the second Millennium Development Goal (MDG) – to get every child in school – is because we have not paid attention to the most marginalised and the most vulnerable. We should resolve to do better.

Luckily, we have an opportunity to do just that as we focus on the global development framework that will succeed the MDGs. We have to make it our top priority to end inequalities by meeting the needs of the marginalised.

Young people made that clear during the first “Youth Takeover” of the United Nations General Assembly. On July 12 last year – dubbed Malala Day because it was the 16th birthday of the Pakistani education activist Malala Yousafzai – youth leaders including Malala called for equity to be at the heart of new global education goals. We want the post-2015 goals to have clear targets that can be measured using indicators that track the progress of the most disadvantaged.

The 2013/4 EFA Global Monitoring Report reinforces this point, outlining the need for targets should be set to achieve equality, taking into account that characteristics of disadvantage often interact: girls from poor households in rural areas, for example, are usually among the most marginalised. Each goal should be tracked not only overall but also according to the progress of the lowest performing groups in each country to ensure that these groups reach the target by 2030.

One of the report’s findings is that children with disabilities are likely to face the most severe discrimination and exclusion, which often keep them out of school. It is urgent to collect better data on children with different types and severity of impairments so that policy-makers can be held accountable for making sure these children’s right to education is respected.

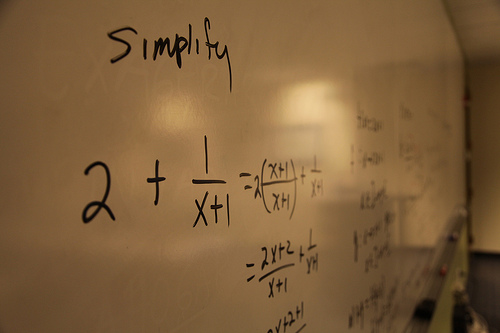

And it is not enough just to get marginalised children into school – they also need to be actually learning once they are there. But they tend to get the worst deal when it comes to education quality, often being taught by the least-trained teachers. The EFA Global Monitoring Report’s main theme this year is the need to meet their needs by recruiting teachers from diverse backgrounds, training them to help disadvantaged children, and giving the best teachers incentives to teach in difficult areas and to remain in the profession.

In a special section, the new EFA Global Monitoring Report also lays out the wealth of evidence for education’s unique power to transform lives. Education boosts people’s chances of escaping poverty, of leading a healthier life and of getting a good job.

I can attest to this. I grew up in a poor, war-torn country, Sierra Leone. Despite overcrowded classrooms and the challenges of being a refugee, I have been lucky to be among the few that have managed to get a good education. That education has not only unlocked many opportunities for me and my family but has also equipped me to contribute positively to the betterment of my society.

Too many of my friends and others in similar circumstances have been denied the boost that education affords, however. It is is doubly unjust that the marginalised, who most need such a boost, are so often bypassed by efforts to improve education.

In 2014, it is not acceptable for any child or adolescent to remain out of school, or to be getting such low-quality education that they aren’t learning. Neither should we tolerate a situation in which so many young people lack the skills they need to get decent work and lead fulfilling lives. Across all our post-2015 global education goals, we should aim for no one to be left behind by 2030.

Chernor Bah is a youth advocate and former refugee from Sierra Leone. Following years of civil war in his country, he founded and led the Children’s Forum Network, Sierra Leone’s children parliament. In that role, Chernor presented a report on the experience of Sierra Leonean children to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In 2002, Chernor served as Junior Executive Producer of a UN Children/youth radio project, designed to involve young people in Sierra Leone’s post conflict discourse. Since then Chernor has worked with youth in Liberia, Lebanon, Haiti, Philippines and other emergency settings, leading efforts to strengthen youth voices in development and policy processes. A former UNFPA Special Youth Fellow, Chernor co-wrote a report titled “Will You Listen-Young Voices from Conflict Zones” and co-led the Youth Zones initiative. He holds an MA in Peace Studies from the University of Notre Dame and a Bachelor’s degree from the University of Sierra Leone.