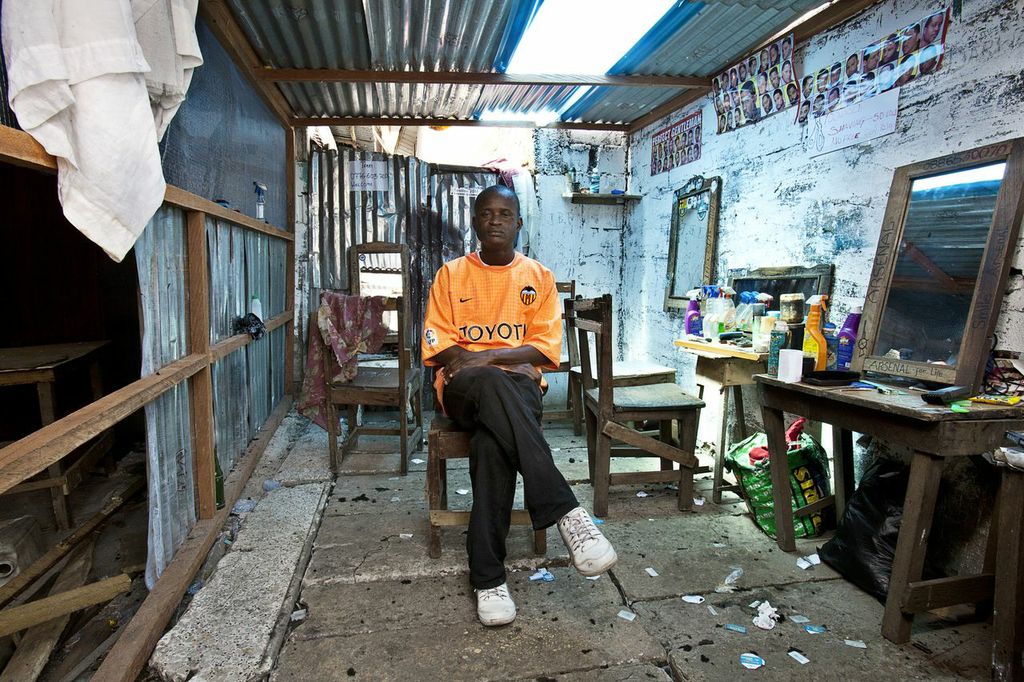

With all the skill of a master weaver at a loom, Esther Ogble stands under a parasol in the sprawling Wuse market in Nigeria’s capital and spins synthetic fibre into women’s hair.

Nearby, three customers – one in a hijab – wait for a turn to spend several hours and $40 to have their hair done, a hefty sum in a country where many live on less than $2 a day.

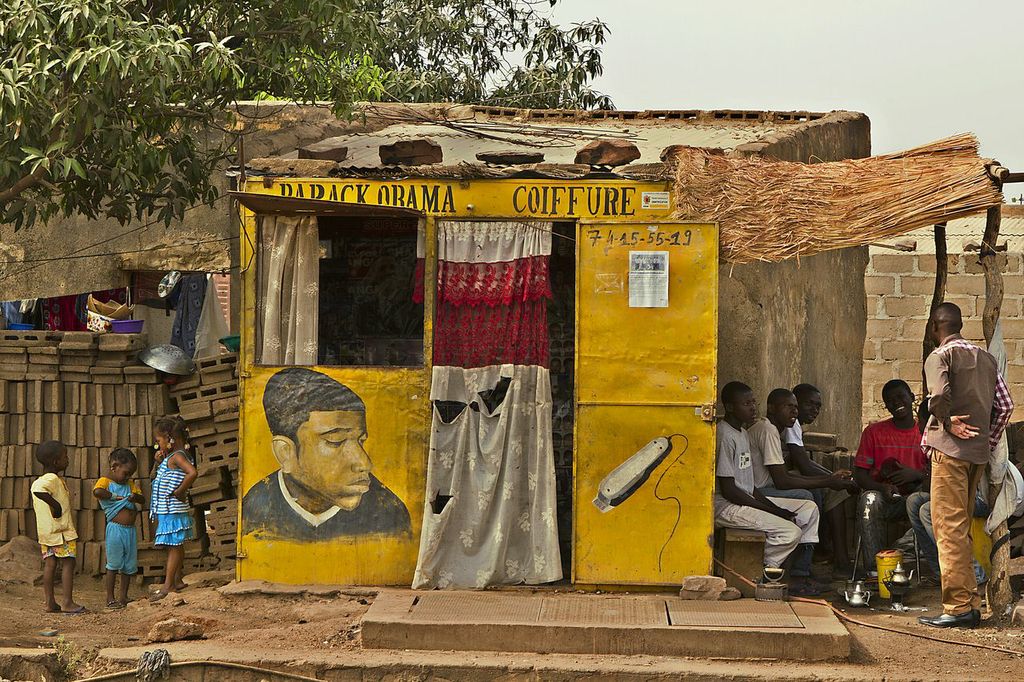

While still largely based in the informal economy, the African haircare business has become a multi-billion dollar industry that stretches to China and India and has drawn global giants such as L’Oreal and Unilever .

Hairdressers such as Ogble are a fixture of markets and taxi ranks across Africa, reflecting both the continent’s rising incomes and demand from hair-conscious women.

“I need to braid my hair so that I will look beautiful,” said 25-year-old Blessing James, wincing as Ogble combed and tugged at the back of her head before weaving in a plait that fell well past the shoulder.

While reliable Africa-wide figures are hard to come by, market research firm Euromonitor International estimates $1.1-billion of shampoos, relaxers and hair lotions were sold in South Africa, Nigeria and Cameroon alone last year.

It sees the liquid haircare market growing by about 5% from 2013 to 2018 in Nigeria and Cameroon, with a slight decline for the more mature South African market.

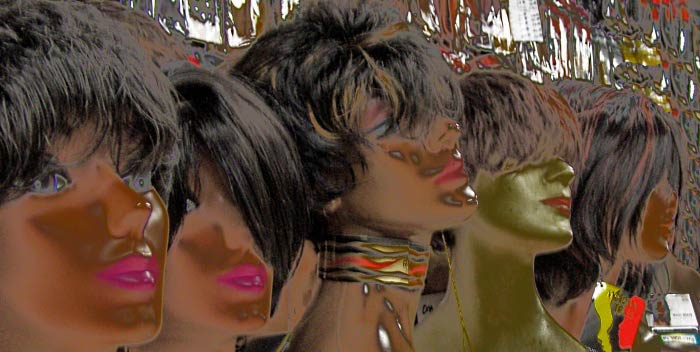

This does not include sales from more than 40 other sub-Saharan countries, or the huge “dry hair” market of weaves, extensions and wigs crafted from everything from synthetic fibre to human or yak hair.

Some estimates put Africa’s dry hair industry at as much as $6 billion a year; Nigerian singer Muma Geerecently boasted that she spends 500 000 naira ($3 100) on a single hair piece made of 11 sets of human hair.

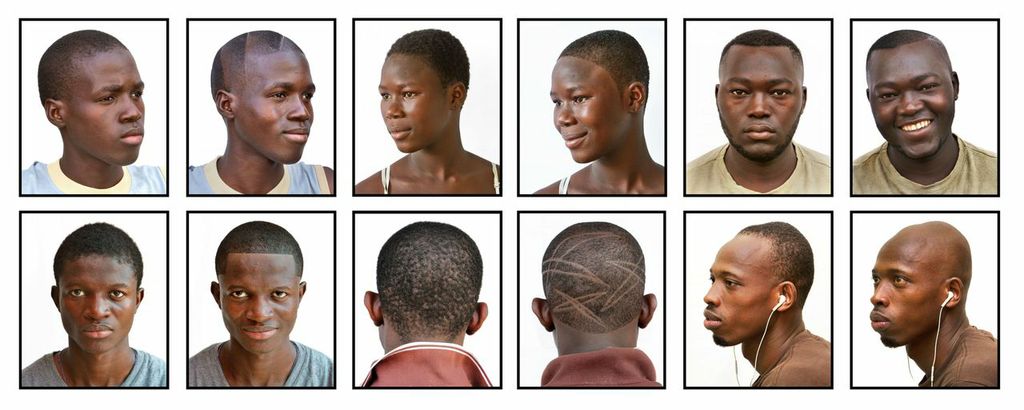

Informal economy

Haircare is a vital source of jobs for women, who make up a large slice of the informal economy on the poorest continent.

But business in Wuse market has slowed recently, said 37-year-old Josephine Agwa, because women were avoiding public places due to concerns about attacks by Islamic militant group Boko Haram.

The capital has been targeted three times since April, including a bomb blast on a crowded shopping district in June that killed more than 20 people.

“The ones that don’t want to come, they call us for home service,” she said as she put the finishing touches on a six-hour, $40 style called “pick and dropped with coils” – impossibly small braids that cascade into lustrous curls.

Nigerians are not alone in their pursuit of fancy locks.

“I get bored if I have one style for too long,” said Buli Dhlomo, a 20 year-old South African student who sports long red and blonde braids. Her next plan is to cut her hair short and dye it “copper gold”.

“It looks really cool. My mum had it and I also had it at the beginning of the year and it looked really good,” said Dhlomo, who can spend up to R4 000 rand ($370) on a weave.

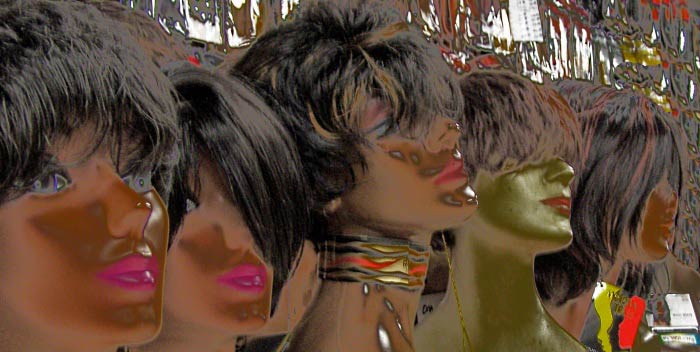

Daring styles

While South Africans change their hairstyle often, West Africans do so even more, said Bertrand de Laleu, managing director of L’Oreal South Africa.

“African women are probably the most daring when it comes to hair styles,” he said, noting that dry hair – almost unheard of a decade ago – was a growing trend across sub-Saharan Africa.

“Suddenly you can play with new tools that didn’t exist or were unaffordable.”

The French cosmetics giant this year opened what it billed as South Africa’s first multi-ethnic styling school, training students of all races on all kinds of hair, something that would have been unthinkable before the end of apartheid in 1994.

While the South African hair market remains divided, salons are looking to boost revenues by drawing in customers across ethnic groups, meaning hairdressers who once catered only for whites will need stylists who can also work on African hair.

L’Oreal is looking to build on its “Dark and Lovely” line of relaxers and other products with more research into African hair and skin and has factories in South Africa and Kenya producing almost half the products it distributes on the continent.

Hair from India, via China

Nor is it alone.

Anglo-Dutch group Unilever has a salon in downtown Johannesburg promoting its “Motions” line of black haircare products, and niche operators are springing up in the booming dry hair market.

“We supply anything to do with dry hair, across the board,” said Kabir Mohamed, managing director of South Africa’s Buhle Braids, rattling off a product line of braids, weaves and extensions that use tape, rings or keratin bonds.

Today there are more than 100 brands of hair in South Africa, making the market worth about $600-million, he said, roughly four times more than in 2005.

Much of the hair sold is the cheaper synthetic type and comes from Asia. Pricier natural hair is prized because it lasts longer, retains moisture and can be dyed.

India’s Godrej Consumer Products acquired South African firm Kinky in 2008 and sells synthetic and natural hair, including extensions, braids and wigs.

Buhle Braids, like its rivals, sources much of its natural hair from India, which has a culture of hair collection, particularly from Hindu temples or village “hair collectors”.

The hair is then sent to China where it is processed into extensions and shipped to Africa. Hair from yaks, to which some people are allergic, is now used less.

In one clue to the potential for Africa, market research firm Mintel put the size of the black haircare market in the United States at $684-million in 2013, estimating that it could be closer to $500 billion if weaves, extensions and sales from independent beauty stores or distributors are included.

What is certain is that Africa’s demand for hair products, particularly those made from human hair, is only growing.

“It hurts, but you have to endure if you want to look nice,” said Josephine Ezeh, who sat in Wuse market cradling a baby as a hairdresser tugged at her head. “Hair is very, very important.”