Egyptian graffiti artists are doing more than just painting art on street walls. They’re creating social awareness campaigns against corruption, media brainwashing, poverty and sexual harassment, and also using graffiti to beautify slum areas of Cairo to restore a sense of pride, ownership and hope to residents.

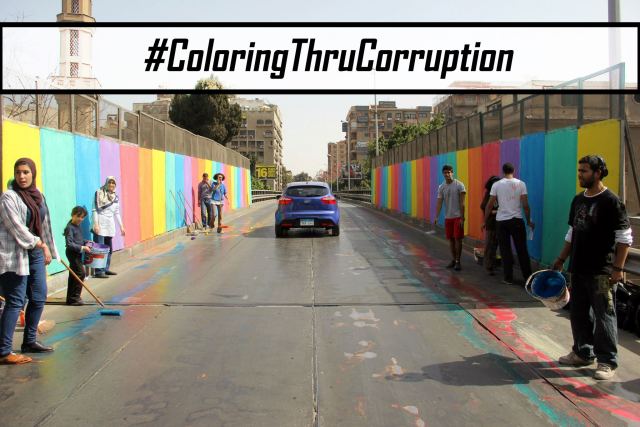

Nazeer and Zeft have launched a new awareness campaign called #ColoringThruCorruption, where they paint walls, water pipes and other public surfaces to raise awareness about corruption and how the Egyptian government is stealing money from its citizens. As Nazeer explains:

We’re not painting to make life pretty – on the contrary, this is our way of drawing your attention to the reality of the situation: the government is stealing your money, the taxes you pay every year to renew your car license, pay your traffic tickets, pay for the roads, bridges and highways to be maintained, pay for your water/gas/electricity bills and so on. This money goes into the personal accounts of the governors and the local councils. In the end, you find the roads ruined and full of holes that damage your cars. So many homes without access to water or electricity or gas. This is the devastating reality. We’re painting corruption to draw people’s attention and then tell them our message. This time we were ten people painting. Next time we’ll be twenty, forty, sixty, a hundred with God’s will. We will paint the slum areas. The biggest proof of corruption is when one man lives in a palace and across the road, another man lives in a slum.

Zeft’s previous campaigns include his Nefertiti mask graffiti, which was endorsed by anti-sexual harassment campaigns and spread to protests around the world in support of Egyptian women.

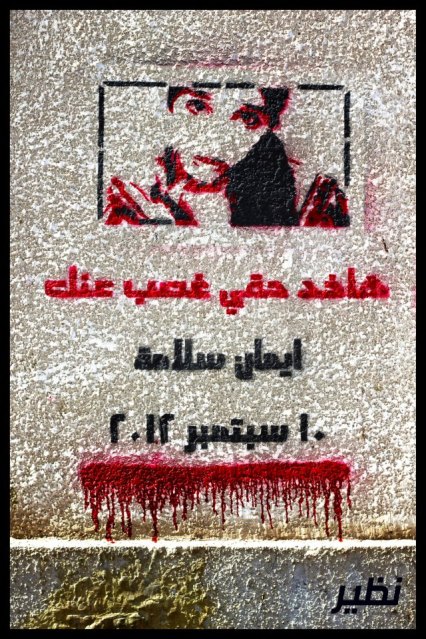

Nazeer’s previous campaigns include graffiti calling for a return to protests in Tahrir during 2011, and his graffiti of 16-year-old Iman Salama, who was shot dead in September 2012. Nazeer made the stencil for the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, an NGO that wanted to draw attention to Iman’s murder, which had received little media coverage.

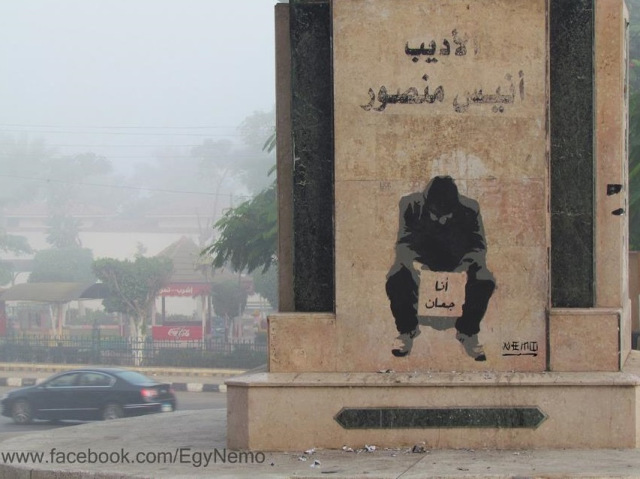

Nemo is a street artist in Mansoura who has made graffiti that raises awareness about street children, homeless people, poverty and sexual harassment. He is one of the most diligent street artists in Egypt and has dedicated pretty much every single graffito he’s made to honouring martyrs, advocating the revolution and drawing attention to the impoverished and disenfranchised millions of Egyptians. He is featured in the upcoming documentary In the Midst of Crowds, and all his images can be viewed on his Facebook page.

In his latest campaign, he plasters sliced photographs of Egyptian faces on the iron walls of Gamaa Bridge in Mansoura. This one below is my favourite. It’s of Abo El Thowar, who has become an icon of the Tahrir protests for his resilience and poetic protest posters.

Then there’s the Mona Lisa Brigades, who created the great ‘I want to be’ project. The artists painted on the walls of people’s homes in the Cairo slum of Ard al-Lewa. The children of the neighbourhood were photographed and their images made into graffiti on the walls of the narrow, grim alleyways.

Such a simple gesture can bring so much hope and joy to an otherwise neglected neighbourhood. Using graffiti to beautify an area has an effect on the entire neighbourhood because it restores a sense of pride and ownership. The project is a great example of using street art to help a community.

“After doing a great deal of research in Ard al-Lewa, we discovered there were thousands of children who have had almost no voice or representation throughout this movement, Mohamed Ismail, one of the founding members, told Egypt Independent. “We sprayed stencils of their faces along the walls. Under each image, we included the child’s dream. This way, whenever those kids walk by their faces on the wall, they will never forget their dreams.”

All of these initiatives are good examples of putting street art to good use, diverting it from its usual political course to spread positive messages, educate, raise awareness and help others that are completely ignored by the state. These artists are great people and deserve credit and recognition for their hard work. I hope they get it.

Soraya Morayef is a journalist and writer in Cairo. She blogs at suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com, where this post was first published. All pics above have been sourced by her. Connect with her on Twitter.