The Parisian audience is like a petulant child: very hard to please. So when French spectators and critics waxed eloquent over Cirkafrika, a show by an all-African circus troupe, I was intrigued, but pursed my lips à la française.

“Pfft!” I thought to myself, “What do they know? Yet another ho-hum repeat of contortionists and jugglers and human pyramids and dancers and unicyclists that are typical in plush resort hotels that line the Kenyan coast. Seen one, seen them all.”

A friend from Benin, also sceptical, went with his son to watch Cirkafrika and came away singing a new tune. “Mesmerising,” was his text message. That gave me food for thought.

So tickets were bought for an adult and three children for the show, which runs for over two hours. The children were to be the jury, with the main judge being my three-year-old whose attention span is pretty good – 30-40 minutes tops.

The French circus, Cirque Phénix, produced Cirkafrika. Cirque Phénix’s aim is to present novel artistic creations each new season. Having no proper circus tradition to speak of in Africa – we have only four big tops: one based in Egypt, two in South Africa and one in Tanzania – unlike the Chinese and Eastern Europe circus heavyweights, it is not surprising that Paris sat up and paid attention to Africa coming to town.

While looking for African talent comparable to circus chefs-d’oeuvre from Moscow and Peking, Alain M. Pacherie, the founder and director of Cirque Phénix, turned to the Zip Zap Circus (South Africa) and Circus Mama Africa (Tanzania). What was once a germ of an idea – an African show, unlike any other, in Paris – became a reality a few years later.

This was the reality we went to discover on a recent wintry Saturday afternoon in Paris.

The artists from South Africa, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Ghana, the Congo and Guinea; the costumes; the stage decor; the giant 3D animal and bird marionettes; the music – Lion King, move over! – were all made in Africa.

Forget clichéd African folklore and dancers garbed in traditional attire welcoming an African president or some other dignitary; forget the cold disciplined professionalism of Chinese acrobats and the aloof masterful excellence of trapeze artists from eastern Europe; forget the crisp, pasted smiles of chorus-line girls dancing the French cancan.

How could one not stand up, from the word go, and dance to Miriam Makeba, Youssou N’Dour or Touré Kunda numbers sang by three African musicians accompanied by a Big Live all-African band?

I felt Pata Pata.

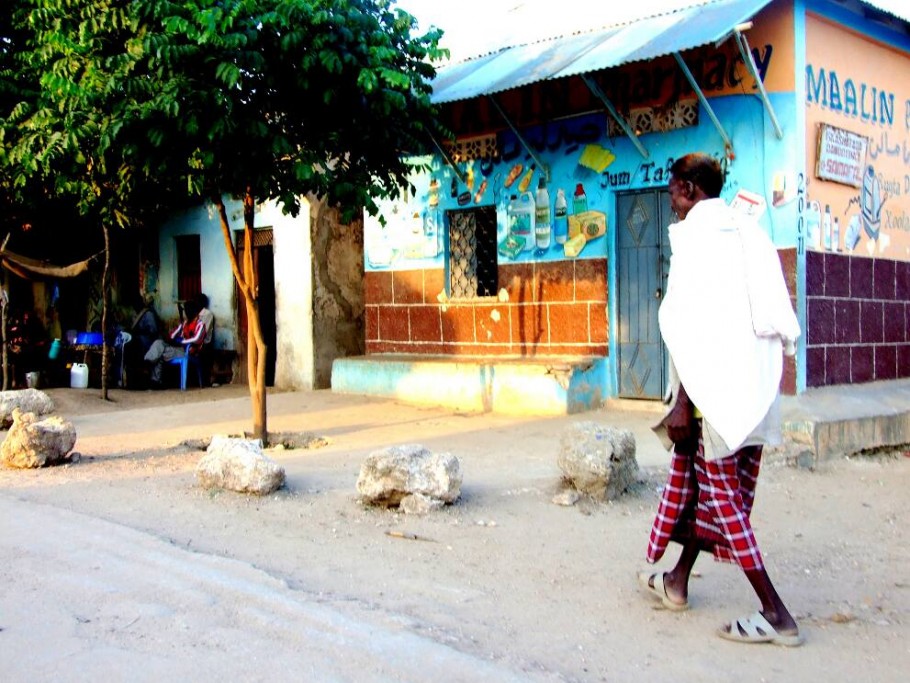

The splash of colours from the costumes, decor and music reminded me of an African marketplace with its pyramid arrangement of colourful fruits and vegetables, and people talking, gossiping, haggling and laughing with music blaring from a nearby stall.

Cirkafrika is oh so cheerful, the music vibrant and the artists generous. The children couldn’t get bored even if they’d wanted to.

The artists – all very professional, focused and elegant in their performances – made their acts look so easy. They were genuinely having fun, their joy so contagious that I longed to join them on stage even though I have no circus skills.

Large, colourful plastic wash basins that can be found in African households replaced plates and bowls in the plate-spinning contortionist’s act. The artist spun five of them at a dizzying speed – one per limb and the fifth was spun using his mouth. The act was accompanied by vibrant dancing.

The colourful basins took me back to Saturday mornings in Kenya: tending to household chores after breakfast using similar kinds of basins, the same ones that hold grain and spices sold at the market. Cirkafrika was a ray of warm tropical sunshine in the middle of a European winter.

The Ethiopian hoop artist made me forget that she was manipulating hula hoops. What I saw was a Samburu woman beautifully adorned with handmade beaded ornaments.

Cirque Phénix never presents animal acts as a matter of principle, but what would Africa be without her rich fauna and award-worthy costumed artists on stilts? The children saw an animal parade of graceful giraffes, tropical birds, crocodiles and a life-size elephant. And the frog! Oh the lithe green human frog, padded feet, croaking and all. How on earth did he manage to fit into that little transparent box?

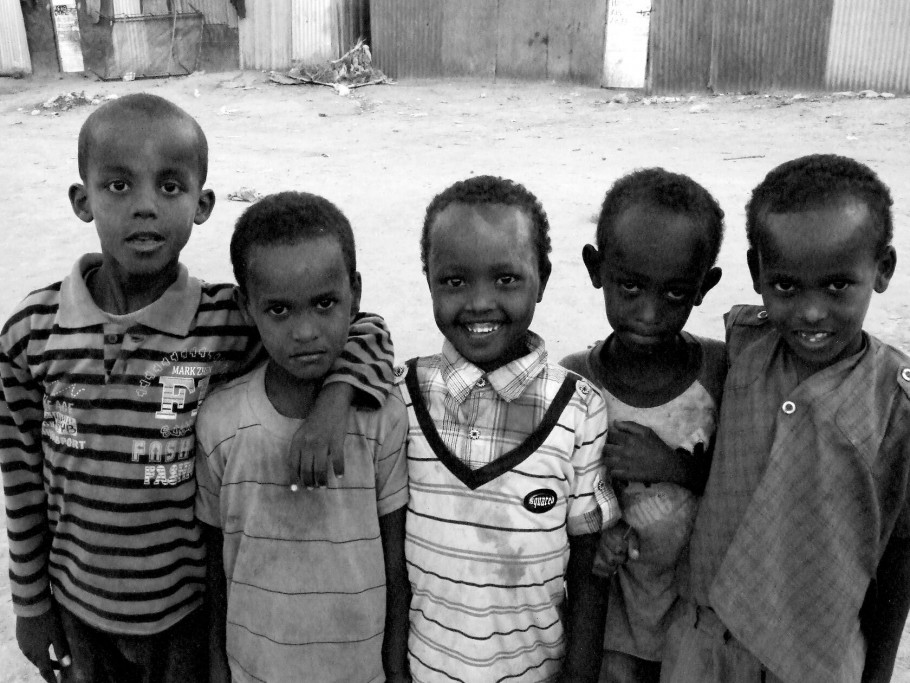

South Africa’s gumboot dancers made us long for more. So we asked for one encore and a second encore and yet another encore. We danced and we celebrated Africa. We saw the other face of the continent that has potential and talent and that can adapt and excel while preserving its Africanness.

Cirkafrika whispered that we can dare to dream and to believe in Africa because Africa’s got talent!

My children’s verdict? If Cirkafrika comes to a big top near you, drop whatever you are doing and run, don’t walk, to see it.

I agree.

The show, now on the road in Switzerland, Belgium and Ukraine, will be back in France/Europe in Winter 2013.

Jean Thévenet, a work-at-home mum, was born and raised in Kenya. She now lives in France and blogs at http://hearthmother.blogspot.com.