I’ve been pondering about the origin and meaning of the two terms, Botswanan and Batswana. How nationals in African countries self-identify and how they identify their fellow citizens can tell us a lot about the level of inclusiveness and nationalism in a country.

According to Oxford and Merriam-Webster dictionaries, the correct English term for nationals from Botswana is Botswanan. Therefore, it’s the preferred term by editors and writers worldwide. The majority of nationals from Botswana prefer the use of the complicated term Batswana. The addition of “Ba” meaning “the people of”, seemingly implies that everyone in Bostwana is Tswana. This makes it a term loaded with problematic histories of colonialism, exclusion and ethnic relations.

Who then, is Botswanan?

Botswana’s political borders were formed under colonial rule, bringing together diverse ethnic groups who comprised Bechuanaland. It was renamed Botswana in 1966 when the country gained independence from Britain. Today, it continues to be a multi-ethnic society.

Its main ethnic groups include the Tswana, Kalanga, Batswapong, Babirwa, Basarwa, Bayei, Hambukushu, Basubia, Baherero and Bakgalagadi people. In addition, there are other minority groups including whites, Indians and immigrants from other African nations.

Colloquially, all these ethnic groups are referred to as Batswana. However, applying the term Batswana to them is misleading.

Who then, is Tswana?

Nearly four million people who identify as Tswana live in southern Africa – one million in Botswana and three million in South Africa. It is used to describe the North Sotho, West Sotho, Sotho, and Pedi ethnic groups who have a similar culture and speak the same language.

The West Sotho Tswanas live in Botswana. They consist of eight ethnic groups and together make up a sizeable amount of the inhabitants, comprising roughly 70% of the population.

Due to their numbers, Tswana language and culture dominates mainstream Botswanan society. They have a distinct culture that is different from the other ethnic groups living in Botswana in terms of social organisations, ceremonies, language and religious beliefs. Therefore, a unifying Tswana culture that distinguishes them exists. Culturally, they are arguably more similar to the Pedi and Sotho in South Africa then they are to some ethnic groups within Botswana. Therefore, the term Batswana can be seen as a reflection of the presence of a dominant Tswana culture in Botswana and not a reflection of the multi-ethnic society Botswana actually is.

Botswana does not constitute a homogenous nation with a single language or culture. Therefore, the term Batswana should not be an umbrella term for all of the people within Botswana’s borders which include non-Tswana groups who have a different culture and may speak their own language. Additionally, anyone speaking the Setswana language should not be considered Batswana because this dominant language needed to function in contemporary Botswana where 26 languages are spoken. Therefore, an ability to speak a language doesn’t make a person the ethnicity of the people from which that language derived. As an example, the ability of the Khoi-San to speak Setswana does not technically make them West Sotho nor Batswana.

Who then, is Basarwa?

The Basarwa, who are commonly known as the Khoi-San or “Bushmen”, are often lumped in to this broad category of Batswana. They are made up of Khoi and San people who are further divided into distinct groups with their own languages and culture. They have long resisted being labelled terms such as “Bushman” and even “Khoi-San”. Calling them Batswana would just be the latest name to be forced on a group that has struggled to maintain their identity and culture.

Their identification has always been problematic. They are thought to be the “original” people of Botswana. The government does not award them (nor any other ethnic group) “indigenous” status though – they maintain that all citizens of the country are indigenous in order to promote a sense of “sameness”. In part, this is an attempt by the government to incorporate them in the dominant culture by promoting a strong sense of national identity and “developing” them to fit in with Batswana people who are considered “modern”. By labelling them Batswana they are forced to identify as such or risk being labelled as “backward” or otherwise “othered”, which marginalises them. In part, it is also an attempt at controlling their resources, culture and land – for tourism and diamonds – under the pretext of homogeneity or “oneness”.

Given the aforementioned relations between the Baswara and the Tswana-speaking groups, calling them “Batswana” when they feel their culture is threatened by them is problematic.

Similarly, other groups in Botswana may feel similar offense when being called Tswana for much less severe reasons such as simply not being Tswana.

Who then, is Batswana?

Simply speaking, the term Batswana is problematic for those ethnic groups such as the Khoi-San with their own cultural, linguistic and genealogical identities.

Botswanans need to be more conscious when they identify everyone from Botswana as Batswana in order to be more inclusive of the minority groups. Such a loose term which is meant to unify people can have the opposite effect by further marginalising minority ethnicities.

Next time someone problematises my use of the term Botswanan, my simple response will be, “What then, are the Basarwa?”

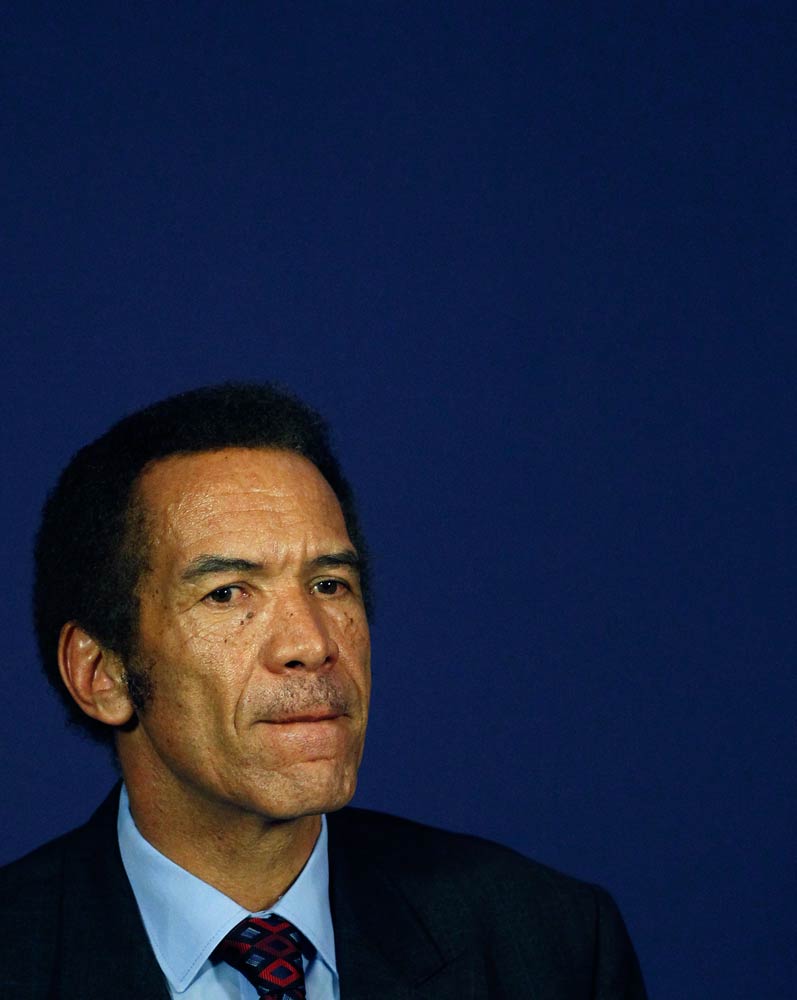

Sitinga Kachipande is a blogger and PhD student in Sociology at Virginia Tech with an African Studies concentration. Her research interests include tourism, development, global political economy, women’s studies, identity and representation. Follow her on Twitter: @MsTingaK