Friday 4 July: Independence Day. There will be speeches, celebrations and fireworks. But these celebrations will be taking place on the other side of the world from the US, because on Friday, the central African country of Rwanda will mark its own Liberation Day.

It is 20 years since the end of the genocide that saw the deaths of more than 800 000 people. Since 1994, Rwanda has worked hard to create a peaceful state and among those enjoying the fireworks will be female parliamentarians from around the world, who are meeting in Rwanda this week to discuss how to get more women into every country’s Parliament.

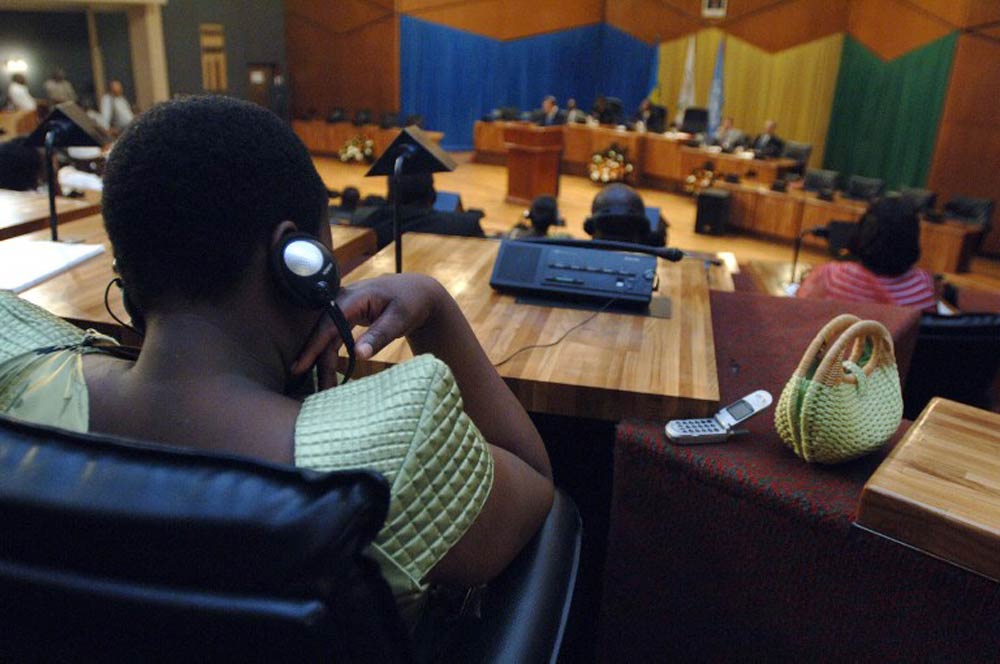

For this is Rwanda’s big success story. It has the distinction of being the only country in the world with more female MPs than male ones, a statistic that has attracted a good deal of international attention, not least from the Zurich-based Women in Parliaments organisation, set up last year, which this week is holding its summer summit in the Rwandan capital, Kigali.

Not surprisingly, many of those attending the conference are keen to find out how Rwanda has managed to reach the figure of 64% women in its Parliament, which is unheard-of everywhere else. Worldwide, women still represent under a quarter (21.9%) of all elected parliamentary seats, but in Rwanda the post-genocide situation, in which 70% of the country’s remaining population was female, and the introduction of quotas requiring 30% of political and government candidates to be women, have brought about real change, in national and local politics and across public positions. Half the country’s 14 supreme court justices are women, for instance. Boys and girls now attend compulsory primary and secondary school in equal numbers, and new laws enable women to own and inherit property.

But this is not just about numbers. The rebuilding of Rwanda’s public bodies was driven by a number of senior women determined that women’s gains in senior positions would not be lost as the gender balance gradually began to adjust. They include Donatille Mukabalisa, the speaker of the Rwandan chamber of deputies, who has been pushing reform over the past two decades. Mukabalisa, whose keynote speech opened the conference on Tuesday, has said that while the quota system clearly helped speed up women’s participation in politics, women appointed and elected to a whole range of public positions have been so successful in making a positive difference that the country may reach a point where quotas are unnecessary.

There are other lessons to be learned from the country’s rebuilding process. One of those is about handling disputes, and the need to increase the participation of women in post-conflict societies.

The middle day of the conference has been set aside for field trips, to see more about the real lives of women other than society’s leaders. It’s an astute move, for behind the headlines is anxiety about the reality of life for ordinary women in the country. One Rwandan women’s rights campaigner has described the female parliamentarians in Rwanda as like a “lovely vase of flowers in a living room” – decorative but not a huge amount of use.

There are concerns about violence: the government’s own figures from 2010 show that two in five women reported suffering physical violence at least once since the age of 15. And many public services in the country are sparse. Rwanda’s first state speech and language therapy service was set up only this year at the Rwanda Military Hospital, with support from a volunteer UK speech and language therapist.

But Rwanda certainly provides a useful lesson for UK politicians. The Conservative party, which has failed to increase the number of female MPs in the party from a dismal 16%, is now seriously considering all-women shortlists. The Liberal Democrats, with an even worse figure of just 13% female MPs, and even the Labour party, with 33% female MPs, might also want to take note.

• Jane Dudman is chairing a session on the impact of female parliamentarians on the UN’s post-2015 millennium development goals at the Women in Parliaments’ summer summit in Kigali.