Today relatives of more than 200 Nigerian schoolgirls kidnapped by Boko Haram are marking 500 days since the abductions, with hope dwindling for their rescue despite a renewed push to end the insurgency.

The landmark comes amid a worsening security crisis in the northeast, where Islamists have stepped up deadly attacks since the inauguration of President Muhammadu Buhari, killing more than 1 000 people in three months.

Boko Haram fighters stormed the Government Secondary School in the remote town of Chibok in Borno state on the evening of April 14 last year, seizing 276 girls who were preparing for end-of-year exams.

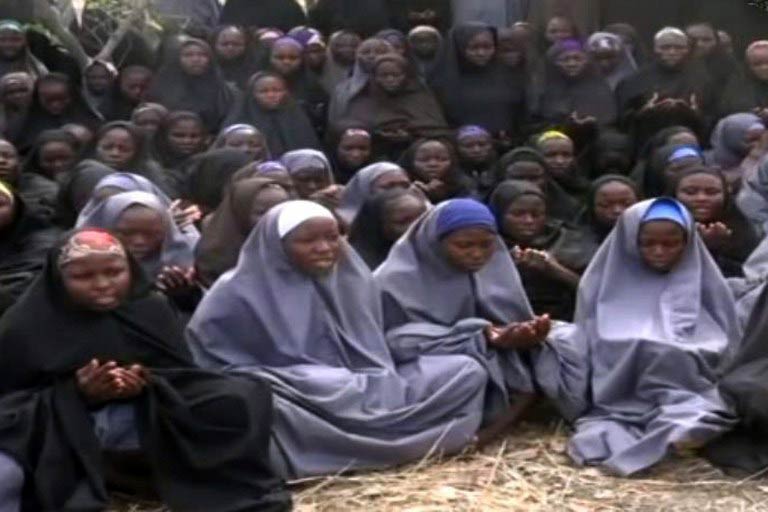

Fifty-seven escaped but nothing has been heard of the 219 others since May last year, when about 100 of them appeared in a Boko Haram video, dressed in Muslim attire and reciting the Koran.

Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau has since said they have all converted to Islam and been “married off”.

The Bring Back Our Girls social media and protest campaign has announced a youth march in the capital Abuja to mark the grim anniversary along with an evening candle-lit vigil.

Spokeswoman Aisha Yesufu said she was hopeful that the “right thing will be done?” under the new regime of Buhari, who replaced Goodluck Jonathan on May 29, vowing to crush Boko Haram.

“We have a new government. Yes, we have seen the kind of things he has done, his body language, what he has said about our girls. He has made them an issue,” she said.

Brutality

“He has given his word that he will do all he can to ensure the girls are rescued, not only to their parents, but for them to go back to school and continue with their lives.

“So we are hopeful that the right things (will) be done but at the same time we Nigerians should understand that the rescue of the Chibok girls is not a privilege … it’s their right as enshrined in the constitution of the federal republic of Nigeria.”

The mass abduction brought the brutality of the Islamist insurgency unprecedented worldwide attention and prompted a viral social media campaign demanding their release backed by personalities from US First Lady Michelle Obama to the actress Angelina Jolie.

Nigeria’s government was criticised for its initial response to the crisis and Western powers, including the US, have offered logistical and military support to Nigeria’s rescue effort, but there have been few signs of progress so far.

The military has said it knows where the girls are but has ruled out a rescue effort because of the dangers to the girls’ lives.

Boko Haram, blamed for killing more than 15 000 people and forcing some 1.5 million to flee their homes in a six-year insurgency, has rampaged across Borno since Buhari’s inauguration.

Global sex trade

The fresh wave of violence has dealt a setback to a four-country offensive launched in February that had chalked up a number of victories against the jihadists.

An 8 700-strong Multi-National Joint Task Force, drawing in Nigeria, Niger, Chad, Cameroon and Benin, is expected to go into action soon.

In a report published in April, Amnesty quoted a senior military officer as saying the girls were being held at different Boko Haram camps, including in Cameroon and possibly Chad.

The Chibok abduction was one of 38 it had documented since the beginning of last year, with women and girls who escaped saying they were subject to forced labour and marriage, as well as rape.

Fulan Nasrullah, a respected Nigerian security analyst and blogger who claims specialist knowledge of the inner workings of Boko Haram, said there was “no hope” of ever recovering most of the Chibok girls.

“Most have had kids by now and are married to their captors. Many have been sold into the global sex trade and are probably prostituting in Sudan, Dubai, Cairo and other far flung places,” he said.

“Some have been killed probably in attempts to escape, airstrikes on camps where they were being held, et cetera.” – By Ola Awoniyi