Admiring paintings or photographs by Africa’s greatest contemporary artists is a luxury in Benin, where museums are scarce and most people lack money to travel farther afield.

But a new application developed by a foundation based in Cotonou, the largest city in this West African state, is seeking to bring art to the masses by allowing anyone with access to a printer and smartphone or tablet to turn their place into a museum.

“For 10 years, the Zinsou Foundation has been striving to bring contemporary art to people who don’t have access to it because we think culture is a right, not a luxury,” said Marie-Cecile Zinsou, the Franco-Beninese head of the foundation that created the “Wakpon” app.

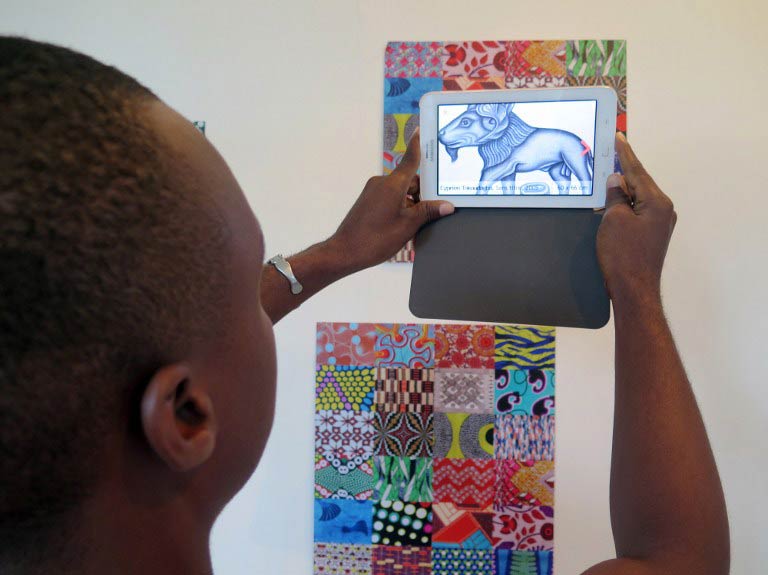

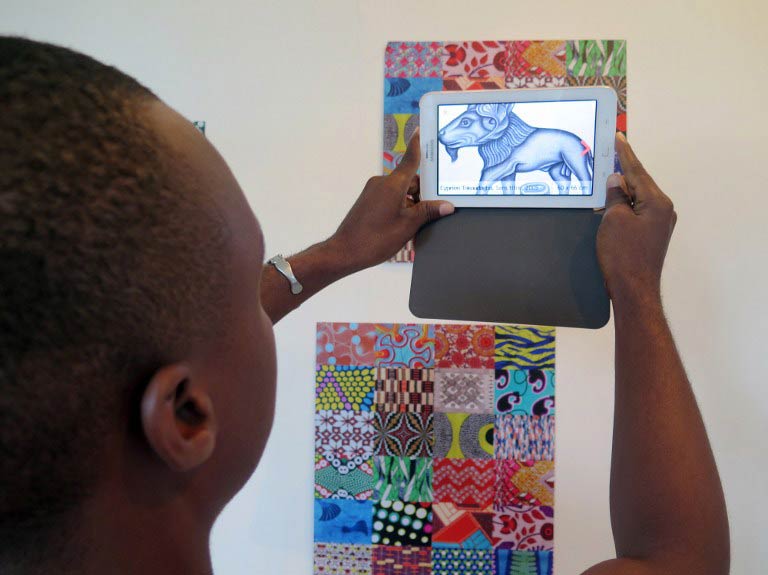

Budding art enthusiasts need only print out colourful images available on the app’s website onto pieces of A4 paper and hang them on the walls of their home, school or government building – just like paintings in a museum.

Visitors can then aim at these images with their smartphones or tablets using the app, and a painting by Benin’s voodoo artist Cyprien Tokoudagba or a photo of Nigerian hairstyles by J.D. Okhai Ojeikere will pop up, alongside information on the work of art.

All in all, 44 pieces by 10 artists are available on the app, all taken from the foundation’s collection.

Low visibility for African art

Zinsou said she convinced her father, who has just been named Benin prime minister, to set up the foundation after she realised that like many other African countries, there were no museums in Benin to showcase the continent’s contemporary art, despite its growing popularity elsewhere.

Leading African artists were virtually absent from art sales just a decade ago but now contemporary works feature strongly in several international auction houses.

Bonhams in London recently described the continent as “one of our hottest properties on the art block”.

Since 2005, the foundation’s show room in Cotonou puts on free exhibitions of Beninese and foreign artists, and once showcased US legend Jean-Michel Basquiat – a first in Africa.

In 2013, it opened a museum in an old building of the former slave trade hub of Ouidah, some 40 kilometres away from Cotonou.

All in all, nearly five million people have visited both places in a decade – most of them them children who often come the first time with their schools, return on their own and then bring their families.

Zinsou said the Wakpon app – which once downloaded does not need to be connected to the Internet – aims to widen access to a broader population.

‘Tomorrow’s museum’

Mobile phone penetration has been low in Benin, particularly for smartphones, because of poor infrastructure.

But competition from international mobile operators and under-sea cables is increasing take-up, as prices come down for both handsets and Internet services.

“This application is amazing,” said Beninese artist Romuald Hazoume, whose work has been showcased abroad and is also available on the app.

“African people will be able to have access to their culture, to their artists who are known around the world but whom they cannot see due to a lack of exhibition sites, of money or visas.

“It’s like a bait. People will know works of art, their story, and they will want to see them for real. It’s tomorrow’s museum and it’s what all big collections should be doing.”

In the Cotonou showroom, those who visit are given a Wakpon demonstration at the end of their tour.

“Wakpon” means “come and see” in Fon, the most widely spoken local language in Benin.

“It’s great. My cousin has a good telephone, I’m going to plead with him to activate the application and our entire district will take a look,” says Obed, 15, who came with his class.

Zinsou said people in Africa had a tendency to think that culture will emerge only once their countries are developed.

“But no, culture is essential for development,” she added.