Mention northern Nigeria and the first thing that may spring to mind is Boko Haram. Zainab Ashadu is hoping to change that — by selling designer handbags.

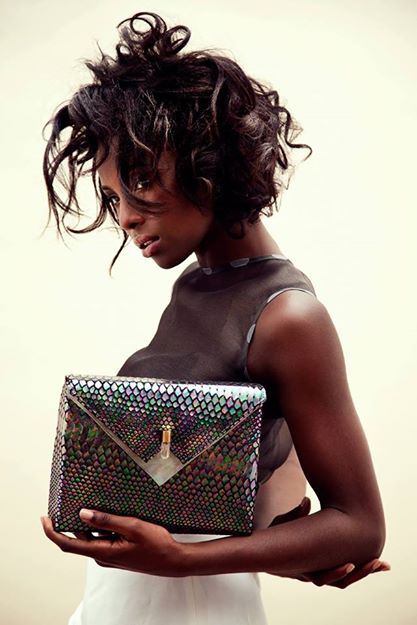

The Nigerian designer is the brains behind the Zashadu brand, whose modern, colourful creations use the ancient art of tanning and leather-dyeing from the country’s north.

“I think people like the story behind the bags. They like the fact that the bag has roots and origins,” the 32-year-old told AFP at her bustling workshop in a working class district of Lagos.

From the cramped premises in Festac, which buzzes with the sound of Singer sewing machines, a team of about half a dozen artisans make between 200 and 300 bags every year.

Ashadu’s parents were from the north, which is these days rarely out of the news because of the Islamist insurgency that has been raging since 2009.

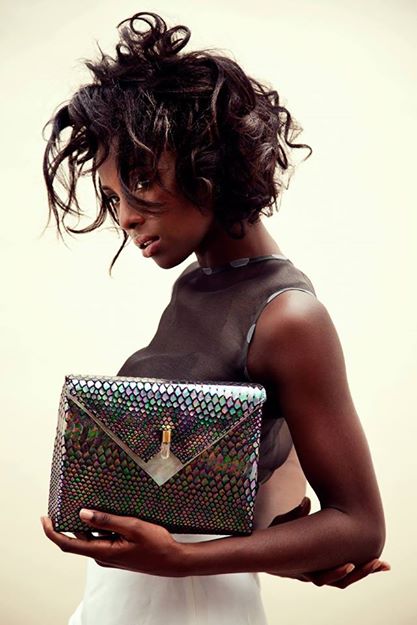

But the region has long been known for its high-quality leather, which the designer turns into clutch purses and handbags that sell overseas for between 150 – 800 euros.

The leather comes from the north’s biggest city, Kano, goatskin from the ancient northwestern city of Sokoto as well as python skin from snake farms in the region.

Sustainability, know-how

Unlike European fashion houses, which import raw leather from Nigeria and then tan and dye it overseas, Ashadu decided to make use of the centuries of know-how of artisans in Kano.

“It is very important for me to work in a sustainable way,” she said.

“I work with small families of tanners, the animals are traceable, we use vegetable dyes and other environmentally friendly dyes, and also the dyers work all together to save energy.”

The designer gets her inspiration from hours of hunting for bargains in the maze of stalls in the huge Mushin market, in the Lagos suburbs.

The market sells Nigerian leather off-cuts and rejects, particularly from Italian fashion houses.

“It’s so vibrant… there’s so much leather available and sometimes the sellers have no idea of the quality of what they sell,” said Ashadu.

“There’s antelope – that is very soft – there’s goatskin, sheepskin…”

From there, the material is turned into bags by her team, all of whom have been trained at a specialist school of leatherwork in the northern city of Zaria.

Adaptability

Ashadu is one of an increasing number of returning Nigerians or “repats”, chancing their arm in their home country after years spent overseas.

She spent her early childhood years in Lagos but was a teenager in London, where she was variously a model, actress, buyer and architecture student.

She came back in 2010 and has had to adapt to a different way of doing business.

“You need to be tough-skinned, adaptable and to have a great sense of humour,” she said.

“Nigeria is a very hard place to… do anything, let’s put it that way. It’s definitely very hard to run a business. But it’s more earthy. You feel like your feet are on the ground.”

Understanding and adapting to a different style of doing business is key to getting ahead, with some overseas firms looking to invest in Nigeria put off by red tape and logistical constraints.

Power cuts that often last more than 12 hours are a major problem and force businesses to invest in huge, costly electricity generators.

At Ashadu’s workshop, in a modest house belonging to her family, power comes from a small generator.

What’s important is adapting as much as possible to how her employees work, rather than trying to apply to the letter what she learnt at the London College of Fashion.

‘Made in Africa’

Zashadu bags have won a small but loyal following locally. Private sales have been held in unexpected locations such as a hotel suite with champagne and macaroons and at an upmarket yacht club.

In the last year, the brand, which is marketed online abroad, has established a presence in boutiques in London, Miami, Dublin, Johannesburg and most recently in Paris.

French designer Charlotte Ziegler, who sells Zashadu bags at the Franck et Fils department store, said she was intrigued by Ashadu’s unusual profile and also its “sustainable luxury”.

But she admits it was a risk.

“For 200 or 400 euros, people sometimes prefer to buy a product with a (recognised) designer label,” she said.

Ashadu is confident and knows that she’s tapped into a trend.

“People love Africa and Africa is something that is new in this way and people love to jump on bandwagons,” she said.

“And this one ticks all the boxes: it’s made in Africa, it’s beautiful-looking, it’s made sustainably, it’s international.”