“Africa is the final frontier in food,” says Malcolm Riley, a Zambia-born, Devon-based chef. He has a point. Trend-hungry Brits have latched onto everything from Korean to Peruvian cuisine in recent years, but Morocco (and perhaps Ethiopia) aside, we have yet to turn our culinary antennae towards Africa in a big way. Riley is on a mission to change all that, by spreading the word about African ingredients and cooking techniques. According to him, eating more sustainably-sourced baobab, shea butter and moringa could have health benefits for Britons and help create jobs in Africa. He hopes to achieve both with his line of African Chef products and so far, he is doing most of it from his kitchen in Newton Abbot, where he is now cooking me a traditional Zambian lunch and waxing lyrical about pumpkin leaves and Ray Mears.

Riley, whose father is English and mother is half-Indian, half-Zambian, moved to the UK when he was 25. Following stints working for Planet Organic and Riverford, he was itching to set up his own company: “I wanted to source an ethical product that rural communities in Africa could benefit from”. The first lightbulb moment came eight years ago when he was watching a Ray Mears documentary: “He was in the Sahara with the San tribe, using baobab seeds to make a coffee drink. I ate baobab as a kid but I’d never seen it used like that before.” Baobab trees grow all over Africa, and their fruit pulp is a rich source of Vitamins C and B2, iron, calcium and antioxidants.

Shortly after lightbulb moment #1, Riley took a trip back to Zambia and met Margaret Zimba of the Mthanjara Women’s Co-operative. Lightbulb moment #2: Zimba was making baobab jam and donating the surplus to children with HIV. She showed Riley how to make it and he decided to produce and sell baobab jam in the UK. He has since worked with Phytotrade Africa and the Eden Project (which has a tree in its Rainforest Biome) to source baobab sustainably and says that “harvesting the fruit can help double the income of 2.5m households in rural Africa”.

Riley is at pains to point out that promoting African ingredients and techniques is not the same as suggesting African food is one homogenous cuisine. “Across Africa the diversity of the food is phenomenal. We have influences from the Persians, the Portuguese, Dutch, English, French, and all the same spices that landed on the shores of India. There’s also great diversity among tribes. It could only be a village away where a dish totally changes.”

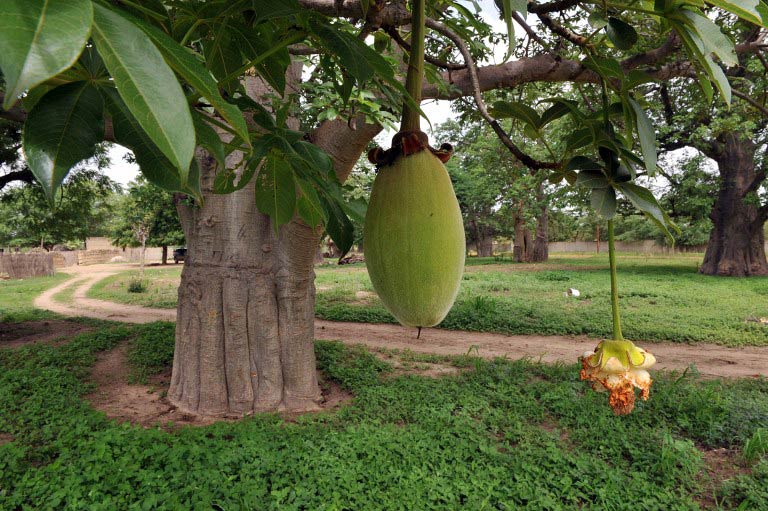

He shows me a baobab fruit – it looks like a hairless coconut. Inside are clusters of white, marshmallowy stuff: the pulp. This crumbles to a powder when you touch it. You can add the powder (which tastes a bit like mango, but tarter) to porridge, yoghurt, smoothies or condiments, like Riley’s fiery Baobab chill jam.

But baobabs are not the only ingredient he wants to shout about. There’s “smoky, fruity, complex” moringa, packed with B Vitamins and iron. The moringa tree is grown widely in hot countries and can be used in everything from curries to soft drinks. He also has some shea butter to show me – it’s not just for hand creams. This white, waxy substance from the nuts of the shea tree (found in many countries, including Ghana and Nigeria) “can be used for frying and roasting, or add a touch to a sauce before serving”. Riley is also hoping to visit Cameroon to learn more about the Safou – a type of plum.

Moreover, the health benefits of adding African influences to your cooking go beyond these exotic ingredients. According to Riley, the typical African diet is low-fat and high-fibre. Today he’s cooking us a typical Zambian meal of pap with village chicken (substituting thighs for the gamier bird you’d get in Zambia) and pumpkin leaves. Pap is a thick, white porridge made from maize meal (it’s also known as nshima in Zambia and sadza in Zimbabwe). “This is what fuels most of the continent. It’s high-fibre, gluten-free and extremely rich in a lot of vitamins.” It also stretches, as you need only one part maize to three parts water. “I can make a bag last two months,” says Riley who gets it from a South African shop (you can also find it on Amazon and eBay).

With shocking UK food-waste stats emerging almost daily, we can learn from such thriftiness – stretching ingredients, using cheaper cuts of meat (“My mum worked in a butchery, I grew up with brisket and shin”) and using neglected bits of veg. “Millions of pumpkins are grown for supermarkets – all of their leaves are left to rot.” Today Riley is cooking pumpkin leaves from his allotment with tomatoes and onions – a traditional combination in Zambia. They have a subtle, smoky flavour and you can use them instead of spinach.

What Riley has dedicated the last seven years of his life to, first with a brand called Yozuna, and now with the catchier African Chef, is bringing the best knowledge and ingredients from Africa to UK kitchens. If his ideas catch on, then both British cooks and African workers stand to benefit.

Katy Salter for the Guardian