The Mail & Guardian spoke to US civil rights icon Jesse Jackson about the challenges facing South Africa’s young democracy.

The Mail & Guardian spoke to US civil rights icon Jesse Jackson about the challenges facing South Africa’s young democracy.

Somalis may soon be receiving letters from abroad for the first time in more than 20 years after a deal was struck with the United Nations’ postal agency – the latest step towards ending Somalia’s isolation following two decades of civil conflict.

But the challenges to bringing the Horn of Africa country back into the global postal community are manifold – there are no functioning post offices, only the main roads are named and most houses do not have a number.

Add to that the ongoing struggle with al-Qaeda-linked insurgents, who still control much of the countryside, and parts of the coastline infested with pirates, and it is clear the UN’s Universal Postal Union (UPU) and its partners have their work cut out.

The Swiss-based UPU said in a statement last Friday that international postal services could start operating again in Somalia within the next few months.

Somalia’s Minister of Information and Communication Abdullahi Hirsi signed a memorandum of understanding with Emirates Post Group this week for Dubai to act as a hub for handling mail destined for Somalia, it said.

The UPU, which brokered the deal, said its 192 member countries could resume sending mail to Somalia once the arrangements were finalised.

About 2-million Somalis live abroad and 9.9-million in Somalia, served by a postal network that is “basically inexistant”, the UPU said, having dwindled from 100 post offices in 1991.

UPU spokesperson Rheal LeBlanc said Somalia had created an office at the airport to handle mail moving in and out of the country, initially to service the government, embassies and universities, “but they seem to have plans to phase in postal services across the country over the next few months and years”.

Hirsi said his country would need help getting the post going again.

“We ask for all means of assistance as we have to start from ground zero,” the UPU statement quoted him as saying.

In the latest sign of optimism that Somalia was emerging from its violent recent past, Britain opened an embassy at Mogadishu airport last week after its previous mission closed in 1991 as civil war broke out. – Reuters

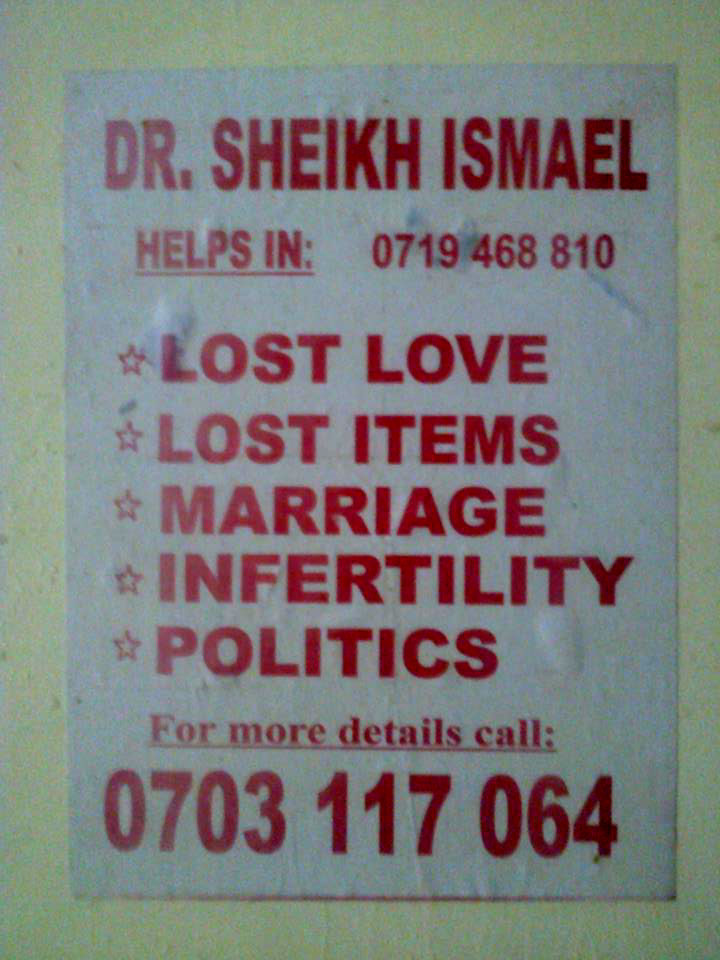

When I first arrived in Nairobi, I saw the signs but didn’t know what they meant. Once I started understanding Swahili, I learned that the profusion of ads, nailed to fences, stuck on poles and printed on A3 paper, were for waganga (witchdoctors) offering assistance mainly in matters of business, money, love and infertility. In just about every suburb of Nairobi, you’ll find at least one ad, hand-painted, on a little plate, nailed high up on a pole. For an average of around 6000 shillings (R600) you can get to see one of these mgangas but it is advisable to avoid those who advertise on paper. They are reputed to be con artists.

There’s a distinct undertow of witchcraft to the interpretation of many unusual events in Kenya. Even Christians, confronted by some unexplained phenomenon, might exclaim “juju!” (black magic) in the middle of the conversation, and usually everyone will agree.

There are two main ‘currents’ of witchcraft practised in the country. The first, often termed kamuti (kah-moo-teh), is attributed to the Kamba people. It is Bantu witchcraft, similar to that known in South Africa and involves the use of charms, ‘muti’ and spells to achieve the client’s ends. This type of witchcraft is heavily traded in the areas of Kitui and Kitale, not far from Nairobi.

The second stream of witchcraft derives from the Mohammedan influences in East Africa – from the Arabs who landed here centuries ago – and involves the deployment of ‘genies’ (as in Aladdin) to achieve one’s ends. It is grounded in texts from the Qur’an and here, you ‘rent’ the services of a genie to fulfil your wishes for you. You can even buy a genie to work for you permanently and exclusively if you have a few hundred thousand shillings at hand. This type of witchcraft is heavily traded in Mombasa, at the coast, and is reportedly common among the Swahili people. It’s even more strongly associated with Zanzibar, and Dar es Salaam on the Tanzanian coast.

Recently, a friend of mine was involved in a minibus accident. She was the only one without a scratch. The makanga (conductor) with a bleeding face wanted know where she got her juju from because he needed some.

Another friend’s sister was victim of a grenade attack at a church in Mombasa. Shattered glass went everywhere but she, standing at the window, was not injured. She said that people were muttering things about the protection afforded by genies. Interestingly, she was at church but had recently converted to Islam, not that anyone knew. Not anyone visible, anyway.

From the Bantu-Kamba kind of witchcraft there’s a tale so oft-repeated it has reached the level of urban legend. It’s the story of an unfaithful wife and her temporary lover who become “stuck” after having sex, like what happens to dogs. Of course, medical science refutes the possibility of this occurring among humans. But it happens – a YouTube video says so.

The clip shows a rather large woman and a rather small guy lying on top of her, unable to do anything to release himself. The woman is covering her face from the peering crowd, and the guy looks terrified. They are eventually released from each other when the husband comes into the room and does something to free them. One can’t see what he does in the video but the stories I have heard mention the uncapping of a Bic-type pen or the flicking of a Bic-type lighter.

Stories of “Nairobi girls” using this kind of witchcraft to secure a man is also legend. This kamuti involves the insertion of herbs or crystals into the vagina to keep the man abnormally attracted and emotionally ‘stuck’. The man will also be unable to gain an erection with any other woman. These kinds of stories are discussed very matter-of-factly in Nairobi. It is known to be a part of the girls’ personal arsenal, and is reputed to be a common practice.

Despite its widespread acceptance in Kenyan culture, witchcraft obviously has it detractors too. There have been horrific incidents of ‘witch’ lynchings – in 2009, five elderly men and women were burned alive by villagers in western Kenya who accused them of bewitching a young boy. Last year, The Star newspaper reported that elders in the coastal Kilifi Country were fleeing their homes out of fear of being killed for practising witchcraft.

Speaking to other Kenyans, mainly from the coast, I have heard stories of genies and what they can get up to if their master is properly paid and clearly instructed on the client’s wishes. I met a guy called Gilbert who told me he was forced to have sex in his car with a work colleague who had a crush on him. His brand new car refused to start and wouldn’t move when he tried to push it. Once he had done the deed with her, it started on the first turn.

During the mayhem that followed Kenya’s disputed election results in 2007, shops were looted and burned. A Mombasa youth grabbed a TV from a shop and escaped with it on his head. When he got home, he was unable to get the TV off his head. He only managed to remove it when he went back to the shop to return it. The clip isn’t on YouTube but millions of Kenyans saw it on national TV.

Skeptics will be wont to dismiss these juju stories as just that: stories. But before you do, let me add my own experience for light reflection: A few years ago, when I was researching witchcraft for a book I was writing, I was referred to an mganga based in Mombasa. He agreed to be interviewed on condition I undertook ‘rehma’ (spiritual cleansing) with him. I couldn’t resist.

I met the mganga at the Nyali bridge, just outside Mombasa. He looked very ordinary, wearing a plain shirt, khaki pants and flip-flops. He took me to a small, corrugated shack in the village of Bamburi. A fire was lit, molasses tobacco smouldered near it and incense was stuck in a banana to attract the genies. Evidently, genies like sweet things.

The ritual involved handfuls of rice sprinkled over me amid chants of a Muslim prayer. A goat was forced to inhale my recollection of negative experiences over a small fire and I was washed down by a live and wetted chicken. Salve (mafuta) was spread on my breastbone and applied to my palate and I left with little packets of sticks and ointment that I was to apply every morning to ward off evil. It took about 20 minutes in all, and I paid the mganga 8 000 shillings (R800) for the privilege. I didn’t feel any different afterwards, but the guy that had introduced me to the daktari (doctor) warned me that rehma would make me become “a magnet for women”. I laughed at the time and didn’t think any more of it.

I don’t consider myself to have any special appeal to women, but let’s just say that for the few weeks after my rehma, I had a torrid time of it all.

Brian Rath was born and raised in Cape Town. He now lives and writes in Kenya, and has a novel due to be published shortly.

Author’s note: Please be cautious of the claims and contacts that are provided in the comments section under this article. Readers have been given misleading information and have lost money. Exercise proper judgment.

After Zimbabwe’s controversial new Constitution was given the go-ahead in the March 16 referendum, the ruling party has intensified its intimidation campaigns across the country in the lead-up to the elections.

Footage obtained by the Mail & Guardian reveals how Zanu-PF propaganda is being used in public: often through a very visible military presence in urban and rural residential areas, and in party meetings where citizens are admonished for considering voting for any party other than Zanu-PF in the upcoming poll.

Human rights groups including the Zimbabwean Peace Project have noted that fears of violence and intimidation in the country are escalating. Last month, prominent human rights lawyer Beatrice Mtetwa was arrested for allegedly obstructing justice, and Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai’s aides were detained after a raid on Tsvangirai’s communications office in Harare. “What we are seeing are signs of fear,” Tsvangirai said in response. “The targeting of my office is reprehensible and is meant to harass and intimidate the nation ahead of the election, now that we are done with the referendum.”

Abundance Mutori was just 14 when he began playing with the other members of Mokoomba. It was in 2002, when they were at school together at Mosi-Oa-Tunya High in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, and he remembers that their biggest problem was getting hold of instruments. “We didn’t have our own, and even at school when we had a music class we didn’t have any guitars or keyboards,” he says. “But my dad used to play in church and had a bass guitar at home, and he first showed me how to play. From then on, I was practising by myself or jamming with the guys.”

Now, in their mid-20s, Mokoomba are being feted as Africa’s most internationally successful young band after a rise that is as deserved as it has been remarkable. After all, they come from a country with an international musical profile that has sadly declined since the glory days of the 80s, largely because of Aids. Even in Zimbabwe they were initially considered outsiders. They sing in Tonga, a language that most Shona and Ndebele speakers can’t understand, and come from a tourist border town that’s a 12-hour drive from the capital, Harare.

The group are signed to a small Belgian label and were unknown in Britain until their second album, Rising Tide, was released there last August. But by the end of 2012, they were featuring in the annual “Best of” lists in publications from the Guardian to fRoots, and so it is no surprise that they should win Songlines magazine’s newcomer award, announced last week. This summer they will be playing at major festivals across Europe, including Womad in Britain.

They succeeded thanks to a mixture of determination, skill and luck. As teenagers, they got most of their experience with the help of a local bandleader, the late Alfred Mjimba, who was “the only guy with musical instruments in the area. You’d go round to see him, and try to play this or that, and if he liked what you did, he’d say: ‘There’s a gig, come and play with us.'” He was no major star, but he played in local hotels and small clubs – though it was initially impossible for Mutori to play in bars because he was the youngest member of the band, under-age, and his parents objected.

The would-be musicians lived in Chinotimba township, a “high-density” area that was first established in the pre-independence zone outside the smarter, affluent one reserved for white people and tourist hotels near the spectacular waterfall. As a border town, close to Zambia, Botswana and Namibia, Victoria Falls was a “melting pot”, according to Mokoomba’s young manager Marcus Gora. “When you were growing up there, you couldn’t escape different cultures, languages and musical influences. There was music from the local Tonga tradition, Congolese rumba and soukous, funk, pop from the Beatles, and even country. That’s what our parents played.”

The band reflects these different cultures. Mutori plays bass, and his bandmates include Trustworth Samende, an excellent guitarist, and the powerful, soulful singer Mathias Muzaza, who travelled widely in southern Africa as a boy with his Angolan and Zambian parents. The band played in restaurants, or busked for tourists, and developed their own distinctive style. “It’s Afro-fusion,” says Mutori. “A mixture of Tonga rhythms, soca, soucous and the other things we listened to growing up.”

Mokoomba broke out of Victoria Falls, and then Zimbabwe, with the help of the non-profit NGO Music Crossroads International, which organises workshops, festivals and competitions in Africa. The band took part in a local competition in 2007, and the following year were invited to the InterRegional festival and contest in Malawi – which they won. Their prize was to record a six-track album, which has not yet been released in Britain, and a European tour.

International success didn’t prove easy at first, but Mokoomba were at least getting noticed. In Malawi they had met Manou Gallo, the bass player and singer from Côte d’Ivoire, best known for her work with Zap Mama. She collaborated with the band at the HIFA Harare arts festival in 2010, then produced last year’s breakthrough Rising Tide. Enthusiastic reviews, and an impressive appearance on Later… with Jools Holland followed.

Now, as the band prepare for a lengthy summer tour, bolstered by their latest award, it seems that Zimbabwean music could enjoy an international renaissance. Of the country’s 1980s heroes, Oliver Mtukudzi is still in excellent form, while Thomas Mapfumo, who lives in the US, returns to Britain next month to play at the Field Day festival. But several of that glorious band the Bhundu Boys have died. “The momentum was lost because of Aids,” says Gora. “A whole generation was decimated, and they were the core of the music industry at the time.”

How do they feel about Robert Mugabe and the political upheavals in Zimbabwe? Gora is diplomatic. “As a band, we have made a conscious decision to build our career outside of politics until a time we are established enough to have an effective voice.”

Mokoomba may be leading the country’s international music campaign, but it has taken time for Harare audiences to appreciate their Tonga-language Afro-fusion, which has little in common with the fashion for the Congolese-influenced Sunguru music of local hero Alick Macheso. But that’s beginning to change, as Mokoomba spend more time living and performing in the capital. “Baaba Maal is appearing with us when we play [at] the Harare festival on May 5,” says Gora. “Mokoomba is becoming a big band.”