Recently, a Kenyan friend and I had a long conversation about the objectification of women’s bodies in our respective countries, and the role of popular culture therein. As with all cultural industries, there are many avenues for such sexist expressions. But we eventually got stuck on the music sector, and two offerings in particular.

Hers was a song, Fundamentals, by a Kenyan musician known as Ken wa Maria. In the song, he points at the woman he is cuddling up to – even pointing to her nether regions at some point – and states quite authoritatively:

“These are the things,

These are my things,

These are your things,

These are the fundamentals.”

Apparently her body and its composite elements are “the things”, and these things are his before they are hers, or anyone else’s. These are the fundamentals!

In turn, I shared a Zimbabwean song from the late 90s. Called Special Meat (need I really say more?!), the singer engages in Job-like wailing as he exhorts the listener to help him with locating some ‘special meat’. Yes, special meat, like the kind you go into a butchery to buy.

There is a hilarity about these songs. As we watched and shared them online, we couldn’t help but laugh; the sort of laugh that finds these artefacts ridiculous and incomprehensible, and yet pervasively and dangerously catchy.

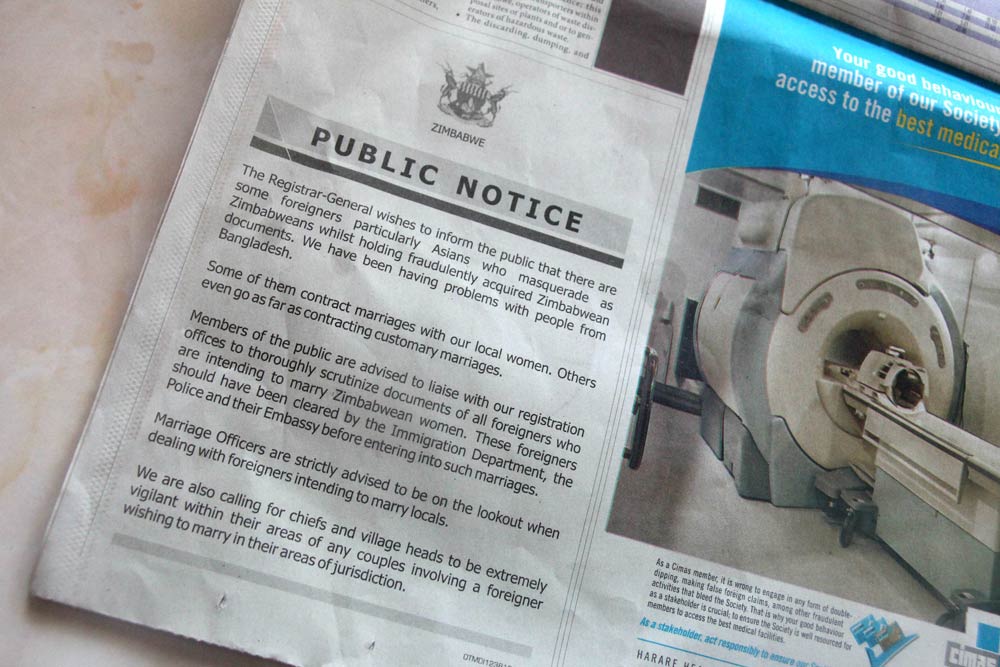

I am thinking of this interaction for a few reasons. Chief among them being an equally ridiculous and incomprehensible public notice featured in one of Zimbabwe’s main newspapers last week.

Nestled on the last page of the business section of The Herald of Wednesday March 26 is a notice – from the Registrar General – which advises that there are “… some foreigners particularly Asians who masquerade as Zimbabweans whilst holding fraudulently acquired Zimbabwean documents…” and that “Some of them contract marriages with our local women.” Members of the public are therefore duly advised to “thoroughly scrutinize documents of all foreigners who are intending to marry Zimbabwean women”. Chiefs and village heads are also called upon to be “extremely vigilant”.

The xenophobic sentiment is enough to rile one up. But the authority of possession in referring to Zimbabwe’s women as a commodity of the state is disparaging and infuriating, to say the least.

The same Registrar General’s office, with Tobaiwa Mudede at its helm, has been the cause of much consternation to Zimbabwean mothers. The Guardianship of Minors Act, a piece of legislation granting guardianship rights and decision-making authority to a child’s father, has seen many mothers struggle to get basic documentation, such as passports, for their children owing to the fact that the Registrar General and his office have been known to make demands that the child’s father be physically present to sign accompanying forms on behalf of the child. A mother’s authority has not been deemed adequate.

The adoption of Zimbabwe’s new Constitution, however, now prohibits discrimination between men and women in terms of guardianship of children. Ironically, voting in this constitutional process took place a year ago in March. And yet a year later, we have notices from the same Registrar’s office reminding us that women are incapable of decision-making of any sort and are in desperate need of monitoring and surveillance; for our own good, of course.

This is not new, however. Zimbabwe’s Legal Age of Majority Act, passed into law in 1982, meant that for two years after Zimbabwe’s independence, women over the age of 18 were regarded as minors in issues such voting and ownership of property. In the same era, an operation to clear the streets of the capital city, Harare, of sex workers and vagrants was brought into force by the state. During this period, the government invoked emergency powers to detain women deemed to be ‘suspicious’’ At that time, over 6 000 women, many of whom were not part of the target group (for example, teachers, nurses and domestic workers), are thought to have been detained and/or arrested.

Walking in the suburb of the Avenues, sometimes nicknamed the red light district of Harare, after dark often still earns a woman an encounter with the police. And walking through town in a mini skirt – or any other form of clothing deemed inappropriate – still leads to women being publicly undressed and heckled.

State control is still set to full volume regardless of the raft of laws that seem to suggest otherwise.

Landmark ruling

The second reason I think of my interaction with my Kenyan friend is Mildred Mapingure who, in a landmark ruling by the Supreme Court of Zimbabwe last week, has had her appeal for compensation for a 2006 rape – that resulted in the birth of a child – partially allowed.

Mapingure is said to have sought emergency contraception within 72 hours of the rape to prevent pregnancy. The police, however, delayed her application. Furthermore, the doctor overseeing the rape case is reported to have been unclear about the difference between a termination of pregnancy and emergency contraception.

While Mapingure’s pregnancy could have been avoided altogether, continual mishandling of her case meant that she was unable to have a medical abortion which is supposed to be provided for victims of rape as per the nation’s Termination of Pregnancy Act.

Indeed, Mapingure’s case is a watershed in the fight for justice, but it is also a chilling reminder of how the state continues to fail women. Whatever peace Mapingure may have made with the ordeal she has had to endure, the fact remains that the state’s lack of urgency and professionalism deprived this women governance over her body, and her future.

With international women’s month coming to an end yesterday, I am angered by the state’s continuing inability to handle women’s issues with the respect and fairness that they deserve.

These instances show a lack of confidence in women’s abilities to make reasoned decisions about their lives and aspirations, orienting our role in society to that of children. From the state and its paternalism to the sexist but body-jolting music we listen to, women are continually relegated to being viewed as objects and subjects.

April dawns today. On April 18, Zimbabwe clocks another year of independence.

Whose independence it is not, though, remains quite clear.

Fungai Machirori is a blogger, editor, poet and researcher. She runs Zimbabwe’s first web-based platform for women, Her Zimbabwe, and is an advocate for using social media for consciousness-building among Zimbabweans. Connect with her on Twitter.