“These days, the language of death

is a dialect of betrayals; the bodies

broken, placid as saints, hobble

along the tiled corridors, from room

to room. Below the dormitories

is a white squat bungalow, a chapel

from which the handclaps and choruses

rise and reach us like the scent

of a more innocent time.”

These are the opening lines of Hope’s Hospice, written by Ghanaian-born Jamaican poet Kwame Dawes. He is among nearly 400 African poets from 24 countries in 14 languages who can now be heard reading their work via mobile phones – a first for Africa and the world.

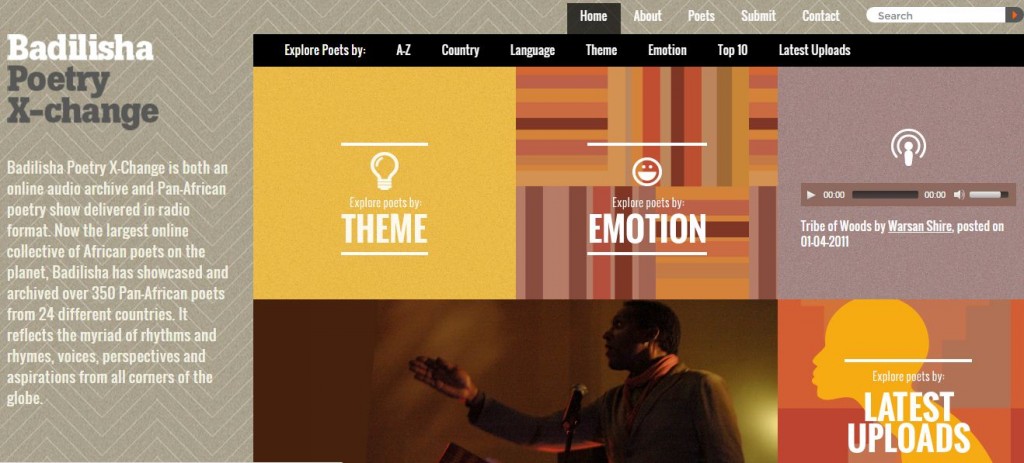

The mobile site, accessible on smart and feature phones, has been launched by the Badilisha Poetry X-Change, the biggest archive of audio recordings by African poets in the world. It is a significant step on this“mobile first” continent where, with limited landline infrastructure, most people access the internet through their phones rather than on computers.

Linda Kaoma, project manager of Badilisha, based in Cape Town, South Africa, said: “We realised we weren’t achieving our goal of reaching a whole audience in Africa. We’ve created a mobile site that can be accessed on almost any phone you have. The response has been great.”

Badilisha appears to suggest Africa’s ancient tradition of oral poetry sits more comfortably in the 21st-century technology of the podcast than in mainstream publishing. Kaoma said: “A lot of publishers are not publishing poetry, but it does not have to be confined to books. It’s alive. The voice adds texture, adds a different layer to the poems. A lot of people are enjoying listening to poetry rather than reading it. We need to change the way we present ourselves to audiences, and audiences need to be aware of different ways of receiving poetry.”

Badilisha began life in 2008 as an annual poetry festival in Cape Town featuring poets from all over Africa and the diaspora. The website came four years later from a desire to reach listeners and readers across the continent, and preserve the work for posterity.

Kaoma said: “If you look at Europe it’s very easy to find archives of many things but in Africa, because of a lot of history and culture was passed down by the oral tradition, and there was lack of documentation, that’s not possible. We didn’t want history to repeat itself.”

The site, which has about 3,000 visitors a month, was relaunched last October with new features such as guests’ top 10 poets and mobile access. It represents a much-needed boost on a continent where performance poets can be found in large cities but few have hopes of publishing a collection in print.

Kaoma said: “The poets love it. It’s a great place to come and reflect and see what other poets are doing. I think there is value in being influenced by someone in the same context: you don’t have to change yourself to be recognised. You can be African and write about whatever you want to write about.”

The 29-year-old said her education was dominated by Shakespeare and she only started encountering African poets when she became involved in Badilisha. She now gives poetry readings internationally. “It’s great to travel to Ghana and Kenya and find a poet writing about what I want to write about. We’re not as one dimensional as people paint us to be. We’re very diverse.”

Badilisha’s poets include 169 from South Africa, 33 from Kenya, 27 from Nigeria, 26 from Zimbabwe, three from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and one from Somalia. Among the 16 African poets in the UK is Lemn Sissay, of Ethiopian descent, who was commissioned to write for the 2012 London Olympics. He can be heard reading his work The Queen’s Speech.

Each poet has a page with photograph, biography and poems in text and audio.

Only a handful of dead poets have been archived so far but there are plans to expand this in coming months, using either a relative of the poet or an actor to perform the readings. Badilisha has two full-time staff and is funded mainly by the Spier Wine Farm in Stellenbosch, near Cape Town, along with some government support.

Among the writers featured is Mbali Kgosidintsi, 31, from Botswana, who can be heard reading I Stand Between My Africa and Me. She said: “They really are pioneers. They are publishing poetry online and creating an African network. It’s a high standard of poets and the fact I can refer someone to Badilisha, and say I’m published on the site, is great.”

The site has triggered debate about the health of poetry in Africa. Kgosidintsi, who has taken part in an African poetry festival in Beijing, China, said: “People definitely want to perform poetry but I worry that the fact that we don’t publish it, and when we do publish, we don’t sell.”

Another poet on the site, South African Natalia Molebatsi, told the eNews Channel Africa: “We can’t say it’s mainstream and we’re not really trying to make it mainstream. All we’re doing is trying to share our work. Remember, it is one of the most ancient art forms. This initiative has given me an opportunity to express myself and share my work with other people.”

David Smith for the Guardian Africa Network