It is 14 years since the inaugural Caine Prize for African Writing was awarded to Sudanese writer Leila Aboulela at the Zimbabwe International Book Fair (ZIBF). And while the fortunes for the Prize – one of the most prominent for African writing – have grown, the same has not held entirely for Zimbabwe’s local literary scene.

Once a prestigious event attracting regional and international visitors, ZIBF now goes by largely unnoticed. Vibrant writers’ groups like Zimbabwe Women Writers (ZWW) and the Budding Writers Association of Zimbabwe (BWAZ) have faded into near oblivion, their prolific writers’ exploits no longer published. Kingston’s – one of Zimbabwe’s flagship bookstores – has closed down its main branch on Harare’s Second Street thoroughfare, the office space now occupied by an insurance firm.

This week, however, the Caine Prize returns for the first time to Zimbabwe with its annual workshop and public events to be held over two weeks between Harare and Mutare.

“Our return is partly based on the high number and quality of entries we receive from Zimbabwean writers, and the funding conditions that make such an expensive enterprise possible,” says Lizzy Attree, director of the Caine Prize for African Writing. “The Caine Prize has long wanted to hold a workshop in Zimbabwe and support Zimbabwean writers, but has not felt the environment was right until recently.”

Amid the economic and political decline that has exacerbated, and even prompted, the shrinking of the nation’s literary space, writing and publishing have continued. The Intwasa National Short Story competition still features as a prominent part of the Intwasa Arts Festival which takes place every year in Bulawayo; an award in the name of the late celebrated writer Yvonne Vera, who died in 2005 aged 40, is given as part of the competition. At the same time, Weaver Press and amaBooks – local publishing houses – continue to produce reputable titles of Zimbabwean fiction and non-fiction.

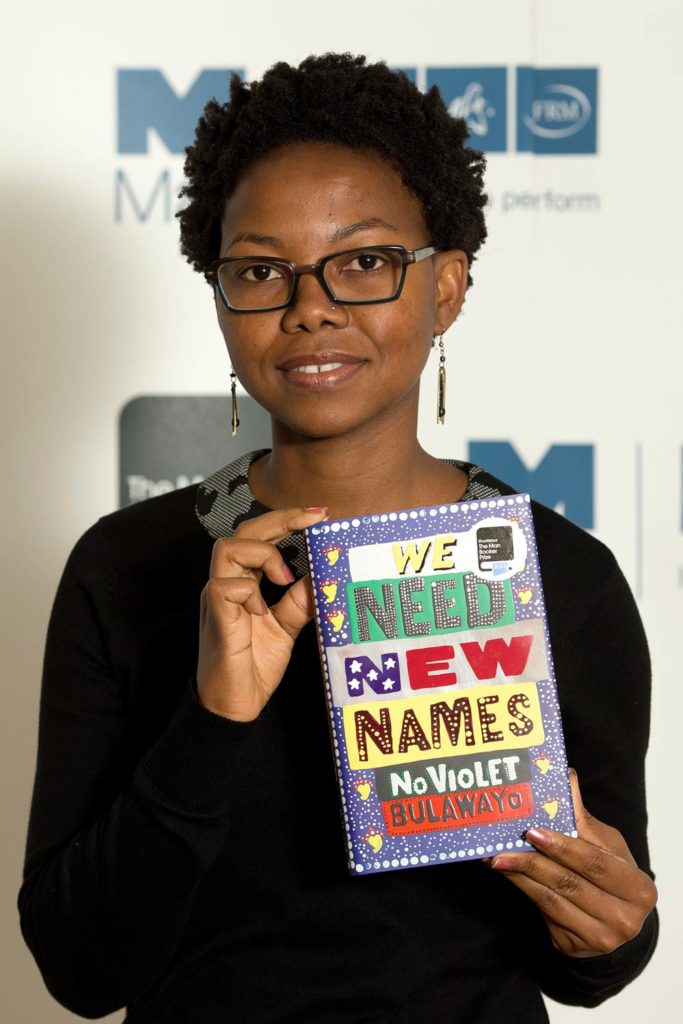

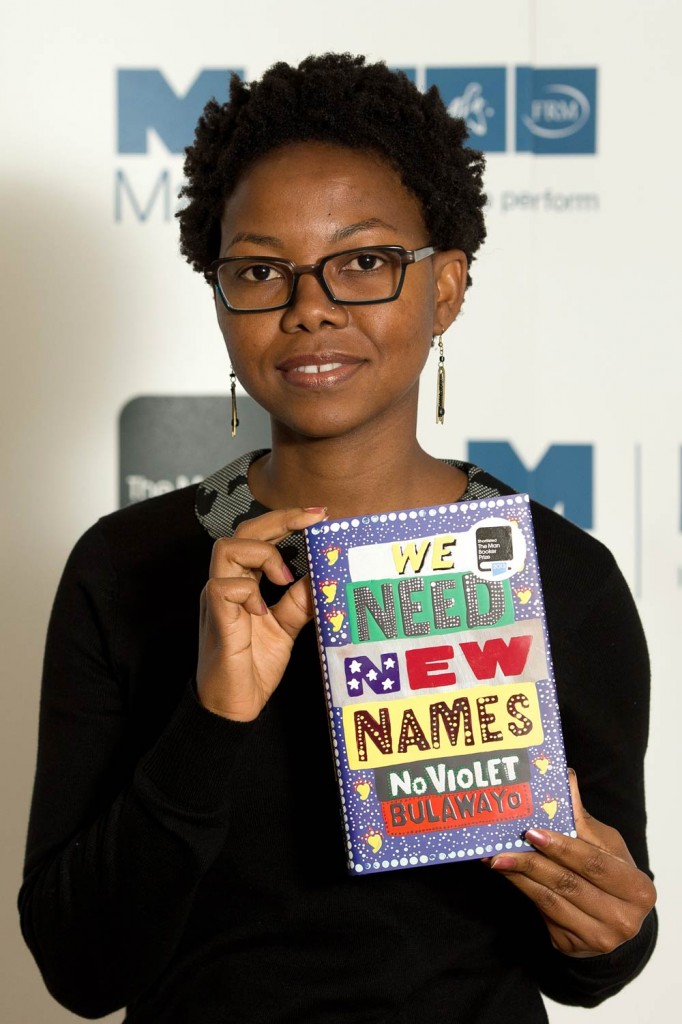

Two Zimbabwean writers, Brian Chikwava and NoViolet Bulawayo, have also won the Caine Prize with Bulawayo in particular going on to enjoy great success with her debut novel We Need New Names. Shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize last year and this year the winner of the inaugural Etisalat Prize for Literature, the novel’s first chapter is the 2012 Caine Prize winning short story, “Hitting Budapest”.

Beyond these successes, however, Zimbabwe’s literary space remains insular.

“Unfortunately reading, outside school or college syllabi, is not a priority for many people in Zimbabwe,” says Jane Morris, co-founder of amaBooks Publishers. “There are people in the country who do buy new books, but the number of such buyers is limited and discerning.”

Facing resource challenges and limited sales, Morris adds that the publishing house has had to become very selective in what it chooses to publish, at times turning down viable manuscripts. While a partnership with the Caine Prize to locally publish its annual anthology is helping to raise amaBooks’ profile, Morris again cautions that sales have been limited.

Young writers

Another issue that is immediately apparent is the dearth of young Zimbabwean writers being published.

“Of course, much can be done to augment literary spaces which already exist,” suggests Novuyo Rosa Tshuma who is one of the few currently published Zimbabwean writers under the age of 30. “However, I don’t believe young writers should wait to be spoon-fed.”

Tshuma, who is 26, bears testament to the fact that there is still a space for young Zimbabwean writers to claim, both locally and internationally. A previous winner of the Intwasa competition who has had her short fiction published in local anthologies by amaBooks, Tshuma has since gone on to release a novella and short story collection titled Shadows, which is published by South Africa’s Kwela Books. She is currently studying towards a Master of Fine Arts with the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the United States. At 22, she participated in the 2010 Caine Prize Writing Workshop held in Kenya.

“The question is, if an opportunity were to present itself today, would you have something written down on the page?” she asks.

Tshuma’s question is not easily answered, with a range of factors – some already highlighted – affecting young Zimbabweans’ endeavours, or lack thereof, into creative writing.

But it is one that fellow contemporary author, Tendai Huchu, would answer in the affirmative, having published his novel The Hairdresser of Harare with Weaver Press at the age of 28.

“What I believe though, with no empirical proof, is that, because Zimbabwe has a disproportionately sized diaspora, the nation’s literature reaps the benefits of having practitioners who interact with ideas from all across the world,” opines Huchu. “And that can only be enriching.”

Migration and transnationalism are prominent themes in Zimbabwean literature of the post-2000s; a trend underscored by the mass exodus of nationals during the political upheaval of the time.

Harare North, Chikwava’s novel offering, is set in London, for instance, while the protagonist in Bulawayo’s book, Darling, moves to Michigan to flee the political chaos of her Zimbabwean homeland. Guardian First Book Award winner, Petina Gappah, also wends in narratives of Zimbabwean life abroad into her 2009 short story collection, Elegy for Easterly.

But the Caine Prize is not without its critics, many of whom feel the initiative peddles an ideological agenda that provides a template of how to write about Africa, something ironically satirised by past Caine Prize Winner, Kenya’s Binyavanga Wainaina.

“Unfortunately, it makes bigger headlines to critique writing on the basis of subject matter, than on the basis of literary or linguistic style and accomplishment,” states Attree, adding that the hope of the Prize is to provide a window into a continent often misunderstood in the West. “If this window involves telling tales that are hard to read or which detail the often terrible events that occur in countries all over the world, then so be it.”

In dismissing the idea of an ‘authentic’ African or Zimbabwean narrative, and producing texts about such a space, Tshuma concurs.

“I encourage every writer to discard this word, ‘authentic’, from their vocabulary when writing,” she says. “There are many different Zimbabwes and different ways of seeing Zimbabwe; I don’t feel confined at all.”

Selected from seven African countries, the 13 workshop participants will each produce a publishable short story to be featured in the 2014 Caine Prize Anthology. The workshop runs from March 21 to April 2, with the writers also visiting with schools and engaging in public talks.

Fungai Machirori is a blogger, editor, poet and researcher. She runs Zimbabwe’s first web-based platform for women, Her Zimbabwe, and is an advocate for using social media for consciousness-building among Zimbabweans. Connect with her on Twitter.