I wake up on election day in April 1980. Black Zimbabweans are learning to vote for the first time. It’s early in the morning. With no experience of voting, I reflect on the risk of spoiling the ballot paper. I feel like a child going to school for the first time. No one I know can give me an idea of what a ballot paper will look like.

Triangle Sugar Estate in south-eastern Zimbabwe can be a lonely place. It is just you and a few familiar faces, fellow teachers and cane cutters who are usually covered in black soot from the burning sugar cane.

When they cut cane, they don’t talk. Layers of black ash cover their faces. Perhaps they feel humiliated by their appearance. It is better to meet them in their clean states, not in sugar cane cutting gear. You just wave at them and leave them to meet their daily tonnage of harvested sugar cane. The stacks of cane they cut decide their earnings. There is no monthly salary. It is hard labour.

My friends and I have asked the company for permission to campaign for the Patriotic Front. It is granted, but on one condition: if the party of “terrorists” loses, we will all lose our jobs. We take the risk, print party T-shirts with party slogans for sale, and raise enough money for our fragile campaign.

In our small cars, we go from section to section, campaigning, making house visits and small speeches. No rallies. We walk and whisper the new political wind of change into all ears.

Then the day of the rally comes, and the big men arrive: Dzingai Mutumbuka, Dzikamai Mavhaire, Nolan Makombe, Basopo-Moyo, Nelson Mawema and other previously banned politicians.

A new destiny

There are speeches, and more speeches, and promises. Then there is spontaneous dancing and singing, men and women in a frenzy at the possibility of freedom, a new destiny.

With our poverty haunting us, hiring buses is a luxury out of our reach. People walk long distances to Gibo Stadium. That is the first rally of the “terrorists”, as the sugar company calls them. Thousands pack the stadium, singing and dancing. It is a joyous occasion.

It is the arrival of our dignity, freedom, a new self, a new nation, a fresh map of our destiny written in our own ink, even if that ink might be our blood.

Soon after that, on a Tuesday morning, I am at the garage to get my car fixed. The young white lady serving me has a small radio on her desk. She is slow to serve me. It is news time.

She fiddles frantically with the radio knob to get the best reception to listen to the election results before attending to me. She tells me that “Bishop” Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa is going to win. “Such a holy and gentle man,” she says.

But, in a few minutes, the British election official belts out the results.

The woman breaks down, crying. I try to help her up, to console her, as she shouts: “Terrorists! Terrorists! The British have let us down! Terrorists! I am leaving! Terrorists!” As I try to calm her down, her boss enters and takes her away. He thinks I have offended her. I tell him it was the election results. He nods and makes out my receipt. I pay and get my car keys.

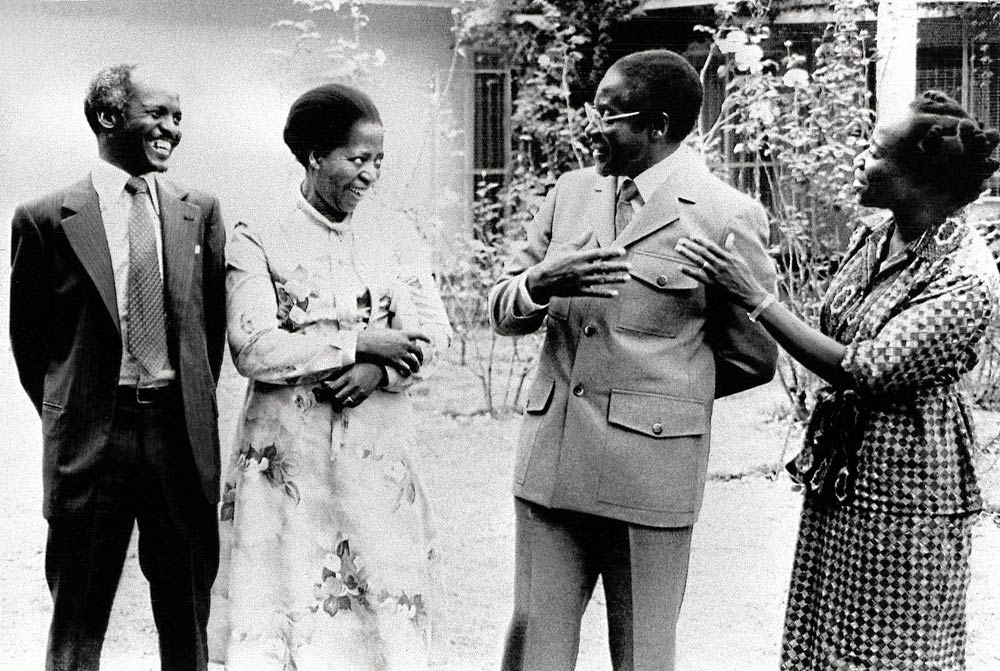

A few days later, on April 18, the party does not seem to have come to an end. Far off, in Harare, Bob Marley graces the independence celebrations overseen by Robert Mugabe and Prince Charles. It’s an event of two Bobs and the Wailers.

My friends and I are no longer enemies of the sugar company. We are the new heroes. The threats of dismissal are rescinded.

We are invited to all the formerly prohibited venues for celebration. The sugar company buys all the chickens available from local butcheries. Cows and bulls are donated to the festivities. And the party goes on for what seems like eternity.

The dancing! Oh, the dancing! The eating. The music! The orderly chaos! One man, a Mr Chikanga, challenges anyone to a chicken-eating contest. He devours five large roasted birds in a few minutes.

Another man, primary school teacher Mr Chidhumo, the father of infamous convicted murderer and robber Stephen Chidhumo, dances until he breaks his leg. He ignores the pain until we call an ambulance and he is forced to abandon the party for the hospital.

He insists on taking his whisky glass with him to the hospital, but the ambulance driver will have none of it. The driver grabs the glass and drinks it himself. It is celebration time, and no one wants to be left out. All is forgiven.

April 18, the day a new national flower was born, still lingers in my imagination.

It was a day of hope and pride, the arrival of a new self, a new being, a fresh flower of our human dignity. Prime Minister Robert Mugabe’s “swords-to-ploughshares” speech enkindles our hope further.

Like the Bulawayo statue, we “look to the future” with an incisive sense of aspiration in our hearts.

The birds of hope have deposited new eggs in our hearts of hope, a new destiny is possible, we say to our silent but smiling hearts.

I wake up on election day in April 1980. Black Zimbabweans are learning to vote for the first time. It’s early in the morning. With no experience of voting, I reflect on the risk of spoiling the ballot paper. I feel like a child going to school for the first time. No one I know can give me an idea of what a ballot paper will look like.

Triangle Sugar Estate in south-eastern Zimbabwe can be a lonely place. It is just you and a few familiar faces, fellow teachers and cane cutters who are usually covered in black soot from the burning sugar cane.

When they cut cane, they don’t talk. Layers of black ash cover their faces. Perhaps they feel humiliated by their appearance. It is better to meet them in their clean states, not in sugar cane cutting gear. You just wave at them and leave them to meet their daily tonnage of harvested sugar cane. The stacks of cane they cut decide their earnings. There is no monthly salary. It is hard labour.

My friends and I have asked the company for permission to campaign for the Patriotic Front. It is granted, but on one condition: if the party of “terrorists” loses, we will all lose our jobs. We take the risk, print party T-shirts with party slogans for sale, and raise enough money for our fragile campaign.

In our small cars, we go from section to section, campaigning, making house visits and small speeches. No rallies. We walk and whisper the new political wind of change into all ears.

Then the day of the rally comes, and the big men arrive: Dzingai Mutumbuka, Dzikamai Mavhaire, Nolan Makombe, Basopo-Moyo, Nelson Mawema and other previously banned politicians.

A new destiny

There are speeches, and more speeches, and promises. Then there is spontaneous dancing and singing, men and women in a frenzy at the possibility of freedom, a new destiny.

With our poverty haunting us, hiring buses is a luxury out of our reach. People walk long distances to Gibo Stadium. That is the first rally of the “terrorists”, as the sugar company calls them. Thousands pack the stadium, singing and dancing. It is a joyous occasion.

It is the arrival of our dignity, freedom, a new self, a new nation, a fresh map of our destiny written in our own ink, even if that ink might be our blood.

Soon after that, on a Tuesday morning, I am at the garage to get my car fixed. The young white lady serving me has a small radio on her desk. She is slow to serve me. It is news time.

She fiddles frantically with the radio knob to get the best reception to listen to the election results before attending to me. She tells me that “Bishop” Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa is going to win. “Such a holy and gentle man,” she says.

But, in a few minutes, the British election official belts out the results.

The woman breaks down, crying. I try to help her up, to console her, as she shouts: “Terrorists! Terrorists! The British have let us down! Terrorists! I am leaving! Terrorists!” As I try to calm her down, her boss enters and takes her away. He thinks I have offended her. I tell him it was the election results. He nods and makes out my receipt. I pay and get my car keys.

A few days later, on April 18, the party does not seem to have come to an end. Far off, in Harare, Bob Marley graces the independence celebrations overseen by Robert Mugabe and Prince Charles. It’s an event of two Bobs and the Wailers.

My friends and I are no longer enemies of the sugar company. We are the new heroes. The threats of dismissal are rescinded.

We are invited to all the formerly prohibited venues for celebration. The sugar company buys all the chickens available from local butcheries. Cows and bulls are donated to the festivities. And the party goes on for what seems like eternity.

The dancing! Oh, the dancing! The eating. The music! The orderly chaos! One man, a Mr Chikanga, challenges anyone to a chicken-eating contest. He devours five large roasted birds in a few minutes.

Another man, primary school teacher Mr Chidhumo, the father of infamous convicted murderer and robber Stephen Chidhumo, dances until he breaks his leg. He ignores the pain until we call an ambulance and he is forced to abandon the party for the hospital.

He insists on taking his whisky glass with him to the hospital, but the ambulance driver will have none of it. The driver grabs the glass and drinks it himself. It is celebration time, and no one wants to be left out. All is forgiven.

April 18, the day a new national flower was born, still lingers in my imagination.

It was a day of hope and pride, the arrival of a new self, a new being, a fresh flower of our human dignity. Prime Minister Robert Mugabe’s “swords-to-ploughshares” speech enkindles our hope further.

Like the Bulawayo statue, we “look to the future” with an incisive sense of aspiration in our hearts.

The birds of hope have deposited new eggs in our hearts of hope, a new destiny is possible, we say to our silent but smiling hearts.

Chenjerai Hove is a Zimbabwean writer living in exile in Europe. This piece was first published in the Mail & Guardian’s Zimbabwe edition.