It’s another pretty day in Ngong with clear skies and chirping birds. Jackie, the newest member of my circle of parenthood help, has just returned home from fetching my son Shaka, who is three months away from turning five. As I open the gate, she says to me: “Mama Shaka, kitu kimefanyika!” Something has happened.

Tuesday is rubbish collection day in our town, which is located in the Great Rift Valley near Nairobi. My family has lived in Ngong for over 20 years, and no municipal or county rubbish removal initiatives have existed during this time. So local entrepreneurs came up with their own trash collection initiative, a service that we use at the moment. On this warm, summer’s day we put our trash out as usual for the truck to collect.

Jackie lives about 50 metres from my childhood home, and just 10 meters from the pile of trash at the end of our street. At 30 she is no shrinking violet, but she doesn’t say much. Today, however, she is more excited than usual. She tells me that a little baby boy has been found on top of the pile of rubbish. I don’t understand. Where is the child’s family, I ask? How do you tell a child to sit on a pile of rubbish? Jackie says she doesn’t know. No one knows. All they know is that the little baby was wrapped in a curtain and left there. A curtain. Now it makes sense. The little baby was aborted and dumped along with Tuesday’s trash.

While rummaging through the rubbish, a street child had found the aborted baby. It was a baby, not a foetus, because this abortion was carried out very late into the pregnancy. Jackie tells me that the child had all its parts – all it had to do was grow. She reckons it was five months or older. She laughs as she relates this to me, but her laughter is not out of malice or insensitivity. Like many others, she just didn’t know what else to say or do.

I ask Jackie why no one called the police. She says someone has to go to the police station and write a statement before they would come and collect the body. I want to do this – but with the law enforcement system here, there’s a chance that I would be questioned, and even suspected of the backstreet abortion. I’m a single mother, with no important surnames that can offer me any kind of protection, and no husband to come vouch for my moral worthiness. Saying the wrong thing at the wrong time to the wrong police officer would get me into trouble.

I go to cover the body. It is placed at the side of the road where children pass by on their way home from school. They do not need to see that. Worse still, they do not need to hear the conversations vilifying the woman or girl that had aborted the baby, and shaming the faceless and nameless doer of this ‘evil’. Someone ventures that they know whose curtain the baby is wrapped in – but fortunately a witch-hunt is not called for. In places like Ngong with slow justice systems and even slower delivery of public services like police protection, the people’s thirst for due process comes fast and furiously.

Abortions in Kenya

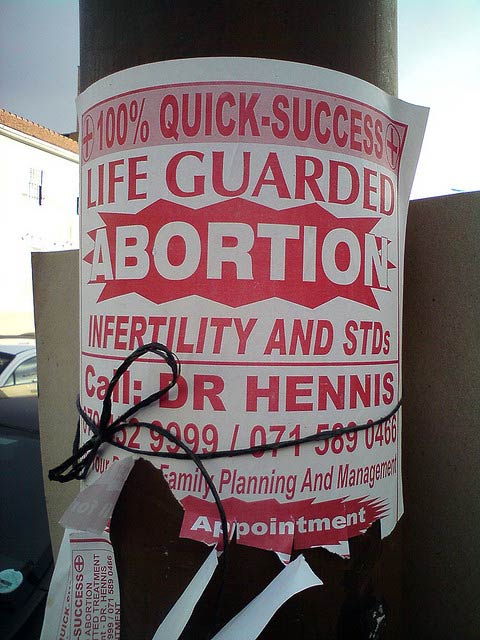

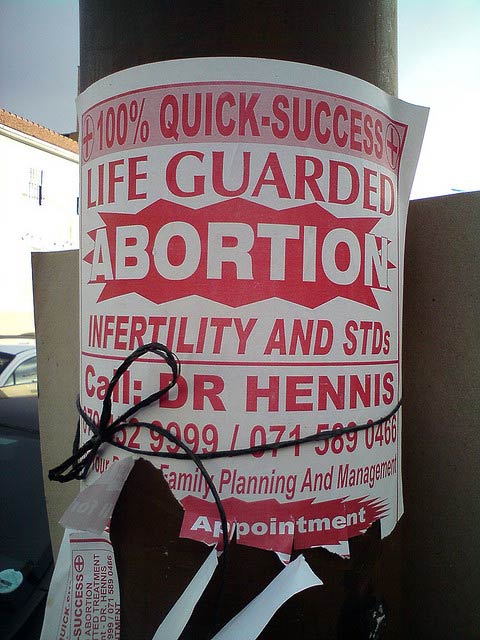

Kenya has one of the highest abortion rates in the world. Over 460 000 abortions were carried out in 2012 alone, according to research by the African Population and Health Research Centre (APHRC). The majority of these were due to unwanted pregnancies. Another survey revealed that more than 2 500 Kenyan women die annually from complications arising from unsafe abortions carried out by unqualified medical practitioners. Kenya relaxed its abortion laws in the new Constitution that passed in 2010. Before this, abortion was illegal unless except to save a woman’s life – and in this case, three doctors would have to approve a woman’s request for one. The new Constitution gives healthcare practitioners more latitude to determine when an abortion can be carried out. But as you can imagine, if the decision to grant a woman or girl an abortion lies in the hands of a healthcare professional, this leaves a lot to chance. Many Kenyans are still largely conservative when it comes to discourses on abortion, and chances that a nurse in a rural village will grant a 15-year-old with an unplanned pregnancy a requested abortion are very slim. Commenting on the APHRC report, researcher Dr Elizabeth Kimani said that there is still a lot of stigma in Kenya around access to abortion as a reproductive health right for women. The government is dragging its feet in upgrading not only the facilities to carry out abortions, but also initiatives to sensitise health care professionals on why there’s a critical need for conversations about abortion in the country.

Ten years ago, when I was in high school, I was subjected to a mandatory pregnancy test after what the school authorities found what they suspected was an aborted foetus in one of the dormitory bathrooms. The test was not a pee-on-a-stick type test. The school nurse carried out a vaginal exam, pressed down on my abdomen, and squeezed my nipples – to check for milk production, I guess. It was humiliating to say the least, and all the girls – nearly 1000 of us – had to undergo this. I could not imagine how or with what a fellow student could have carried out that suspected abortion. According to 2012 report by Kenya’s human rights commission, women take overdoses of anti-malaria medication or insert sharp objects like knitting needles and sticks into their bodies.

Back in Ngong, I dared to think about the woman that had just aborted this baby. She wasn’t a statistic in a report far away – she lived in my neighbourhood, she was close enough for me to have maybe met her or even spoken to her. Was she okay? Was she alone? Did she have help? Was she slowly bleeding to death in a little flat somewhere? Had she been raped? Was it an unplanned pregnancy? Maybe it was a case of incest, or maybe it wasn’t. To attempt a backstreet abortion this far into a pregnancy was an act of despair and desperation. The young woman or girl who did this really had no other choice. She didn’t. The people gathered by the side of the road did not ask these questions – all they saw was an aborted child, dumped on top of Tuesday’s trash.

I am unapologetically pro-choice. Restrictive laws and harsh social systems leave women and girls with such few options and virtually no bodily autonomy. And this goes beyond just the right to have safe abortions – it begins with a woman’s or a girl’s right to decide what happens to her body. A lot of underage sex is coerced and transactional. Many unplanned pregnancies are unwanted, even in marriage and in situations of perceived social stability. There’s no safety anywhere as far as women’s and girl’s bodies are concerned.

While society, religious organisations and indeed governments attempt to put their best moral foot forward, the reproductive and health rights of women and girls continue to suffer. And this suffering is not left to the women and girls alone – society suffers too. Women, men and children had to see an aborted child dumped on the side of the road, and the traumatic effects that witnessing such a sight can have on them goes ignored. As a passionate advocate for the right of women to choose, it was a humbling moment when I realised that these ‘issues’ are not happening ‘out there’ – they are happening right outside my front door, right on top of Tuesday’s trash.

*This post was edited to correct the number of abortions carried out in Kenya in 2012.

Sheena Gimase is a Kenyan-born and Africa-raised critical feminist writer, blogger, researcher and thought provocateur. She’s lived and loved in Kenya, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Zambia, South Africa, Botswana and Namibia. Sheena strongly believes in the power of the written word to transform people, cultures and communities. Read her blog and connect with her on Twitter.