We Kenyans are always in a rush. Life in this country is an unending quest to make that extra coin or stretch the available one in our booming economy. Consider the situation three years ago when Kenyans were constrained by the rising global prices of fuel and maize, the national staple food. The price of maize flour squeezed hard at the already empty pockets of slum dwellers, who responded in the popular Unga revolution street protests.

While urging the government to reduce the price of maize flour from a high of 120 Kenyan shillings (around R12) to 30 shillings (R3), slum dwellers invented the “kadogo“ – or small – economy to stretch their fast-depleting resources. Not only could they now afford three square meals on less than a dollar a day, but the country’s manufacturing industry followed suit.

In the kadogo economy you get to eat according to the amount of money you have. With one rand, you can slurp on steaming bone soup and a mound of ugali, a cake made of corn. A dish of sardines costs nine shillings (50c) and for the same amount one can afford cooking fat. A spoon of sugar costs a shilling (11c), tea leaves are doled out in ever smaller packs for the same amount. Margarine, detergents, soaps, and candles, are halved and quartered to ever smaller amounts that range from a few grams to a hundred grams. “Fifty bob” – 50 shillings or about R5 – would be enough for three square meals a day. Manufacturers have taken note of the kadogo economy and these days even shops in middle class neighborhoods stock products in medium, large, and tiny packs.

Kenyans also noticed that sending money to friends and relatives using Western Union, MoneyGram, and the national postal service was costly. We skirted around this problem and bought phone credit instead, then sent it to the receiver who would convert the credit into cash from the nearest shopkeeper, who earned a small commission. It’s how the world’s first and most successful mobile money transfer system, Mpesa, was born. Every year billions of dollars are exchanged on the platform.

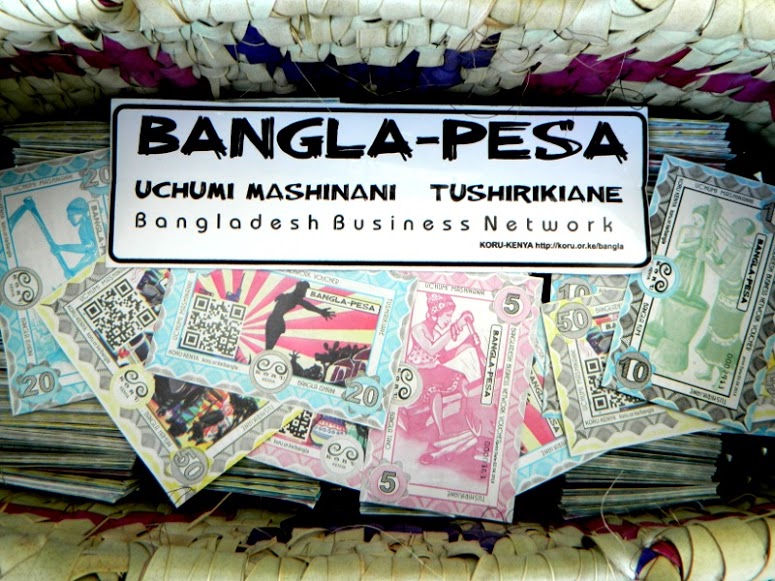

Judging by the numerous civil servant salary strikes, we have landed on the hard times yet again. In a country blessed with entrepreneurial zeal and ingenuity it came as a surprise when the government last month arrested five officials of a group that had found a solution to its neighborhood’s economic woes. The destitute residents of the sprawling Bangladesh slum near the coastal resort of Mombasa, a place where jobs are scarce and the Kenyan shilling is uncommon, introduced Bangla-Pesa (“Bangla-money”) as an alternative currency.

Informal currency

Bangla-Pesa is a voucher or promissory note, which can be exchanged for cash or services at a later date. The system has been seen as an effort to strengthen the economy of the informal settlement.

For instance, a bicycle operator may have the capacity for 20 customers a day, but in general only has 10. He can give rides to other people in exchange for Bangla-Pesa, which he can trade for goods or services – like tomatoes or a haircut – that another Bangla-Pesa vendor may offer. This increases the overall efficiency of the market and helps the community during tough economic times.

Some 200 businesses have agreed to accept the currency, and in return, each has been awarded a credit of 400 Bangla-Pesa. These credits circulate among registered members only. Bangla-Pesa charges no interest on transactions and its membership comprises 75% women, who live below the poverty line and run their own small businesses. Participating businesses include laundries, tailors, builders, salons, and people providing mechanical, electronic repairs and farming services.

In June, six members of the initiative found themselves guests of the state, and were held in police cells for three days. They were initially jailed on suspicion of being members of a secessionist group. When this was found not to be the case they were charged by the Central Bank of Kenya with forgery for holding a printed voucher. The penalty? A possible seven years in jail.

One of Africa’s top investment bankers, Jimnah Mbaru, rubbished the accusation, saying on Twitter: “Bangla-Pesa is just a promissory note liquidatable at a later date. It is discountable in the secondary market. It is not illegal.”

In fact no one has ever been arrested for using Bangla-Pesa’s predecessor, Eco-Pesa, which was formed in Kongowea in 2010, to help clean up trash in the crammed settlement whose dense population lacks the infrastructure to dispose of trash and sewage. Local youths were paid five Eco-Pesa for each trash bag they filled and deposited at the nearest landfill. They then spent this cash at local businesses to buy goods and services from other local sellers or exchanged it for shillings. After three months of using Eco-Pesa, the monthly income of businesses in Kongowea rose by 22%, and the settlement rid itself of 20 tonnes of trash.

Now tongues are wagging among Nairobi’s chattering class that the financial institutions are leaning heavily on the government to come down hard on the Bangla-Pesa founders and members because they fear the alternative currency may appeal to the masses who are daily looking for a way to escape the excruciating high interest rates charged by banks.

In August, the director of public prosecutions dropped all charges against the Bangla-Pesa group members on the basis that they have not broken any Kenyan laws. They are currently waiting for the Central Bank to release their confiscated vouchers and for the government to officially recognise the programme.

In the meanwhile, the 12 000 inhabitants of the Bangladesh slum will have to continue hustling, hoping for an opportunity to make an extra coin or to stretch the ones they have.

Munene Kilongi is a freelance writer and videographer. He blogs at The Peculiar Penguin.