Is Christianity African?

This question came to my attention while encountering a recent article on The Africa Report that drove me into a rage. Truthfully, it was not the report so much as one sentence that riled me up, which was:

“Following the US’s endorsement of same-sex marriage in June this year, many Ghanaians have expressed resentment at the practice, describing it as un-Biblical, un-Christian and, therefore, un-African.”

I tweeted the last portion of this excerpt, the part where the logic of this assertion is revealed, and asked Twitter users to tell me what’s wrong with this sentence.

The majority of answers mimicked my own thoughts. People did not hesitate to point out that “un-biblical, un-christian and therefore, un-African” was an oxymoron, wrapped in a riddle, served on a plate topped with hypocrisy in a restaurant called Ignorance.

I could not agree more. The idea that African culture and Christianity could be considered inseparable, struck me as just plain wrong. But what was even more wrong to me, was the reality that in many parts of Africa where Christian missionaries had carried out prep-work for European colonialists, there was a large group of people who

seriously believed that Christian practices had become their culture.

I was still picturing Christianity as this completely Western institution that was carried in on boats and slave-ships not that long ago. I could not fathom the mixture of Christianity and African culture ever being anything but unnatural.

I knew that culture is an evolving thing, constantly absorbing new beliefs and ideas until the customs of ancestors are unrecognisable to descendents. I accepted this premise under the condition that the new beliefs would have to rise organically – whatever that meant – from the imaginations of the people that formed the communities.

Upon further reflection, this struck me as odd. I thought back to all the non-Botswana African people I’d known throughout my childhood. Having attended English medium schools for the entirety of my education, and having been terrible at Setswana by virtue of having a foreign mother, my childhood was rife with a plethora of international friendships. Friends from Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Ghana, Rwanda littered my childhood and perhaps inspired the earlier sparks of pan-Africanist sentiment that would light a fire in my belly throughout adolescence.

But when I went to their homes, or had their families visit mine, one thing stood out as a unifying factor. Despite having different “home languages,” different tints to their browness, different kinks to their fros, they had one thing in common that I’d known for sure then, but somehow forgot as I got older.

They were all seriously Christian.

Some history

When I googled “Christianity in Africa,” I expected to get results that were a mixture of “ancient” history (the beginning of the Ethiopian Orthodox church, one of the world’s first churches in the 4th century) and news on the bizarre church stories of our time (eg. pastors making congregants eat grass), and I did. But I also got an opportunity to reflect on the space in between.

Instead of dismissing this new idea because of the few centuries in between, where African practices were crushed and Christianity was introduced as a precursor to colonial oppression, I realized I might gain far more by realising that most African Christians did not do this.

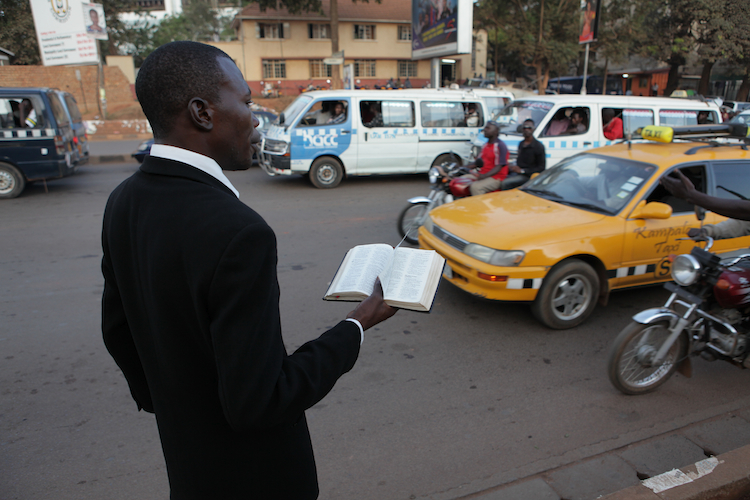

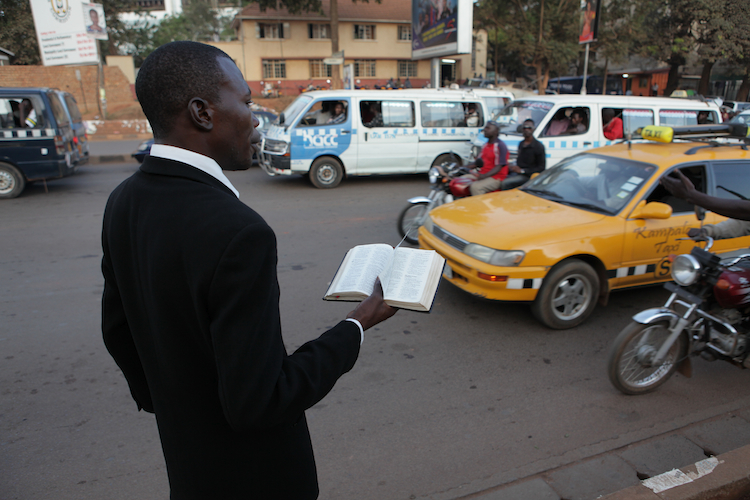

The average African Christian does not exactly walk around thinking himself a product of cultural domination. He considers his faith as organic as I do the earth. It is natural to him to believe in the Christian God, and, like many Africans, he sees no evidence – besides the whiteness of the Jesus statue in his church – that Christianity was anything other than his all along.

I always thought this strange, as well as an opportunity to tout my victims-of-white-brain-washing horn into the ears of whoever would listen. But then I found out that, according to David Barrett, most of the 552 000 congregations in 11 500 denominations throughout Africa in 1995 were completely unknown in the West.

I was introduced to the term “African initiated church” and started to make connections in my mind that I should have been making all along. Africans had been “taking back” Christianity for decades and I hadn’t even noticed. I had remained stuck in my simple-minded box, still thinking of African culture in terms like BC (before Christianity) and AC (after Christianity) where the latter signified death to me.

I was refusing to see all the contradictions and hypocrisies I’d noticed in African Christians as the formation of a new Christianity. I too had been taking part in cultural trivialisation by refusing to see African culture as a living, breathing, complex thing that would not forever remain in the animal-skins and tribal-dancing of our ancestors. Our beliefs and customs hadn’t died, they’d just found new ways to live in Christianity.

How else would one explain the ZCC?

The ZCC

If you live in Southern Africa, there is a chance that you are aware of the existence of one of the largest churches on the continent. Walking through the bus station in almost any city south of DRC, you are likely to encounter women in robes and intricate scarves covering their hair and men in military-esque khaki uniforms; or at the very least, plain-clothes people with a star-badge on their chest.

These people are part of the ZCC: Zion Christian Church. Although it traces its origins to the Christian Catholic Apostolic Church in Zion, the ZCC has been a symbol of African Christianity for decades. This church has been able to take in Africans into the Christian faith without beating their identities out of them.

It is a church that has been difficult for academics to understand, and indeed for many Africans to understand – particularly Africans who, like me, had a very limited fundamentalist idea of Christianity as a Western notion. But the people of ZCC have managed to make the practice of Christianity a lifeline of their previous lives.

The drinking of holy teas and the laying of hands as a healing methods can all be traced back for centuries into histories of African societies.

The ZCC is just one of thousands of “African Indigenous Churches” that were formed by ‘black prophets’ who wanted to give Africans an alternative to the crushing anti-black sentiment of European denominations.

So what if Christianity is African?

If Christianity is African then I’m stumped. I’m outsmarted. I can no longer argue against African Christians on the basis that they worship alien ideologies. I can no longer turn my nose up at African church-goers as sheep ignorant of their bloody pasts. I can no longer dismiss the beliefs of those that don’t agree with my politics because of Christian scripture.

I am stumped.

I can’t even call them hypocrites any longer: accuse them of picking and choosing which scripture they follow, because being denominations separate from the West means Africans are free to emphasise what they wish as being Christian.

How can I point out their acceptance of infidelity and corruption while taking such a harsh stance on homosexuality? How can I ridicule them for their fringe groups eating grass and licking hair for healing?

How can I ignore that many of the parts of African Christianity that offend me are the African parts? Can I continue to blame the ghosts of white Christians when Africans claim that mini-skirts are offensive? Can I continue to conjure up the spirits of European colonisers when Africans assert that homosexuality be punished by death?

If Christianity is now African then we have nobody to blame but ourselves for our failings. We can no longer look to our colonial pasts and claim that bigotry, hatred and oppression are Western inventions. We can no longer look at pastors who take advantage of poor Africans as a continuation in the centuries-long tradition of Western institutions crushing African lives.

We can no longer ignore the fact that if Christianity is now African, so is the oppression we subject one another to.

That’s what it would mean if Christianity is African.

Siyanda Mohutsiwa is a 21-year-old mathematics major at the University of Botswana. She is currently slumming it in Finland. Follow her on Twitter: @SiyandaWrites