Funerals can be lengthy affairs in western Kenya, and Liz, a 16-year-old schoolgirl, was out late at a wake for her grandfather that had stretched into the evening. She was on her way home when she recognised some familiar and unfriendly faces in the darkness. She knew instantly that the six men in front of her meant her harm. A tall girl, she tried to run. When they caught up with her, she tried to fight. Her attackers, thought to be aged between 16 and 20, began by punching and kicking her. After she was hurt too badly to resist, they took it in turns to rape her. The problem was that the teenager would not submit quietly: she kept screaming.

When they had finished with the girl, they dragged her to a deep pit-latrine nearby and threw her inside. But despite her horrendous injuries and a fall of nearly 3.6 metres, Liz managed to find the earthen steps used by the workers who dug the latrine to get out. As she pulled her broken body up the steps, villagers who had heard her cries found her.

They quickly raised a mob to give chase. The schoolgirl knew some of the men who had raped her and started shouting their names. The villagers managed to find three of Liz’s attackers and frogmarched them to the police outpost in the village of Tingolo, in Kenya’s north-western county of Busia. The officers arrested the trio for assault and promised the girl’s angry neighbours that the men would be punished. At daybreak, the rapists were handed curved machetes, known as “slashers”, and told to cut grass in the police compound. Duly punished, they were sent home.

The morning after the attack, Liz (not her real name) was taken to a dispensary, a rudimentary pharmacy that is the closest much of rural Kenya gets to a clinic, where she was given antibiotics and paracetamol. It was only when she found that she still could not walk, a week later, that her mother sold their chickens – the family’s only source of income – and took her to a medical clinic in the nearest town. The doctor ignored the fact that she was doubly incontinent and told her she needed physiotherapy. Her condition worsened and her mother leased the family’s land for about £60 – effectively mortgaging their home – to get her to the nearest big town, Kakamega, where she was eventually diagnosed with a fistula and damage to her spinal cord.

‘One of many’

This appalling, tragic tale would never have reached the outside world had it not been for the outrage of Jared Momanyi, the director of one of a handful of Kenyan clinics that specialise in the treatment of victims of sexual violence, to which Liz was eventually referred. He called a young reporter at the Daily Nation in the capital, Nairobi, who had previously written a story about the facility in Eldoret, a town perched on the western side of Kenya’s Great Rift Valley. “It troubled me so much I needed to take it head on and tell the world,” he said. “This was an attempted murder and it’s not an isolated case; it’s one among many.”

When the Nation’s Njeri Rugene visited Liz more than three months after the 26 June gang rape, she found a broken, traumatised girl in a wheelchair. The story Rugene wrote helped raise £4,000 to pay for an operation to repair Liz’s internal injuries, the first of two procedures the girl will need to have any chance of controlling her bladder and bowels or walking again.

What has made the teenager’s trauma even worse is that her assailants are still free. “She can’t understand why people keep coming to ask questions but those men don’t get arrested,” said Rugene.

Three of those who raped Liz are pupils at schools near her own and police have had the names of all six attackers since 27 June. After stories appeared in local newspapers, officers were finally sent to arrest those still in school. Teachers at one of the schools asked if the arrests could be postponed to allow them to take part in exams. The request was granted and police claimed afterwards that they were “tricked” by the teachers, who helped the pupils go into hiding.

Mary Mahoka, a social worker with a local child protection organisation, said cases such as Liz’s were the product of entrenched chauvinism in her home area of Busia, an impoverished county close to the shore of Lake Victoria.

Polygamy was widely practised and girls were not valued by the community, she said. When she first started to work with rape victims in 1998, she found that perpetrators would pay for their crime by handing over a goat or a bag of maize to the girl’s parents.

Last week, Mahoka was helping a six-year-old girl who had been sexually assaulted by a man in his 20s. “It’s happening every day, but often it’s not reported,” she said.

Mahoka, whose organisation is partly funded by UK aid, has to disguise the nature of her group’s work, calling it “rural education and economic enhancement” so as not to provoke hostility among traditionalists in the community.

She has investigated the gang rape and says it was not a chance occurrence: “Liz had rejected advances from one of the boys, so he brought his friends to discipline her.”

‘Silent epidemic’

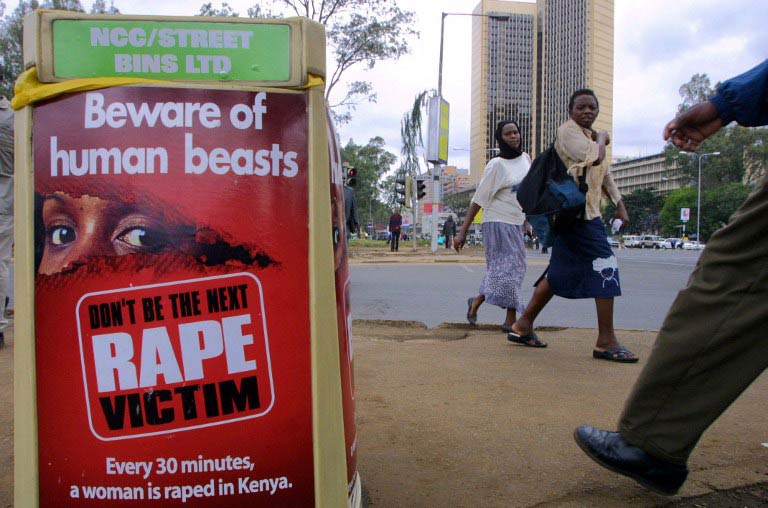

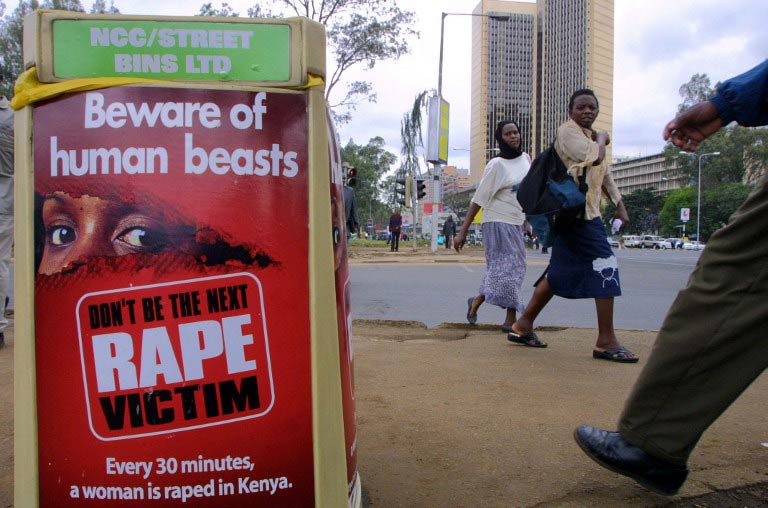

After reading about Liz’s ordeal, Nebila Abdulmelik, a women’s rights activist in Nairobi, launched an online petition with the international campaign group Avaaz that has attracted more than 660 000 signatures. “Letting rapists walk free after making them cut grass has to be the world’s worst punishment for rape,” she said. “There is a silent epidemic in Kenya. It’s not as loud as in Congo or South Africa, but the statistics are high.”

As many as eight out of 10 Kenyan women have experienced physical violence and/or abuse during childhood. A report from Kenya’s national commission on human rights in 2006 found that a girl or woman is raped every 30 minutes.

Orchestrating rape is also among the charges facing Kenya’s president, Uhuru Kenyatta, who goes on trial on 12 November at the international criminal court accused of organising the violence that killed at least 1,300 people after a 2007 disputed election.

Abdulmelik notes that, under Kenya’s Sexual Offences Act, Liz’s assailants should face prison sentences of not less than 15 years. The same legislation stipulates that the expenses incurred by victims of such attacks, including surgery and counselling, should be borne by the state. “This is the government’s responsibility,” she said. “There is impunity from top to bottom, and meanwhile our president takes an entourage to the Hague at taxpayers’ expense.”

Avaaz and the African Women’s Development and Communication Network (Femnet), of which Abdulmelik is a member, plan to picket the ministry of justice and police headquarters in Nairobi on Wednesday, where volunteers will cut the grass in protest at the handling of Liz’s case.

The outcry over the fate of the 16-year-old last week prompted Kenya’s director of public prosecutions, Keriako Tobiko, to order the arrest of the six suspects and promise an inquiry into police failures. However, the investigating officer in Busia, Shadrack Bundi, said he had received no such directive and could not take any further action.

Rasna Warah, a Kenyan commentator, said women were being failed by the country’s leaders, male and female, who often left it to foreign-funded NGOs to raise awareness. “The Busia rape case is symptomatic of our society’s attitudes towards women. Violence against women has become so normalised it almost constitutes a sort of ‘femicide’.

Daniel Howden for the Guardian