There is a proverb in Timbuktu, the legendary medieval city in Mali’s desert, that says: “The ink of a scholar is more precious than the blood of a martyr.”

What Ahmed Baba, the 16th-century intellectual who said it, would make of recent developments is hard to imagine. At the multimillion-dollar Timbuktu institute bearing his name, fragments of ancient texts litter the corridors. The charred remains of not just scholarly ink, but the antique leather-bound covers that protected them against the harsh desert elements are blown by the hot Saharan wind.

During the last days of the Islamist occupation of northern Mali, the al-Qaeda-linked groups who seized control of the territory for almost nine months turned on the Ahmed Baba Institute. In what many people believe was a final act of revenge, and a senseless crime against some of Islam’s greatest treasures, they set the manuscripts alight.

“When the French started bombing, [the Islamists] set the manuscripts on fire as they were leaving,” said Abdoulaye Cissé, interim director of the institute. “Even after most had fled the town, a small group of jihadists returned to make sure that the fire was still burning.”

“We are all Muslims, and in Timbuktu our practical version of Islam has existed for centuries,” added Cissé, a native of the city who remained there throughout the occupation.

“But they practise an archaic Islam and do not consider these writings as the authentic Qur’an because they cover not only religion but science, astronomy, history and literature. That’s their ideology and we don’t support it.”

Cissé, who wears a distinctive silver ring engraved with an Islamic blessing that he had to remove under Islamist rule, foresaw that Timbuktu’s occupiers could target his precious charge. He and colleagues in Bamako, along with guards at the institute, the nightwatchman and his son, and numerous co-operative drivers and boatmen, worked for months by night, carefully packing most of the institute’s 45 000 manuscripts and ferreting them away by road or pirogue boat to the capital in the south.

“It was a dangerous thing to do, we would have been punished if we had been caught,” said Cissé.

“But people really came together to help us. Every time we told them what they were carrying, they all kept it secret and kept them hidden until they left the occupied area.

- Read the fascinating account of how Cissé and his colleagues saved the manuscripts here.

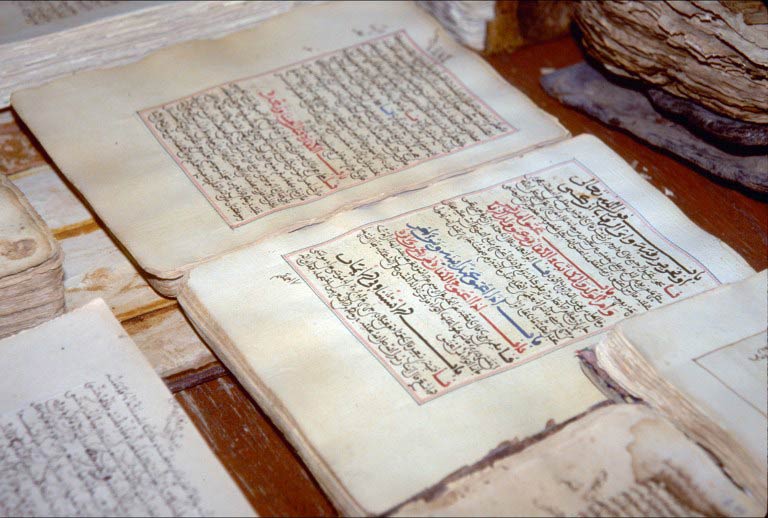

These ancient manuscripts, which could number up to 400 000 across the region, are a source of pride in Mali – and across sub-Saharan Africa. As Africa gained independence from European colonial powers, the texts – the oldest of which date from the ninth century – became a means for the pan-African movement to refute racist notions of a primitive, unlettered continent with no written history.

“People think that African history is oral, that the blacks were not writing until the white man arrived in Africa,” said Cissé. “But we know written literature. That is our mission – to one day recreate the history of Africa through the knowledge contained in those manuscripts.”

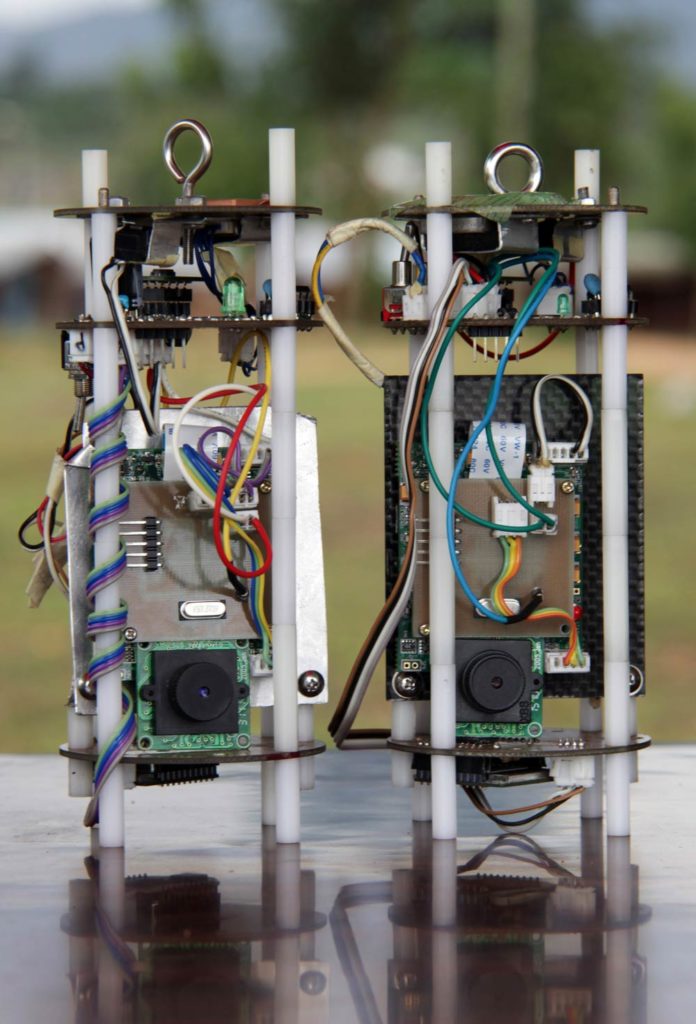

Timbuktu, which is now a Unesco world heritage site, was founded in about AD1103 and flourished as a commercial hub of the caravan trade between black Africa and the Maghreb, Mediterranean and Middle East. The Ahmed Baba Institute, opened with much fanfare by the former South African president Thabo Mbeki in 2009, has just received about £65 000 in funding from Saudi Arabia to digitise its manuscripts.

“We want to digitally secure all the manuscripts before they are brought back to Timbuktu,” said Cissé. “But then they must be brought back. The manuscripts are meaningless if they’re not in Timbuktu.”

An unintended consequence of the Islamist occupation of the city has been a renewed global focus on the priceless manuscripts, which although mostly written in Arabic also include centuries-old writings in Greek, Latin, French, English and German.

But while the Ahmed Baba Institute is painstakingly working to preserve preserving this history, other manuscripts in Timbuktu are faring less well.

In a narrow, sandy street in the central Badjinde quarter, Kunta Sidi Bouya climbs a steep flight of cracked, mud-cement stairs to a special prayer room on his roof. He lifts half a dozen worn, fraying books from a shelf in the corner, bound exquisitely in antique and decaying leather, and lays them out on the rug on the floor.

Bouya’s home contains one of Timbuktu’s thousands of private manuscript collections, texts written by the family’s ancestors and handed down through the generations.

“My ancestor, Sheikh Sidi al-Bekaye, was a scholar who lived hundreds of years ago, he wrote these,” Bouya said proudly. “It feels special when you read something your own grandfathers have written. These are part of our family and they are private.

“You are only allowed to handle them when you have attained a certain level of Qur’anic education. Being able to read Arabic is not enough – you have to learn to understand them completely.”

Bouya (35) a teacher at a Qur’anic school in Timbuktu, said he feared for the safety of his family’s manuscripts during the occupation.

“The jihadists attacked and destroyed the shrine to one of my ancestors and we feared they would come for the manuscripts,” he said. “But in the end they never came door to door looking for them.”

Life was complicated under Islamist rule, Bouya said, and they were happy when the French liberated the town. But now his manuscripts face another, older challenge.

“We fear for their survival. They are old and they are suffering from the elements here,” Bouya admitted. “We try to touch them as little as possible and when people come here asking to see them to do research, we hide them to protect them.”

Unesco said the plethora of private family manuscripts posed a huge challenge to efforts to conserve Mali’s cultural heritage.

“Something has gone wrong with Mali’s documentary heritage,” said David Stehl of Unesco. “There have been various programmes for their conservation but they have not created the conditions to adequately protect the manuscripts. They have lacked transparency and co-ordination.

“Even the legal question of who owns these private manuscripts is unclear. You have hundreds and thousands of them right across Mali and they are very much tied to families and private owners. We are concerned about the degree to which they were handled during the Islamist occupation – people started touching them, dispersing them and, especially for those that were moved to Bamako, they’ve now been exposed to completely different climatic conditions.

“Something has to be done to protect these collections, but it is a huge task – monstrous actually.”

Preserving the manuscripts is crucial, experts in Mali say, not just to learn about the past, but also the future.

“We have not even begun to exploit the knowledge included in these manuscripts,” said Cissé.

“Translation is not enough – we need specialists to analyse and interpret them. They are full of parables, hidden messages, images – all of which take specialists to understand. Only then can we understand the practical value of this wisdom that was written down hundreds of years ago.”

Afua Hirsch for the Guardian.