The joke in our house goes that my husband drove over 14 500km on a scooter through Africa while I spent that 14 500km telling him how to drive. Not quite true, but not quite false either. There were days when I just sat on the back of our 150cc motorbike, lost somewhere in Zambia or Sudan, without saying a word.

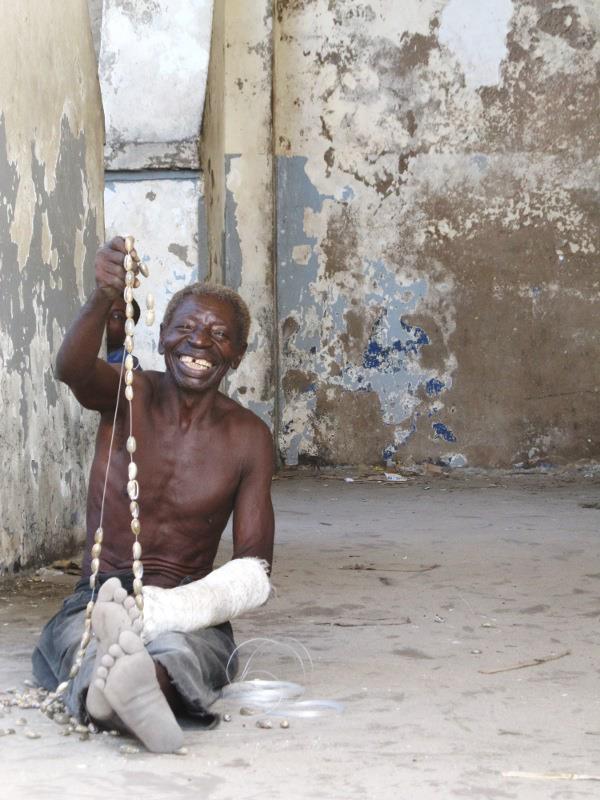

Packing up your life and cutting all the strings that tie you to society is much easier said than done. It is only when you attempt it that you realise just how many things are pinning you down. Banks, cellphones, rent, vehicles, jobs, debit orders, credit cards, medical aid, pensions, doctors and insurance. Everyday things that most of Africa spent their days without. Something we would learn along the way from Pretoria to the pyramids is how little you need to be happy if you just learn to be content. And how, when situations are really bad, the smallest things, can create immense joy. Like an old, dirty bed after sleeping on the floor for weeks on end or a piece of dodgy-looking goat’s meat, served in a dirty plate, after you’ve spent the last 36 hours lost in the desert without food. But I’m jumping the gun here.

Strapped for cash and desperate to explore the rest of our continent, we devised a plan towards the end of 2011. Cash everything in, including our pension funds, savings and most of the money we would have used on our wedding, quit our jobs – I’m a social media manager, Guillaume is an engineer – and travel through Africa. It sounds super romantic, which is probably why we chose to do it for our honeymoon, but let me tell you, there was very little honey during the 153 moons we spent on the road. We could not afford a 4×4 or even just a semi-decent vehicle, which is why we opted for the little motorbike standing in our front yard. It was cheap, it was there and it was absolutely ridiculous – that includes the bright orange coat of paint it was given. But it could average a speed of 75km/h and my husband knew how to drive it so it seemed like a plausible idea. Having finally gotten rid of all those things tying us down, we tied the knot on January 21 2012 during a very small, informal ceremony in the Kruger National Park, packed a single backpack and drove off into the sunset nine days later … aiming “north in general”.

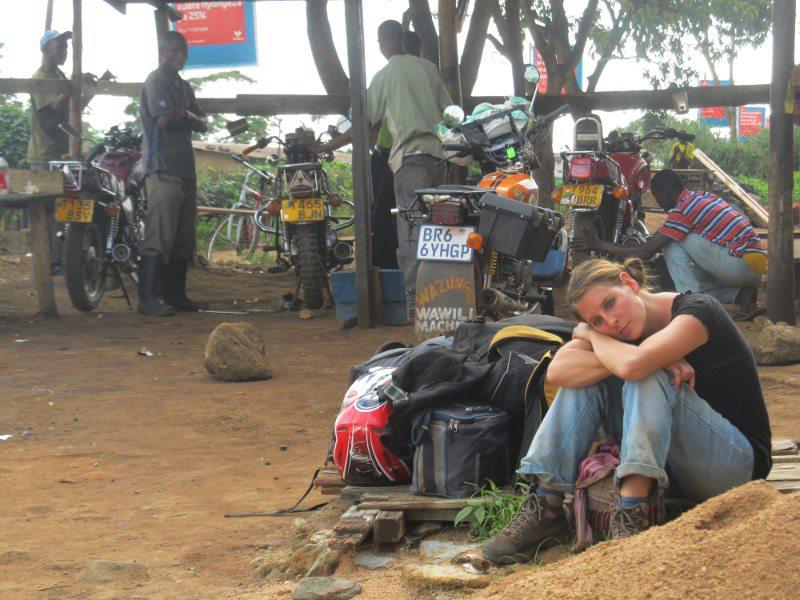

A trans-African journey can be done in one of two ways: with a lot of planning and preparation, or the way we did it – the “fake it till you make it” way. We suggest you opt for the first. We aren’t total fools though and did do some planning. We read a few travel guides, scanned a map, got the necessary visas and learned how to do first aid but apart from that we had only the bare necessities and decided to just “let the journey guide us” – from South Africa through Botswana, the Caprivi strip (now called the Zambezi Region) in Namibia, parts of Zimbabwe, Zambia, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Sudan and eventually Egypt.

In the end, it turned out, it was the locals and not so much the journey that guided us. Without a map we got lost often so we’d find our way from place to place and country to country by asking locals for directions. Things get strange when you stand in front of a Masai warrior next to the ‘highway’ in Tanzania, point in a direction and ask, “Kenya?”. Often we would get to the next town after having “turned left at the big tree on the right before following the long, winding road and after spotting the little house, turned right and drove until we saw town” It was fun, at times.

Most days were tedious. We’d be on a bike from early morning to late afternoon. A bike that broke down a lot, sometimes up to four times a day. There were lots of obstacles like potholes, thunderstorms, running out of petrol, and going without food for 10 hours and a mere 200km after our departure point. But it was worth it.

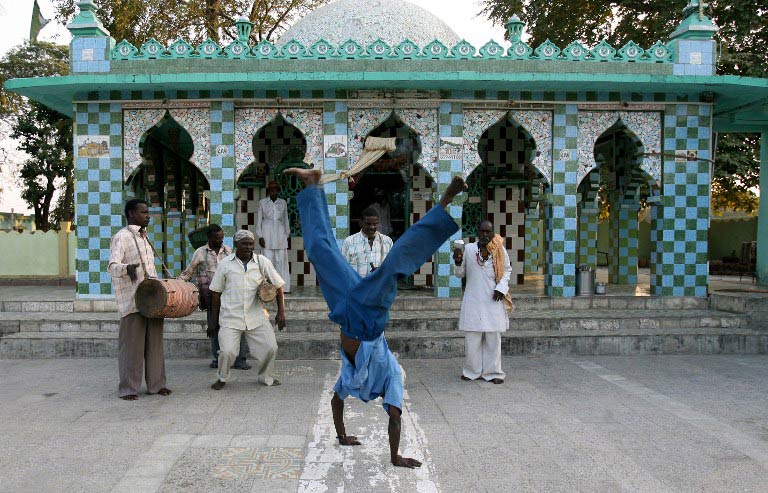

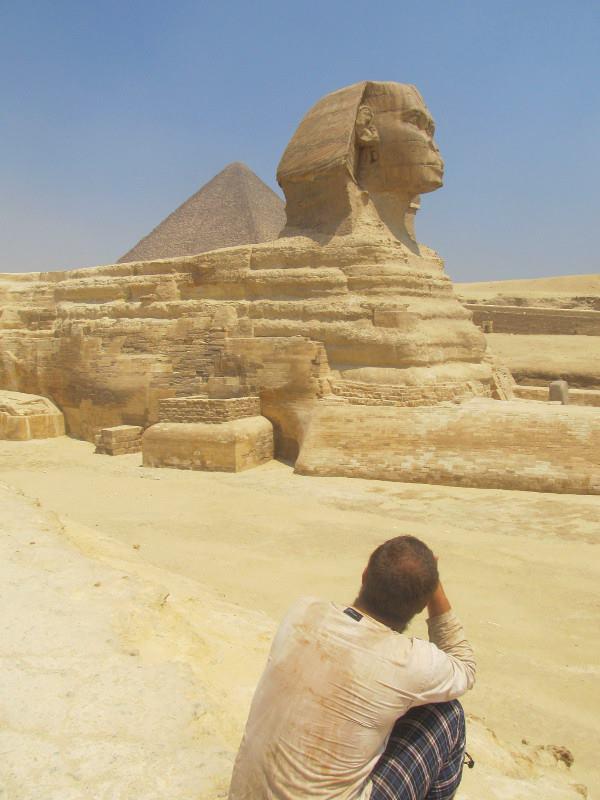

We just had look around us to fall in love with Africa all over again. Greeting shepherds walking with their cattle in Ethiopia’s highlands, almost hidden in the thick mist left by the passing rains. Stopping to watch a road race between competing schools on what is considered the main ‘highway’ between Rwanda and Tanzania, cheering with the crowd as the children finish their race, some barefoot, some wearing mismatched shoes, but all smiling the biggest smiles you’ve ever seen. Spending an hour with the magnificent mountain gorillas in Uganda. And if you drive for long enough, Africa rewards you with her unimaginable natural beauty too. Like when the clouds open for just long enough to reveal Mount Kilimanjaro watching over the landscape below her, or when the sun sets over the Meroe Pyramids in Sudan and all you hear is the silence of the desert echoing through the dunes.

We cried at the mass graves in Rwanda, and spent time in villages where the possessions of all the residents put together was worth just a little more than our bike. Yes, we were robbed once, lied to at times and were witnesses to some of the cruel realities of life in much of Africa. But most people we met were much more eager to share their stories of triumph and happiness while boasting about how beautiful their continent is, than focus on their suffering.

Cutting those strings and driving from South Africa to Cairo turned out to be so much more than what we bargained for, but the best thing we did was to rely on others to make it there. Every direction given by someone we met, whether right or wrong, was a friend made, a new adventure and a discovery of an African road less travelled. When we returned home in August 2012, we knew we’d had one of the biggest privileges in life – to discover Africa.

And our beloved but temperamental bike? At the end of our journey, we gave it to a friend we made on the border between Sudan and Egypt.

Dorette de Swardt lives in Port Elizabeth with her husband Guilllaume in a home that’s a recent upgrade from a two-man tent and self-inflatable mattresses that don’t inflate.