It used to be a common joke in Nairobi’s bars, salons and taxis: the fastest way to get rich in Kenya is to start your own church. Now the joke has matured – the surest way to make a quick buck (and dodge taxes) in Kenya today is to open your own creche.

Infant day care schools are springing up at such an alarming rate in Nairobi that they may soon outnumber bars and butcheries in some townships.

During colonial days and many years after Kenya’s independence, it was not common to find black African kids attending preschools in droves. Africans – “natives” – were expected to jump straight into primary school with over-size uniform shorts, rusty brogues and peak caps. The expectation was for one to attain an education fit for the colonial economy (bricklayers, trolley pushers, coffee graders, veranda painters). Creche was a fancy foreign concept reserved for kids of local bankers, lawyers, European expatriates, diplomats and cushy industrialists who had a fond nostalgia of daycare centres back home in London, Berlin or Paris.

This is no more. With the tie-down of education standards and generally relaxed rules, anyone can now open a creche in Kenya without much financial investment. The most sensible requirement is to have to have kids nearby, lots of them. Hence, creches are flourishing in Kibera slum, farming settlements and cluster towns.

A proper classroom is far from being a requirement. Livestock sheds, ancient grinding rooms and derelict garages are being torn down in Nairobi to make way for new creches. Infant meals or proper desks are not necessary either. With stressed and short-on-time parents willing to cough up to 3066 Kenyan shillings ($US35) per child per month, there’s no shortage of cheeky entrepreneurs willing to “renovate” their homes into creches.

“Mine is a creche in the morning, paint room in the afternoon and a bar at night,” says Hakem, a 35-year-old entrepreneur who has 30 kids enrolled at his Thanks Tidings Day Centre in Kibera.

“I retire my furniture, sofas, television, table suites to a kitchen during the day to make way for kids attending creche in my house,” says Sofia Wanari, another creche owner. “At night it’s a proper home again when the kids are gone.” When pressed about how much of revenue she makes, she smiles. “The earnings are pretty juicy. In a month where all parents pay fees I collect about 105 010 Kenyan shillings ( $1200).”

Unlike registered and affluent creches in leafy parts of Nairobi, many springing up in the townships have little regulation. Teachers are not trained or qualified – that’ll be expecting way too much. With steely will, a former kitchen maid, a tobacco clerk or a retired bus driver can turn into a creche school teacher anytime. Curriculums or timetables are neither designed nor followed. One only needs to spend the whole day yelling at infants, minding their general silly tantrums, enforcing sleep times, rehearsing Mau-Mau-era songs and chaperoning them when they stray close to a broken pool or busy road. Not that many parents care: urban Kenyans are tied down in booming factory jobs, office chores and green fruit market stalls, so anyone willing to take care of kids during the day readily finds willing parents.

It’s not entirely unsurprising to see a burger or pizza shop in the evening being dusted and scrubbed to make way for a creche in the morning. An advert on the wall will read: “Sally’s pizza 5pm to 8pm; infant preschool 8am to 3pm”.

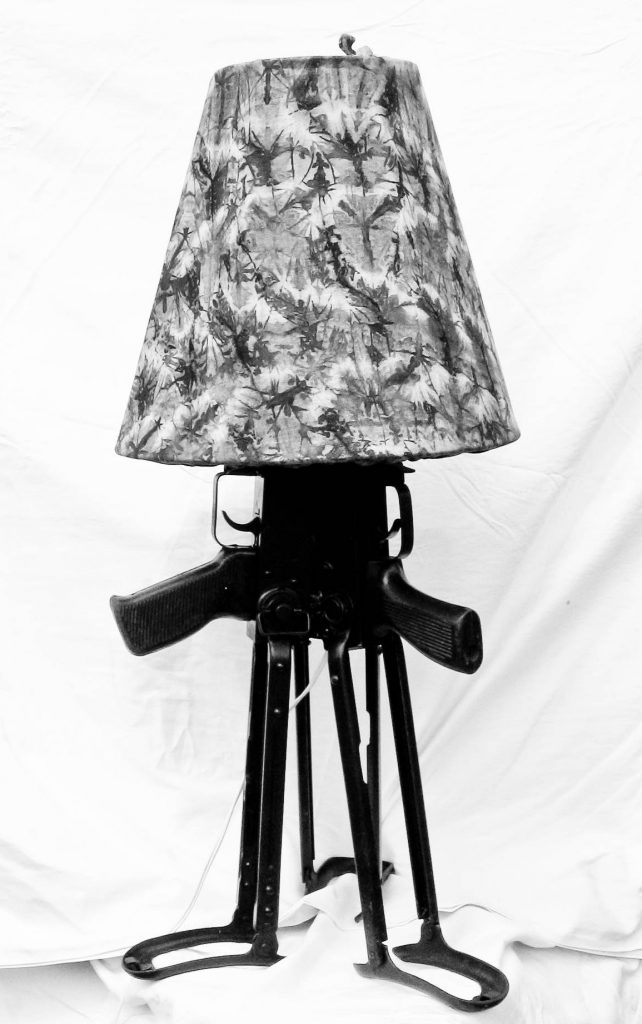

A suitable, safe location is a not a priority for creche owners. It’s not unthinkable to see a creche opening up next to a strip bar, a gamblers’ saloon or a railway crossing. “Greedy entrepreneurs don’t necessarily care about kids’ safety. It’s a mighty shame one way or another,” explained Michelle Gaziki, a special needs education facilitator with the Kenyan education ministry.

Of course these creche owners live with a permanent fear of authorities who often inspect creches for health facilities, licences and building safety. Like in any part of East Africa, an under-the-table ‘gift’ to a government inspector will help take care of any problems.

However, for entrepreneurs like Wanari this business is a win-win scenario. “No one wants to be saddled with a weeing infant during the day when there are jobs to chase in the economy. Those who say unlicensed creches are menacing are simply grumpy middle-class Kenyans used to seeing their children in gated preschools years before primary. It has changed.”

David Gianti is a Kenyan student studying towards a master’s degree in education at the University of Nairobi. Connect with him on Facebook.