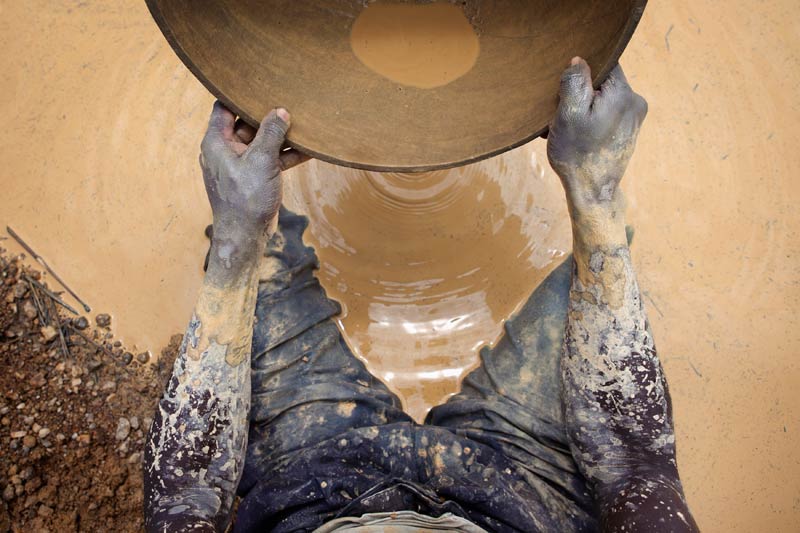

The face of Lydia Madhoro (25) is dusted red from soil as she and her three female colleagues take a brief lunch break. They have been working since dawn on their gold mine in Zimbabwe’s Mashonaland Central Province.

Their hand-dug shaft has reached about 10m in depth, and their conversation revolves around estimates of how much they will make from a pile of gold-bearing excavated rocks. The ore still has to be taken to a miller about 15km away to be crushed, after which it will be mixed with water and mercury to separate out the gold.

Truck operators who transport the ore charge them US$50 a ton, and casual labour used for the loading demand $10 for the same quantity. The millers charge a fifth of the gold obtained.

“We are at work almost every day of the week, going underground for the ore. This is extremely hard work that has been associated with men for a long time, but we are now used to it. We have to do it because, as single mothers, we must feed our families,” Madhoro told IRIN.

The four women formed a syndicate in 2011 to acquire their 0.8-hectare claim near Mazowe, about 50km northeast of the capital, Harare. Madhoro and her partners are certified gold miners and sellers from the mining town of Bindura, about 40km away. They paid about US$1 200 for the registration, prospecting licences from local administrators and surveyor’s fees.

In a good month, they make as much as $2 500 from the mineral, which they sell to the government-owned Fidelity Printers at $50 a gram. The money is divided among the partners in equal shares after paying the millers’ fees and transport costs; the proceeds have so far been used to build basic housing.

“Even though we are not yet making that much money, the good thing is that we have stood up as women to fend for ourselves. We are actually doing better than some men, and I am proud of the fact that I single-handedly feed my twin daughters and can afford money for their primary education, clothes and other basic needs,” Madhoro said.

Breaking barriers

Zimbabwe’s economic malaise, now more than a decade old, is seeing women take on work that has traditionally been deemed the domain of men. Madhoro and her colleagues’ mining enterprise is far from unique, she says. She is aware of numerous women-owned and operated mining syndicates in the province, in districts like Bindura, Shamva and Madziwa.

Eveline Musharu, president of the 50 000-strong NGO Women in Mining, which helps women start mining ventures, told IRIN: “Women are breaking the barriers by venturing into mining, an industry that is dominated by men. There are tangible gains for women who have joined the sector as small-scale miners, especially in gold and chrome, as they can afford household nutritional needs, pay school and medical fees, and even afford some modest luxuries.”

The national NGO was established in 2003, and its members are mainly drawn from the ranks of the rural poor, the disabled, widows, single mothers and those living with HIV and Aids. Musharu said women are turning to mining as an economic lifeline because, given the vagaries of the climate, subsistence farming is no longer a guarantee of putting food on the table.

Madhoro’s route to mining began when she became pregnant by a teacher, dropped out of school and gave birth to twins. Her parents disowned her, and she went to live with her grandmother. When her children were six months old, she became an illegal miner. One night, after digging for gold along the Mazowe River, she was nearly raped by a group of other illegal miners; after that, she tried to make a living as a hawker. Then she learned about Women in Mining.

When she approached the NGO for advice on how to enter the mining sector, the organization suggested she form a women’s syndicate before applying for a prospecting licence. She chose her three partners because they were already friends and stayed in the same suburb in Bindura.

Boosting incomes

The six-year-old Zimbabwe Women Rural Development Trust (ZWRDT), which has more than 500 members and operates mainly in the Midlands and Matabeleland provinces, also helps women get a foothold in the mining sector. More than 100 members of the organization are miners.

ZWRDT director Sarudzai Washaya said 35 of the members, all of whom had previously worked as illegal miners, had been coached to enter the sector legally, and have seen their incomes grow as a result. According to Washaya, mining legally has several advantages, including eliminating the risk of being arrested and having one’s minerals confiscated. Legal miners are also guaranteed of a formal market where they are safe from thieves.

“There is a lot of keenness on the part of rural women to get into mining as they realize the opportunities that the sector offers. Chiefs and district administrators help our members identify and obtain mining claims, and ZWRDT facilitates the acquisition of prospecting licences, and prospective miners pay a joining fee of $20,” Washaya told IRIN.

“We have realized that it is important to build confidence in women, [showing them] that they can perform just as well as, if not better than, the men who dominate the mining sector. In some cases, the women are now employing men, and a few have even managed to buy luxury cars,” she said.

Capital often out of reach

Accessing capital for mining ventures remains one the biggest obstacles for women. Mining equipment, such as compressors for milling ore and pumps to drain water from mine shafts, are generally unaffordable, and women miners have to resort to renting equipment at high costs, eroding their profit margins.

Virginia Muwanigwa of the Women’s Coalition in Zimbabwe, a national NGO for the advancement of women, told IRIN: “Because our society is dominated by men, it is difficult for women to produce collateral when approaching banks. They don’t have title deeds to land, especially in rural areas.”

She said, “If well supported, women can use their involvement in mining to fight the many livelihood vulnerabilities they face. Women miners can benefit a lot from a revolving fund that the government and donors can help establish and from which they can borrow, as banks are unwilling to lend them money.”

The lack of equipment makes mining an even more arduous occupation. “Some of the women have given up on mining because of its high demands and gone back to face poverty in the villages. There is need for the government to give us support because, currently, we are struggling to sustain ourselves in mining,” Washaya said.