A lot is made in South Africa of the “refugee situation”; that is, desperate immigrants from other African countries who have chosen to settle in the continent’s southernmost country.

Protestations that Nigerians, Congolese, Malawians and Somalis, in particular, “have come to steal our jobs” are as ubiquitous as the daily furore at the taxi rank over who saw which customer first.

That is complete nonsense of course, and everyone knows it, but it is one of those topics, like dissecting the merits of the Pep Store funeral plan, that locals like to debate endlessly.

Yet in truth South Africans are among the greatest number of refugees going around, so to speak.

Ask any South African on the street where they are originally from, and they will invariably tell you a location hundreds of kilometres away from where they live now.

And in Mzansi, there is no greater natural refugee than one who hails from the Eastern Cape. I should know – I am one.

According to the 2011 Census, in the Eastern Cape, 436 466 people left the province since the last census 10 years prior. Ninety-four percent of the Eastern Cape population was born in the province, compared to 56% of Gauteng’s population.

And almost two million people born in the Eastern Cape lived in other provinces, with the majority living in the Western Cape in and around the Cape Town metro (0.9 million) and Gauteng (0.5 million).

Desperately poor under apartheid and equally so now, the Eastern Cape has never quite managed to get off the ground, despite vast swathes of natural beauty, excellent schools and universities and being home to South Africa’s motor industry for decades.

Every year scores of us leave to work in Johannesburg or Cape Town, either in the industrial or mining sector or to pursue a career in the corporate or entertainment field. “That’s where the money is” we are told, and off we go; an annual exodus not seen since the days of the Biblical plagues.

I myself am a late bloomer in terms of the Eastern Cape émigré, having only settled in Cape Town several months ago. Yet, even now, I can honestly say my reason for leaving was neither financially-driven nor born out of any especial desire to become a master of the universe.

Yes, I was in need of a job upon my return from Southeast Asia, but the main catalyst for my decision was that Cape Town – with all its hipsters, beardy-weirdies, flash public-relations types and movie-extra hopefuls – represented the ideal opportunity for change.

I was reared in Port Elizabeth and will always be proud to call it my home town. But in the last few years I had seen it become a microcosm of Johannesburg where a rat race, and indeed, sometimes egotistical mentality had begun to infiltrate every aspect of your working and social life.

The result was that the city once deemed the friendliest in the land had become disconnected from what it once was – sleepy yes, but a good place to relax and enjoy your days in the sun.

I worked briefly in Johannesburg some years back, but after a few weeks the hustle and bustle of a heaving concrete beast became too much. There was no tangible downtime to take your mind off the previous week’s work, and everyone seemed in too much of a hurry to get onto the next thing – and prove the next thing to others.

I understand perfectly that these attitudes sometimes are required in an economic hub, but they are definitely not for everybody. And neither should they be, especially in a city like Port Elizabeth which was historically always a delightful place to live despite being blue-collar.

So Cape Town it was, a 700-odd kilometre trek up the N2 for this particular refugee.

It has been two months now, so what do I have to report?

Without a shadow of a doubt, change has been effected.

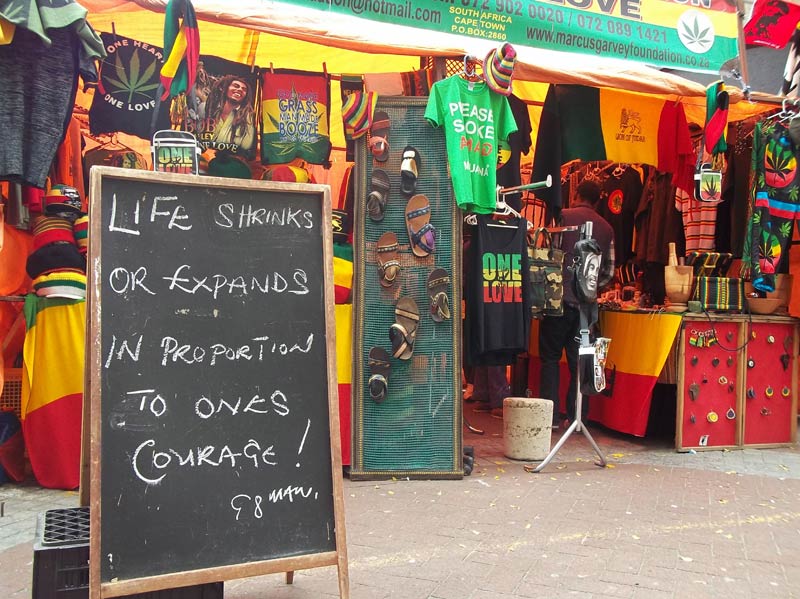

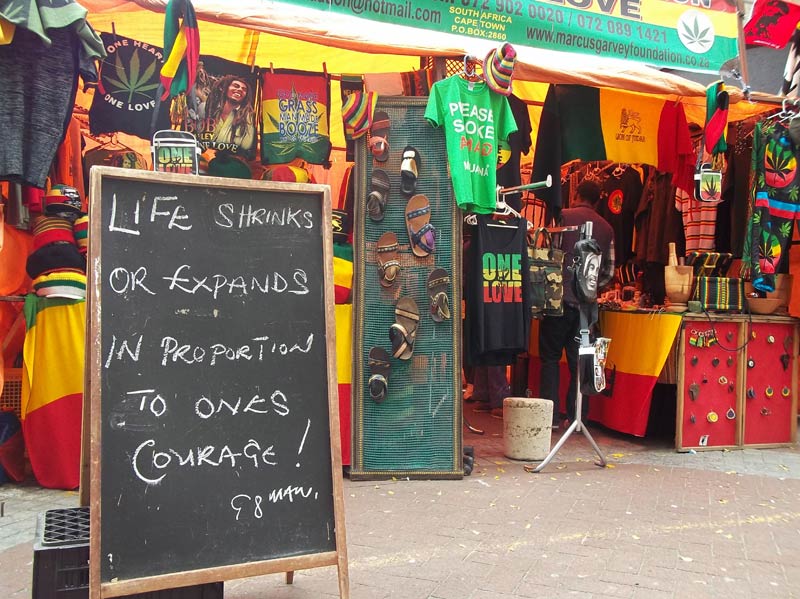

Cape Town, above all, is comfortable with itself, and that is reflected in the attitudes of its residents. Aside from the odd bad apple one encounters, the people are among the friendliest in the country, and that has a marked impact on one’s own attitudes.

The Cape Town native is acutely aware that their city has a reputation for being “cliquey”, but also knows that this arises from a small cross-section of the community who most people avoid at all costs.

Second point: Cape Town residents do not care one jot for the political wrangling that consumes South Africans in other parts of the country.

Contrary to what some might believe, Mother City residents are not in the least bit interested in spending their dinner times dissecting the latest political diatribe from one or other party leader. While they are immensely proud that their city houses the country’s Parliament, one suspects they are even more pleased that the magnificent building bolsters the central business district’s prime real estate value.

It is almost as though politicians are only rolled out when there is an election, otherwise civil society pretty much runs itself.

To be free of South Africa’s great political preoccupation is a huge relief, and it is little wonder that many Capetonians appear perplexed when they see someone ranting and raving about something or other on television.

And finally, how could anyone continue to harbour feelings of anxiety or anger or concern when in every direction there is either a mountain, ocean or vineyard to gaze upon? It is almost impossible to worry about anything for too long.

As South Africans will have guessed by now, the description of myself as a “refugee” in this piece relates to an incident in early 2012 when Western Cape Premier Helen Zille referred to Eastern Cape pupils flocking to Cape Town for improved education as “education refugees”.

It sparked a massive outcry, prompting the ruling party and others to label the Western Cape government an “erstwhile apartheid” regime.

Personally, looking back on that incident now and as an Eastern Cape refugee myself, I don’t see what all the fuss was about.

John Harvey is a media relations consultant in Cape Town. He previously worked as a journalist in Port Elizabeth, Plettenberg Bay and Cambodia, contributing to a number of South African and international publications. He is hoping to obtain his work visa for Cape Town shortly.