Balcad is the hometown of my father, his father, his father’s father (you can see where I am going with this). It’s about an hour’s ride to Mogadishu depending on what kind of bullshit you have to encounter to get there on that particular day. My dad complained how back in the day the trip took only 30 minutes and provided a great source of daily entertainment, gossip and scandal. Balcad is a farming and agricultural town, where goats compete with humans for control of the road. Men and women wake up at the crack of dawn and spend hours sitting by the main road drinking copious amounts of tea and arguing about absolutely nothing. One of most powerful people in the town is the humble bus driver who we rely on for our movement in and out of Balcad.

I had previously only made quick visits to Balcad (the last time was in 2004-2005) but this time I was staying for a few weeks, in the same house my parents married in and my siblings were born in. There is something quite peculiar about sleeping in the room in which your parents promised to spend the rest of their lives with each other over two decades ago.

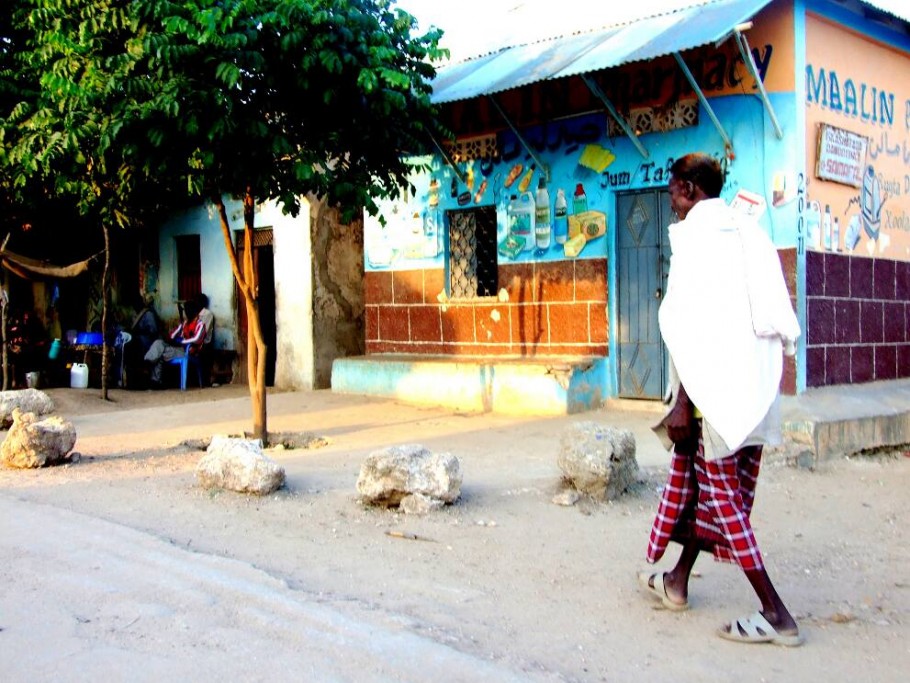

I arrived in Balcad in the heat, bothered by dust and sand clouds hitting me in the eye. From the moment I stepped out of the car, I could feel people’s eyes on me. Their stares followed me as I surveyed the main road, the shops, the women who all wore full jalabeebs or burkas. It was as if ‘outsider’ was printed in bold font on my forehead. Thankfully my first visit to Somalia in 2004 had already prepared me for this.

The stares were most intense on the bus rides from Balcad to Mogadishu. The bus never left on time. The driver would sit outside, leisurely drinking his tea, waiting for the bus to fill up with passengers. I’d be sitting in my seat, open to the various curious looks and questions by fellow passengers. It didn’t matter how I dressed, they could always identify me as the outsider. Sometimes they didn’t even ask me anything; they were content to sit and discuss me loudly. During my stay I managed to perfect a blank expression mingled with confusion. It usually saved me from further questioning.

I spent my days in Balcad watching Somali music videos and a lot of badly dubbed Bollywood films. One night the entire road seemed to be in my room: their electricity connection had failed them and the thought of missing their Turkish soap opera was unbearable. Friday soccer games would see half of the town trickle into the green grounds to watch various teams compete against each other. The animosity towards the Mogadishu teams was fantastic!

Some days my dad took me on walking tours, pointing out the ruins of his childhood. I could sense his bewilderment and confusion at times when buildings that used to stand large and proud now appeared before him bullet-ridden. Balcad felt more freeing than Mogadishu, with local residents staying outside till late at night. Residents walked around freely and generally the atmosphere was less anxious than it was during my previous visit.

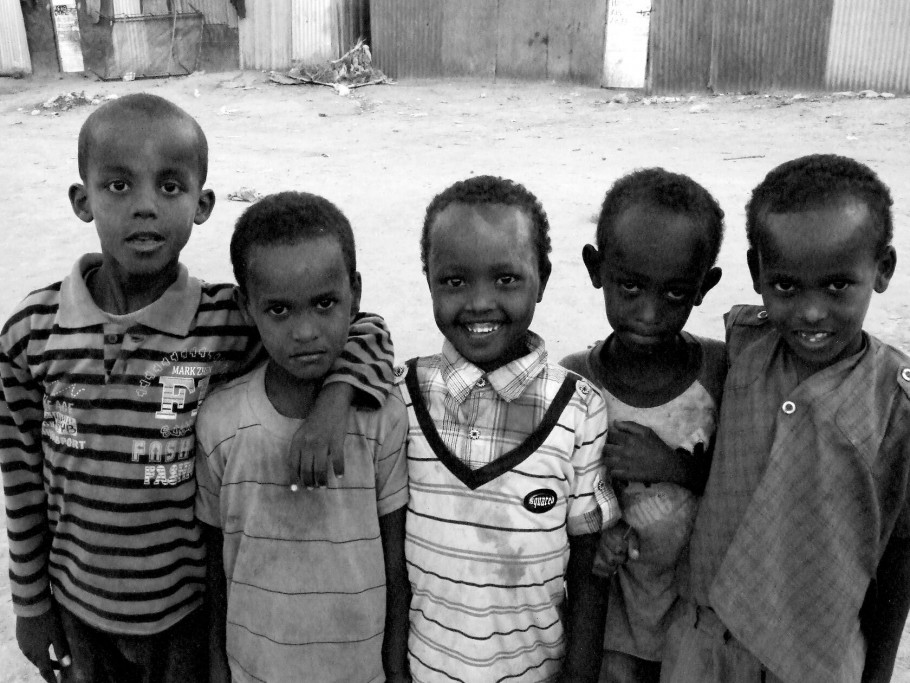

On other days, my grandfather’s housemaid would chaperone me despite my loud and angry outbursts that I was perfectly capable of roaming around by myself. She was a decade younger than me and refused to leave my side while I explored Balcad. Young children would run and scream at the sight of my camera before cheekily returning and asking to have their photo taken. I’d often spend a good 20 minutes taking personal photographs for people.

In Balcad, my grandpa’s town, I was merely my grandpa’s blood. People referred to and introduced me by his name, wherever I went his reputation and presence followed. It was nice. Even though my grandfather is in his eighties, he still treks by foot to his farm each morning to check on his crops, his animals and to basically get away from it all. I did not know grandparents while growing up. My maternal grandfather died shortly before my arrival in Somalia years ago. My paternal grandmother died decades ago. I’m fully realising how limited my opportunities are to understand my grandparents and their stories. Time is definitely never on our side. Hopefully through the stories and photos of my visit, I will have something of them to hold on to.

This post is part of a series by Samira Farah about her recent visit to Somalia. She is a freelance writer and events organiser based in Sydney, Australia. Visit her blog at brazzavillecreative.com and connect with her on Twitter.