She is black and trendy, and young South African girls are learning to love her.

Meet Momppy Mpoppy, who is a step ahead of other black dolls across Africa who are often dressed in traditional ethnic clothes.

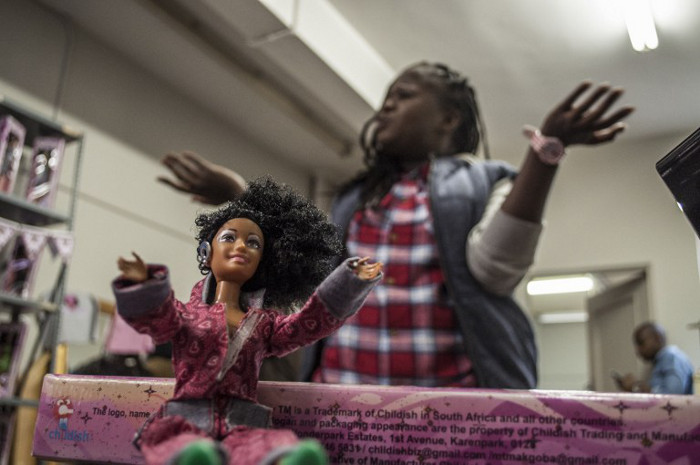

Decked out in the latest fashions and sporting an impressive Afro, complete with a tiara, Momppy could play her own small part in changing the way that black children look at themselves.

Maite Makgoba, founder of Childish Trading and Manufacturing, said she started her small business after realising that black dolls available on the market “did not appeal to children”.

“They were frumpy and unattractive, some in traditional attire. That is not the reality of today,” said the 26-year-old entrepreneur.

The dolls are assembled in China, but the real work starts in Makgoba’s tiny workspace in downtown Johannesburg, where they are styled and packaged before they are sent to independent distributors.

Inside the two-room warehouse, miniature pieces of clothing are sewn and pressed by hand. Appearance is everything.

Eye-catching ballerina skirts, denim pants and “on trend” jumpsuits with bright high heels are some of the items in Momppy Mpoppy’s impressive wardrobe.

Among the different Mpoppy outfits are “Denim Dungaree Delicious”, “Rockstar Tutu”, “Mohawk Fro” and “Seshweshwe Fabolous” — with each doll costing R180 rand.

To complete the experience, the company also makes matching clothes for girls who own the doll.

“This is more than just a business, we are creating awareness, that our dark skin and thick Afro hair are pretty as they are,” said Makgoba.

“We want kids to see beauty in Mpoppy, to see themselves while playing with her.

“Dolls are often white, people in magazines are white, even in a country like South Africa where the majority are black.

“Black children are confronted with growing up in a world that does not represent them, everything is skewed towards whiteness.”

Body image

Makgoba admits that the fledging company which she started in 2013 faces a stiff competition from established toy brands, but she was encouraged by the “overwhelming response” from buyers.

“Parents and children have quickly taken to the doll. But we still need to convince large retailers to sell our brand,” she said, declining to reveal exact sales numbers.

Nokuthula Maseko, a 30-year-old mother of two, said her children had “fallen in love with the unusual doll” after she came across it on social media — the company’s biggest marketing tool.

“I like the fact that the doll looks like my kids, in a world where the standards of beauty are often liked to Caucasian features,” said Maseko.

“The kids love the doll.”

“This is a big social movement … it can help prevent body image insecurity among children,” she added.

But the Johannesburg mother said she was not in a hurry to throw away her kid’s white dolls.

“At school they play with their white friends, so this is my idea of maintaining that realism, so that they are aware of different races and not that everything is just white and only looks a certain way,” she said.

Black dolls are not new, but the African market has for a long time been flooded with white dolls, creating an image of porcelain skin perfection with long shiny tresses.

The iconic 57-year-old Barbie range has dominated global sales, selling over one million a week globally — including a selection of black dolls.

It’s a tough challenge to build a brand name for start-up companies like Makgoba’s and others such as Queen of Africa, a popular black doll from Nigeria who is kitted out in ethnic attire.

According to Johannesburg child psychologist Melita Heyns, toys have a long-term influence on children.

“It’s not just entertainment … dolls are a big part of a girl child’s life, it’s important that such toys help build a child’s character and self-esteem,” said Heyns.

Mpoppy’s creators plan to export to neighbouring African countries, changing young mindsets one doll at a time. – By Sibongile Khumalo