A man wobbled across the podium leaning heavily on his crutches as the preacher beckoned to him with outstretched hands. The mammoth crowd at the Kamukunji grounds in Nairobi fell silent in anticipation. The preacher asked the man a few questions and then boomed into the mic: “In the name of Jesus I command you to walk!” The man immediately threw down his crutches and trod unsteadily around the stage. The crowd burst into delirium. Some people fainted.

My colleague who was standing besides me shook with quiet laughter. He knew the “disabled” guy, Joel, since they both live in the Kangemi neighbourhood. Joel is a hopeless drunkard. To finance his drinking habit, he takes on casual jobs – like this one.

Kenyan worshippers are seeking divinity in “miracle” churches and dubious pastors who’ve sprung up all around the country. They command a huge following and are raking in money – millions, even – through, among other things, their claims of miracle healing. One session can cost as much as R300. In addition to this and weekly donations from congregants, the pastors sell anointing oils which cost between R15 to R50 a bottle. The oils have a short shelf life – anything from a few days to a month – so believers have to stock up on them regularly to keep “miracles” flowing in their lives. No wonder, then, that these religious leaders can afford posh mansions and Range Rovers – and that they make the news for the wrong reasons.

Take Pastor Michael Njoroge of Fire Ministries, who reportedly slept with a prostitute last year and then hired her for R200 to attend his Sunday mass service with a disfigured mouth. With a cloth covering her mouth, sobbing because of her shame, the woman performed like a pro in front of cameras. Njoroge, who has a slot on a Christian TV station, prayed for her at his service. The next day she was back in his church with a perfect mouth, giving testimony of the miracle in front of a transfixed crowd. Soon after the incident Njoroge was exposed by Kenyan news channel NTV but his loyal congregants stood by him.

Then there’s the billionaire businessman, politician and pastor Kamlesh Pattni, who was charged with conspiracy to defraud the government of Sh58-billion in the Goldenberg scandal. He was cleared of the charges in April 2013 but not of his notoriety. Pattni has established his own church and provides a free lunch to his growing congregation every Sunday. Who doesn’t want a free meal?

Pattni could soon be receiving a hefty Kh4-billion of taxpayers’ money after winning a legal tussle over exclusive rights to duty-free shops in two Kenyan airports. The hefty award, however, is being challenged.

Let’s not forget Pastor Maina Njenga, the former leader of Mungiki, a criminal gang known for extortion, ethnic violence, female genital mutilation and other horrific crimes including the beheading and skinning in its strongholds in Nairobi and central Kenya. He spent a long stint in jail and was released from prison in 2009. Njenga then became a born-again Christian, and set up Hope International Ministries. He professed that he changed his life around but few believe him.

Like many Kenyan pastors, he was quick to enter business and politics too. Last year he threw his hat into the ring for the presidential race but quit due to a lack of funds.

Money troubles are not something Bishop Allan Kiuna and his wife Reverend Kathy have to worry about. The influential, doting couple run the Jubilee Christian Centre in Nairobi which has an ‘international media ministry’ with video and music production and book publishing. They’ve come under fire for their luxurious lifestyle on social media, but Reverend Kathy makes no apologies. “We serve a prosperity God,” Kathy said in an interview with True Love magazine. “God wants us to be prosperous in every single way. His desire for us is to walk in abundance. I am praying for church people to show the likes of Bill Gates dust!”

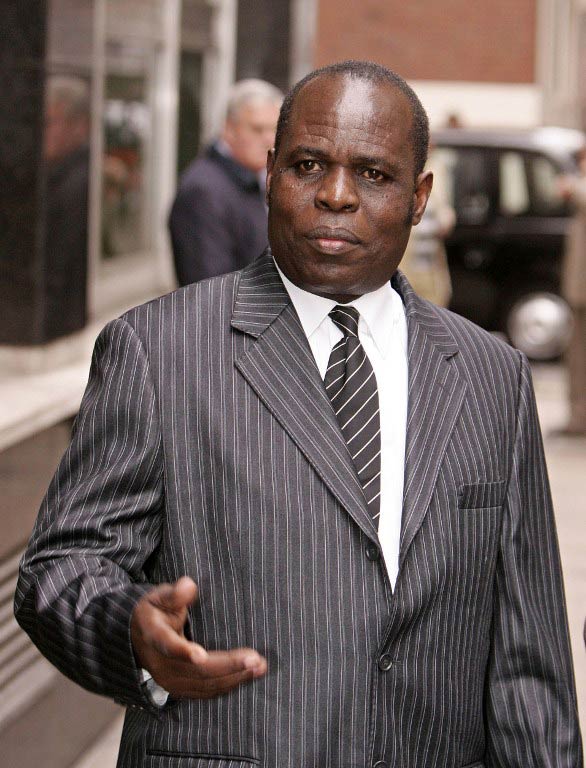

But the gold prize for the miracles business goes to Kenyan Archbishop Gilbert Deya, who was previously based in Peckham, UK. The evangelical pastor who has been photographed with European royalty, prime ministers and presidents engineered a miracle babies scam, claiming to be able to make infertile women fall pregnant. British women travelled to Kenya to “give birth”, but were actually given babies that the pastor and his wife Mary had stolen or abducted. Suspicions were raised when a woman claimed to give birth to three ‘miracle’ babies in a year, prompting an investigation. DNA testing also revealed that there was no genetic link between the women and the babies they’d apparently given birth to.

Mary was eventually arrested in 2004 for stealing a baby from a Nairobi hospital and passing it off as her own. She is currently in prison for child-trafficking. Deya was arrested in 2006 in London and has since been fighting his extradition from the UK to face charges of child theft in Kenya. He has denied the charges, but this particular quote stands out – of course, it was all God’s idea: “I have been judged by the media as a child trafficker, which is a slave trade, but miracles have happened. God has used me and I tell you God cannot use a criminal. They are miracles.”

Given the numerous scams orchestrated in the name of God, it’s no surprise that a generation of young Kenyans is becoming increasingly sceptical about religion. However, it’s a pity that there are still plenty of desperate and ignorant Kenyans around to keep the Jesus Inc industry flourishing.

Munene Kilongi is a freelance writer and videographer. He blogs at thepeculiarkenyan.wordpress.com