Senegalese patients with advanced cancer have been suffering with severe pain due to morphine shortages in the country. Human Rights Watch investigates why.

Senegalese patients with advanced cancer have been suffering with severe pain due to morphine shortages in the country. Human Rights Watch investigates why.

The Central African Republic is in danger of becoming the world’s latest failed state, with increasing sectarian violence sparking a humanitarian disaster. Médecins Sans Frontières’ Dutch general director, Arjan Hehenkamp, has recently returned from the country. He sent this harrowing report:

I’m just back from Bossangao, a town of 45 000 people 330km northwest of the capital, Bangui. From the air, you can see tin rooftops and big compounds, and it looks like a prosperous and bustling regional centre. But then you start looking for people and you see that there’s no one there – all the houses are deserted. Most of Bossangao’s inhabitants have gathered in a church compound, an area the size of nine football pitches, where 30 000 people are enclosed by their own fear.

The country has been gripped by violence since the coup d’etat in March, and religion is becoming a part of the conflict – basically everyone is scared of being targeted by everyone else.

The church compound is like an open-air prison. People don’t even dare to go and fetch the wood they need for cooking. They don’t dare to go out of that protected zone back to their houses – where they would have a roof over their heads and some proper facilities – even though their houses are sometimes only a few hundred metres away.

When you walk into the compound, you’re faced by a teeming mass of people, and you have to navigate through all the families that have set themselves up there. They’re living, they’re cooking, they’re defecating, all in the same compound, and they’ve been there for three weeks. They’ve recently got some shelter materials, but otherwise they’re living in the open air, surrounded by mud and garbage.

Our medical teams are working in the compound, and we’ve set up water and sanitation facilities. We’re pulling out all the stops to provide them with basic amenities and medical care, but at the end of the day it’s an untenable situation. It’s just not suitable for a 30 000-strong group of people – the risk of disease outbreaks is too great.

There are 1 000 to 1 500 people, also mostly Christians, staying in another protected zone around the hospital – they have slightly more space, but in essence it’s the same thing. And there’s a 500-strong group of mostly Muslims in a school nearby – testament to the religious divisions that have crept into the conflict.

We are working in the church compound, and also in the hospital, with both international and local staff. The hospital provides inpatient, outpatient and surgical services, and is functioning at a reasonable level, but it needs to be cranked up in order to deal with the numbers of patients we’re seeing and the kinds of injuries they’re arriving with – injuries which are quite horrific and difficult to treat.

One of our patients was a man who had been shot four times in the back, and his head had been partially hacked off by a machete. The surgeon tried to sew it back on and save the patient, but sadly he died.

Another was a child from a village outside Bossangao. His parents had tied him to the house with chains because he had diabetes and was prone to running around and having fits. But they lost the key to the padlock, so when they had to flee into the bush they couldn’t take him with them. When they came back he was still alive, but he had been slashed badly across his arms when he held them up to protect himself.

This is the level of brutality and violence that is affecting people, and we are probably only seeing a part of it. Outside Bossangoa, we know there are troops and local defence groups going around and seeking people out, engaging in targeted killing or small-scale massacres. Our teams have come across sites of executions, and some have actually witnessed executions.

The villages along the road from Bossangao to Bangui are deserted. For 120km, there’s no one there – 100 000 people have disappeared and fled into the bush. We can’t reach them, and they can’t reach our services. This is a major humanitarian and medical concern.

Compared to last year, when there was already a chronic humanitarian crisis in Central African Republic, the crisis has doubled, the capacity of the state has vanished completely, and the humanitarian capacity has halved.

There’s an acute need for aid organisations to deploy themselves with an international presence outside the capital, and in particular for the UN to lead the way in doing so. An international presence has a protective effect – I’m pretty sure that if MSF had not been present in Bossangoa, the level of violence and killings would have been much higher than it was.

Since the armed takeover in March, the violence hasn’t really abated. There have been violent reprisals and counter-reprisals. The violence continues, but now it is just more targeted and out of sight.

He could hardly be described as Nelson Mandela’s spitting image, but when the British actor Idris Elba arrived at the South African premiere of Mandela: Long Walk To Freedom on Sunday, there was some of the awe and adulation usually reserved for the great statesman himself.

“You can see the sweat! No pressure?” joked Elba, feeling the heat of countless camera phones as he wiped perspiration from his forehead. “South Africans love their Madiba and it’s a massive responsibility to bring him alive in the best possible way.”

Playing Mandela is an acting Everest that stars including Morgan Freeman, Danny Glover, David Harewood, Terrence Howard, Clarke Peters and Sidney Poitier have attempted to scale, but none, perhaps, have quite reached the summit. Elba, who grew up in Hackney, east London, has already earned the praise of Mandela’s family.

Asked on the red carpet about the daunting task of nailing Mandela’s accent, Elba replied: “I just wanted people to recognise him when they heard the sound and say, ‘That’s Madiba!'”

The star of The Wire and Luther had almost missed the black-tie event in Johannesburg after he suffered a severe asthma attack on a South Africa-bound plane and was hospitalised. But he took another flight just in time to witness in person how South Africans judge his portrayal of the nation’s father figure in the £22-million biopic.

The premiere was held a few miles from the suburban home where Mandela (95), remains in a critical condition after spending three months in hospital with a recurring lung infection. “He’s probably watching this on the news as we speak,” Elba mused. “This is very special.”

Mandela’s absence made it a poignant gathering of his closest family, friends and comrades who mingled with their cinematic counterparts. Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, his second wife, sat beside Elba during speeches at a champagne reception. Greeted by ululations, she told the hundreds of guests: “I’m just as excited as all of you are. Thank you for coming to join us in revisiting that turbulent journey that brought us here today. I have no words to describe the translation that Anant [Singh, the producer] came up with of that painful past.”

She added: “Let us just all go and sit back and revisit our history. The importance of this is that we should remember where we come from and that this freedom was hard earned and it was won at a very heavy price. We’re here to celebrate not only comrade Madiba but all the men and women who perished in the liberation war.”

Mandela’s third and current wife, Graca Machel, was also present but declined to be interviewed. They were joined by the new British and US ambassadors, the Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer and long-time friends of Mandela including Ahmed Kathrada, a fellow prisoner on Robben Island, and the lawyer George Bizos, who defended Mandela from a possible death penalty half a century ago. “It brings back the memories,” Bizos said.

Singh said a smiling Mandela had asked “Is that me?” when he saw a picture of Elba made up with grey hair and wrinkled face and wearing one of his trademark Madiba shirts. “I said, Madiba, you really think it’s you?” Singh recalled.

Elba sat through more than five hours of makeup before filming began, said Singh, who spent 16 years on “a very rocky road” searching for funding, the right script and the right director. For the latter role he eventually settled on Britain’s Justin Chadwick, who admitted: “I was resistant. I’m from Manchester, I’m not from South Africa.”

Winnie is played by another Briton, the Skyfall actor Naomie Harris, but the rest of the cast are South African. The film traces the life of the anti-apartheid hero from his childhood in the rural Eastern Cape to his imprisonment on Robben Island and his election as the country’s first black president in 1994.

Mandela’s daughter Zindzi, who attended a previous private screening, said: “When I watched the movie it was a very emotional moment for me. I found it quite therapeutic. It made me confront many emotions that I’d buried and refused to acknowledge. Honestly it was very difficult … At the same time, the love that kept the family together comes through in the film. And the fact that my father left … and my mother continued the struggle.”

The 53-year-old added: “There is a scene where my sister and I are left alone at home because my mother has been locked up and my sister is looking after me, like trying to make us breakfast and so on. It made me weep and weep because it was so true. And we had those moments of loneliness where we found there is nobody for us and it was very bleak and no hope of anybody coming to our rescue. And just that scene alone took me to the various episodes in my life where I just felt the absence of a father, of a mother and of a normal family life.”

In a recorded message for the event, South Africa’s president, Jacob Zuma, said: “A life of inspiration. That is the best way to describe Madiba … He became an inspiration to the world as a freedom fighter, a statesman and a man of principle.

“We will tell the story of this wonderful human being, this great African for many, many generations. We are privileged to have lived in the time when he put his stamp on history. So I welcome the premiere tonight, the first public showing on African soil, of the film Long Walk to Freedom.”

The biggest cheer of the night was reserved for Elba when he joined other cast members on stage and said: “What an amazing turnout, we’re very proud. This story is so much bigger than me, than any of us, and when we were given the task to bring this story to life it was under the guidance of Justin and Anant. I’ve never worked with such a committed set of actors. In true spirit, these are my comrades.”

The movie will be released in South Africa on 28 November and the UK on 3 January.

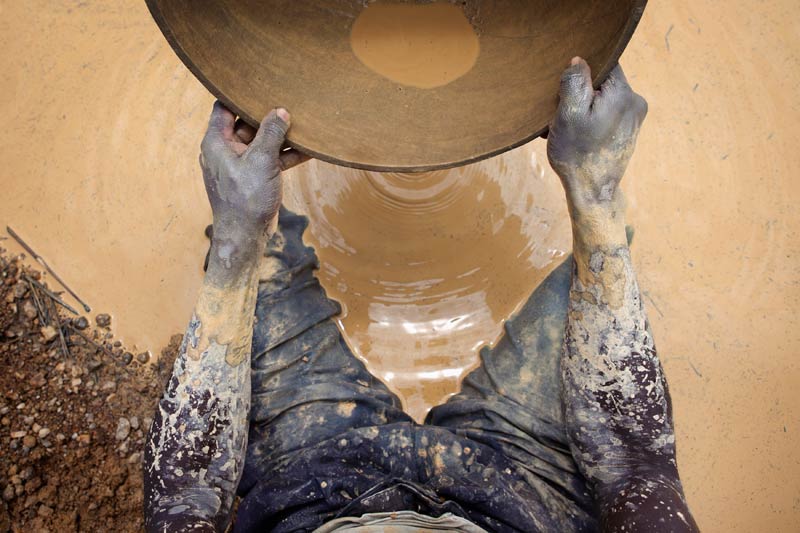

The face of Lydia Madhoro (25) is dusted red from soil as she and her three female colleagues take a brief lunch break. They have been working since dawn on their gold mine in Zimbabwe’s Mashonaland Central Province.

Their hand-dug shaft has reached about 10m in depth, and their conversation revolves around estimates of how much they will make from a pile of gold-bearing excavated rocks. The ore still has to be taken to a miller about 15km away to be crushed, after which it will be mixed with water and mercury to separate out the gold.

Truck operators who transport the ore charge them US$50 a ton, and casual labour used for the loading demand $10 for the same quantity. The millers charge a fifth of the gold obtained.

“We are at work almost every day of the week, going underground for the ore. This is extremely hard work that has been associated with men for a long time, but we are now used to it. We have to do it because, as single mothers, we must feed our families,” Madhoro told IRIN.

The four women formed a syndicate in 2011 to acquire their 0.8-hectare claim near Mazowe, about 50km northeast of the capital, Harare. Madhoro and her partners are certified gold miners and sellers from the mining town of Bindura, about 40km away. They paid about US$1 200 for the registration, prospecting licences from local administrators and surveyor’s fees.

In a good month, they make as much as $2 500 from the mineral, which they sell to the government-owned Fidelity Printers at $50 a gram. The money is divided among the partners in equal shares after paying the millers’ fees and transport costs; the proceeds have so far been used to build basic housing.

“Even though we are not yet making that much money, the good thing is that we have stood up as women to fend for ourselves. We are actually doing better than some men, and I am proud of the fact that I single-handedly feed my twin daughters and can afford money for their primary education, clothes and other basic needs,” Madhoro said.

Breaking barriers

Zimbabwe’s economic malaise, now more than a decade old, is seeing women take on work that has traditionally been deemed the domain of men. Madhoro and her colleagues’ mining enterprise is far from unique, she says. She is aware of numerous women-owned and operated mining syndicates in the province, in districts like Bindura, Shamva and Madziwa.

Eveline Musharu, president of the 50 000-strong NGO Women in Mining, which helps women start mining ventures, told IRIN: “Women are breaking the barriers by venturing into mining, an industry that is dominated by men. There are tangible gains for women who have joined the sector as small-scale miners, especially in gold and chrome, as they can afford household nutritional needs, pay school and medical fees, and even afford some modest luxuries.”

The national NGO was established in 2003, and its members are mainly drawn from the ranks of the rural poor, the disabled, widows, single mothers and those living with HIV and Aids. Musharu said women are turning to mining as an economic lifeline because, given the vagaries of the climate, subsistence farming is no longer a guarantee of putting food on the table.

Madhoro’s route to mining began when she became pregnant by a teacher, dropped out of school and gave birth to twins. Her parents disowned her, and she went to live with her grandmother. When her children were six months old, she became an illegal miner. One night, after digging for gold along the Mazowe River, she was nearly raped by a group of other illegal miners; after that, she tried to make a living as a hawker. Then she learned about Women in Mining.

When she approached the NGO for advice on how to enter the mining sector, the organization suggested she form a women’s syndicate before applying for a prospecting licence. She chose her three partners because they were already friends and stayed in the same suburb in Bindura.

Boosting incomes

The six-year-old Zimbabwe Women Rural Development Trust (ZWRDT), which has more than 500 members and operates mainly in the Midlands and Matabeleland provinces, also helps women get a foothold in the mining sector. More than 100 members of the organization are miners.

ZWRDT director Sarudzai Washaya said 35 of the members, all of whom had previously worked as illegal miners, had been coached to enter the sector legally, and have seen their incomes grow as a result. According to Washaya, mining legally has several advantages, including eliminating the risk of being arrested and having one’s minerals confiscated. Legal miners are also guaranteed of a formal market where they are safe from thieves.

“There is a lot of keenness on the part of rural women to get into mining as they realize the opportunities that the sector offers. Chiefs and district administrators help our members identify and obtain mining claims, and ZWRDT facilitates the acquisition of prospecting licences, and prospective miners pay a joining fee of $20,” Washaya told IRIN.

“We have realized that it is important to build confidence in women, [showing them] that they can perform just as well as, if not better than, the men who dominate the mining sector. In some cases, the women are now employing men, and a few have even managed to buy luxury cars,” she said.

Capital often out of reach

Accessing capital for mining ventures remains one the biggest obstacles for women. Mining equipment, such as compressors for milling ore and pumps to drain water from mine shafts, are generally unaffordable, and women miners have to resort to renting equipment at high costs, eroding their profit margins.

Virginia Muwanigwa of the Women’s Coalition in Zimbabwe, a national NGO for the advancement of women, told IRIN: “Because our society is dominated by men, it is difficult for women to produce collateral when approaching banks. They don’t have title deeds to land, especially in rural areas.”

She said, “If well supported, women can use their involvement in mining to fight the many livelihood vulnerabilities they face. Women miners can benefit a lot from a revolving fund that the government and donors can help establish and from which they can borrow, as banks are unwilling to lend them money.”

The lack of equipment makes mining an even more arduous occupation. “Some of the women have given up on mining because of its high demands and gone back to face poverty in the villages. There is need for the government to give us support because, currently, we are struggling to sustain ourselves in mining,” Washaya said.

The Last Fishing Boat, a film by Shemu Joyah, is about the clashing of cultures when a white tourist makes sexual overtures to a Malawian woman who is the third wife of an illiterate but proud fisherman.

Shot on the shores of Lake Malawi in Mangochi last year, the film recently won yet another prize – this time at the Silicon Valley African Film Festival in California . It picked up the award for the Best Narrative Feature Film.

Earlier this year The Last Fishing Boat bagged the Best Soundtrack award at the Africa Movie Academy Awards, where it received five nominations.