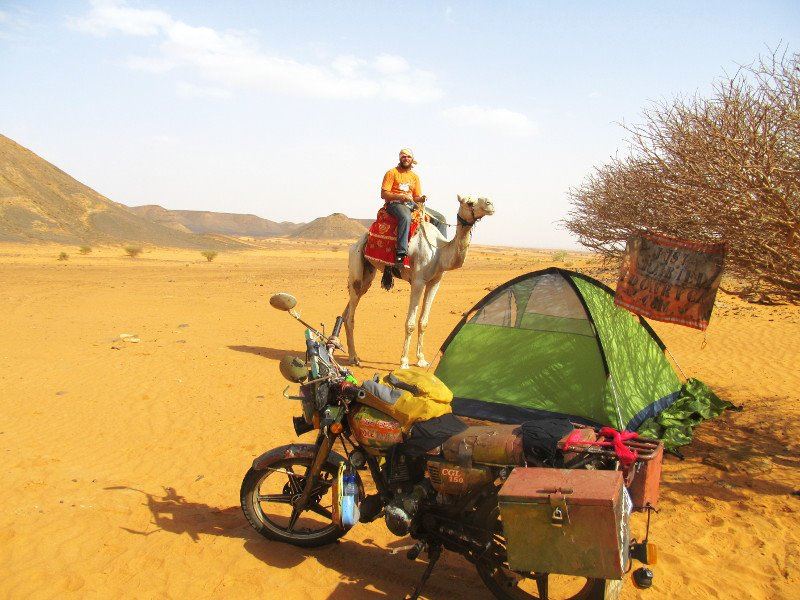

In Paul Salopek’s first year of his trek across the globe, the reporter walked alongside his camels for days in Ethiopia without seeing glass or bricks or any other signs of modern humanity, ate a hamburger on a US military base and was shadowed by minders in the Saudi desert. He has only 32 000 kilometres to go.

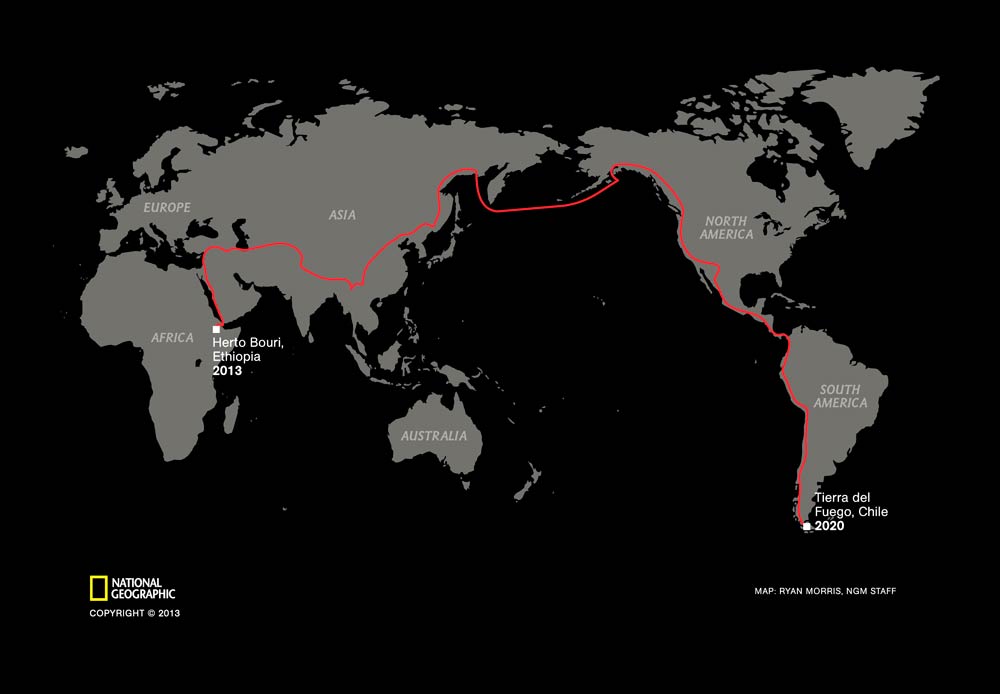

Salopek is walking from Ethiopia to Chile, a seven-year journey that aims to reproduce man’s global migration. Beauty and difficulty filled his first year, which is now nearly complete. In his second he will skirt the violence of Syria but will cross Iraq and Afghanistan.

After about 2 100km on foot, Salopek has walked through five languages (Afar, Amharic, Arabic, French, Somali), filled 40 notebooks full of words, said goodbye to four camel companions and has logged one 55-kilometre day.

Beginning in Ethiopia’s Rift Valley, where early man lived, Salopek walked east into Djibouti, where he ate a hamburger on a US military base, then waited nearly six weeks – because of insurance requirements over piracy attack fears – for a boat to take him over the Red Sea and into Saudi Arabia.

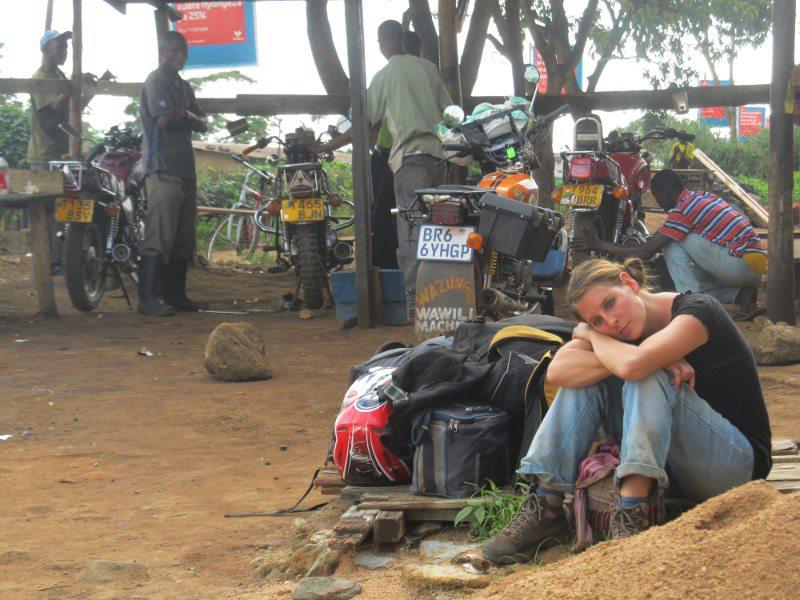

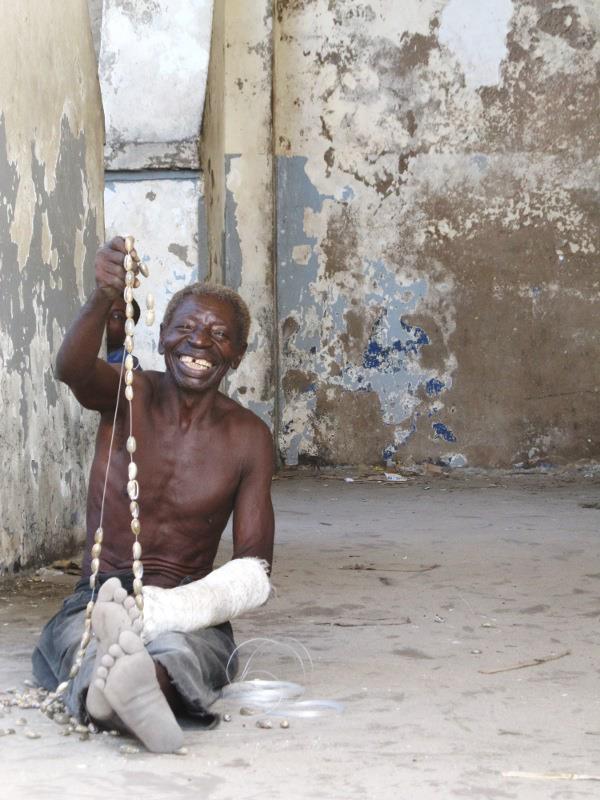

Much of Africa, the 51-year-old noted, is still dominated by humans who travel on foot.

“The Africa segment was remarkable for its kind of historical reverberations, and getting to go through historical pastoral cultures like the Afar, and walking through a landscape still shaped by the human foot,” Salopek said by telephone. “It really has struck me that walking out of Africa, a place that still walks, how fantastically bound to our cars the rest of the world is.”

Salopek’s journey will take him from Africa, through the Middle East, across Asia, over to Alaska, down the western United States, then Central and South America, ending in Chile. That’s about 34 000 kilometres.

The walk is called Out of Eden and is sponsored by National Geographic, the Knight Foundation and the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting. A two-time journalism Pulitzer Prize winner, the American plans to write one major article a year, the first of which appears in December’s National Geographic.

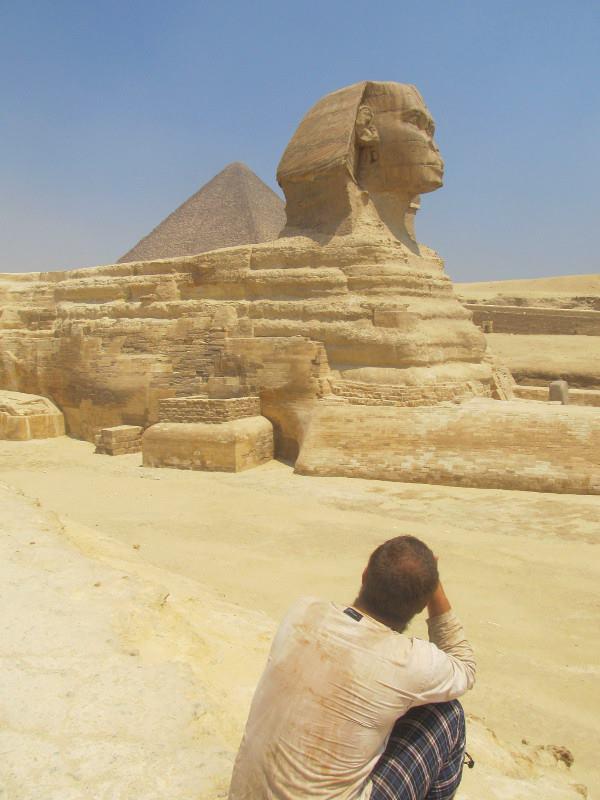

Salopek’s highlight from his first year was his access to Saudi Arabia, a country that maintains tight controls on what outside journalists can see. He noted that the oil-producing nation is 83% urban, a higher percentage than the US.

“I have been moving slowly through Saudi culture, from walking along highways with camels, to the surreal reality of it in some cases is walking with camels by a Pizza Hut with Saudis inside eating pepperoni, who look outside and see a skinny American with camels,” said Salopek, interrupting himself with the observation.

Saudi Arabia made global headlines in October over protests against its effective cultural ban on women drivers. But Salopek encountered many women drivers in the country. “They just happen to be in places where there are no reporters,” he said.

In some places in the country Salopek knew he was being watched by government officials, who explained their presence by saying they were concerned for the American’s safety. But most times he has had unfettered access, he said. He thinks he’s the first outside journalist to walk through Saudi Arabia since 1918.

Salopek doesn’t miss much from the Western world except information because of his limited access to the internet. He also misses his family, but his wife is joining him in Jordan, where he currently is. He says he’s on schedule to complete his seven-year journey, though because of his six-week wait in Djibouti and his boat ride up the Red Sea, he didn’t walk as many steps as he thought he would. He has suffered few physical pains or ailments, save for two blisters.

“This has been very fun and very interesting and I have no indication as I sit that I’m getting bored with it. On the contrary, walking into a new country on foot with your clothes on your back and a shoulder bag stuffed with notebooks was really fascinating.”

Jason Straziuso for Sapa-AP.