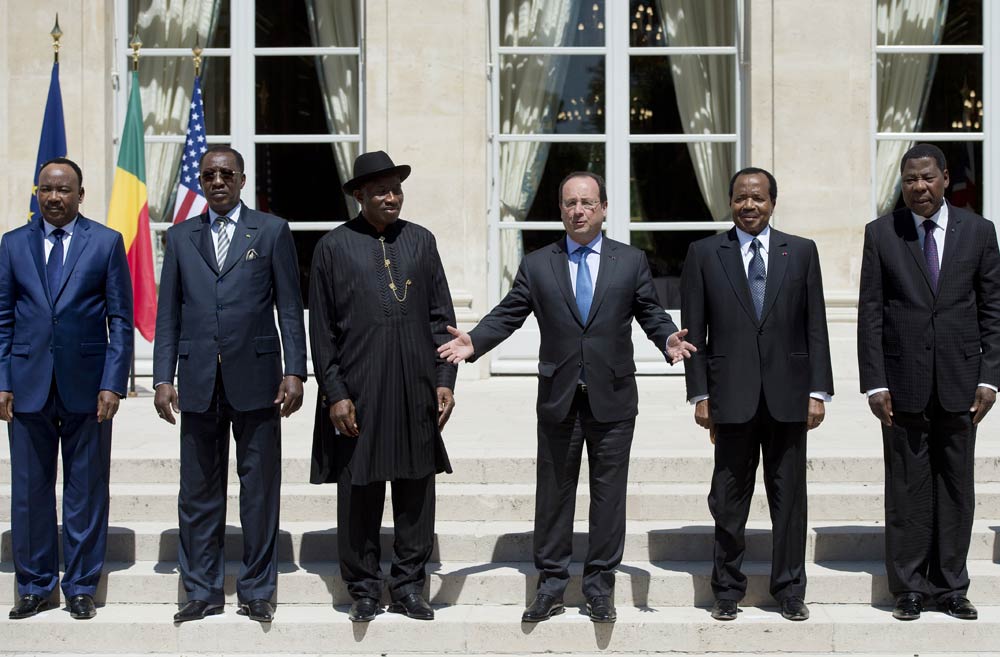

“We’re here!” This is what is embodied in the statement that African nations, in particular West African ones, made when they declared war on Boko Haram at the conclusion of a security summit in Paris. Nigeria and neighbouring countries are to share intelligence and border surveillance in order to track the group’s movements.

African states have finally come to the party – they’re late but at least they have arrived. It was already discouraging that it took this long for our leaders to heed the call. How could Britain’s plan to tackle Boko Haram be released with more force and precision than an African one?

Technically, the fight against Boko Haram should be a Nigerian-led, African-supported initiative with the West providing a helping hand. This was the idea that emerged from the summit – the European Union, the UK and the United States would support the regional effort. When little British girls go missing in Portugal we don’t have Ghana stepping up to the United Kingdom, saying “Steady back, we got this”. When the Malaysian Airlines plane went missing we did not have anyone calling Tanzania’s president, saying “See, thing is we have this little Boeing 77-200ER that seems to have vanished…”

Your problem, your rodeo.

But alas it is not the case here.

The deputy chairperson of the African Union has called for a united international force, citing terrorism as a new phenomenon and one that needs a multi-lateral approach. This is in fact code for “USA and UK, let us borrow some soldiers and technology”.

US troops and intelligence officers have been sent to Nigeria to aid in the search for the missing girls and it is Americans who are analysing the video released by Boko Haram. They have also sent manned planes and drones within the area. The British plan consists of sending military advisors.

It seems that even before this new plan, countries outside Africa were giving a little bit more than ‘support’.

This was the decision taken during a summit held in Paris by French President Francoise Hollande (the same country siphoning extraordinary amounts of resources from its ex-colonies).

The United Kingdom is to host the follow-up meeting to review the action plan.

So Africa is to lead the endeavour when we could not even organise the venue and snacks to come up with the plan? Why was this meeting not held at the African Union headquarters or somewhere else on the continent?

Again, we are in that precarious position where we want to be the life of the party but end up just turning up late, slightly drunk and dancing awkwardly in the middle of the room.

The Nigerian army has gone from blunder to blunder since the start of this debacle, initially claiming that the girls had been returned when they hadn’t and then having to recant the statement. Even western allies have expressed reservations, saying there is a concern surrounding the Nigerian state’s inability to provide decisive leadership to the military. The Nigerian government has also previously stated that they will not use force to get the girls back, and also backed out of talks to have some of the girls released.

Reservations about Nigeria’s efficiency are also shared within the country. Senator Ahmed Zanna of Boko, in a television interview with Al Jazeera, said he was disappointed in the Nigerian government who, despite having been given 1.2-trillion Lira since 2012 and having a lot of resources, has handled the situation badly.

In light of all this we now have the Global North stepping in. But the question is: do we really need this level of hand-holding?

South Africa has advanced weapons (this is a country that used to have a nuclear weapons programme), Ecowas has boots on the ground, Nigeria’s force includes 20 000 troops and aircrafts. Kenya is fast-gaining knowledge on counter-terrorism due to its own hot mess called al-Shabab.

I am pretty sure we can cobble something solid together if we put our minds to it and the West can simply add a little flavour to an already complete meal, not provide all the ingredients.

This should have been the conversation at the African Union HQ at the beginning of the crisis in April:

Goodluck Jonathan: “We have lost some girls, this is a travesty! It cannot be allowed.”

Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma: “Let me rally the troops.”

Other members: “We are on it.”

Paul Kagame would slowly swap his glasses for prescription aviators, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf would tie her bandana tighter, someone else would cock a gun while Miriam Makeba played in the background.

Yes, it sounds like a script from a Justice League comic but the truth is we need superheroes and not sidekicks when we face situations like this. The above conversation between African leaders unfortunately didn’t take place, and what has happened is far too little a bit too late.

As a continent we cannot keep being late to our own party, feigning incompetence and coming up with half-baked resolutions. When situations like this arise on the continent, we need to say “We got this, thank you”, not sit back and depend on outside help when we have the capabilities. There are more than 200 girls still missing. We need to stop being reactive and be proactive. Having summits in Paris and meetings in London and releasing the odd statement is clearly not working to curb Boko Haram and bring our girls back.

Kagure Mugo is a freelance writer and co-founder and curator of holaafrica.org, a Pan-Africanist queer women’s collective which engages in activism and awareness-building around issues of African women’s identity, experiences and sexuality. Connect with her on Twitter: @tiffmugo