Vines stretch to the horizon under the hot summer sun in a vineyard near Casablanca, one of the oldest in Morocco, where despite the pressures from a conservative Muslim society, wine production – and consumption – is flourishing.

“In Morocco we are undeniably in a land of vines,” says wine specialist Stephane Mariot.

“Here there is a microclimate which favours the production of ‘warm wines’, even though we aren’t far from the ocean,” adds the manager of Oulad Thaleb, a 2000-hectare vineyard in Benslimane, 30 kilometres northeast of Casablanca, which he has run for five years.

The social climate in the North African county is less propitious, however, with the election of the Islamist Party of Justice and Development in 2011, and the fact that Moroccan law prohibits the sale of alcohol to Muslims, who make up 98% of the population.

In practice though, alcohol is tolerated and well-stocked supermarkets do a brisk trade in the main cities where there is a growing appetite for decent wine.

According to some estimates, 85% of domestic production is drunk locally, while around half of total output is considered good quality.

“Morocco today produces some good wine, mostly for the domestic market, but a part of it for export, particularly to France,” says Mariot.

Annual output currently stands at about 400 000 hectolitres, or more than 40 million bottles of wine, industry sources say, making the former French protectorate the second biggest producer in the Arab world.

By comparison, neighbouring Algeria, whose vineyards were cultivated for a much longer period during French colonial rule, produces 500 000 hectolitres on average, and Lebanon, with its ancient viticulture dating to the pre-Roman era, fills about six million bottles annually.

Some of Morocco’s wine regions – such as Boulaouane, Benslimane, Berkane and Guerrouane – are gaining notoriety.

Already it has one Appellation d’Origine Controlee – controlled designation of origin, or officially recognised region – named “Les Coteaux de l’Atlas”, and 14 areas with guaranteed designation of origin status, most of them concentrated around Meknes, as well as Casablanca and Essaouira.

And in March last year, an association of Moroccan sommeliers was set up in Marrakesh bringing together 20 wine experts.

French legacy

In the central Meknes region, nestled between the Rif Mountains and the Middle Atlas, there is evidence that wine production dates back some 2 500 years.

But the industry was transformed during the time of the protectorate (1912-1956), when the kingdom served as a haven for migrating French winemakers after the phylloxera pest decimated Europe’s vineyards around the turn of the 20th century.

As in Algeria and Tunisia, the French planted vineyards extensively, with Morocco’s annual production exceeding three million hectolitres in the 1950s.

The main grape varieties used to produce the country’s red wines are those commonly found around the Mediterranean, such as Grenache, Syrah, Cabernet-Sauvignon and Merlot.

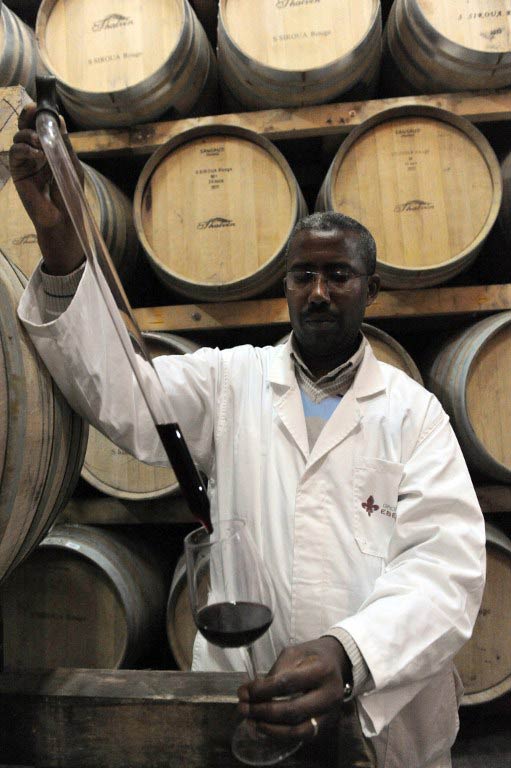

Mariot, the manager of Oulad Thaleb, boasts that the domain, which he says has the oldest wine cellar in use in the kingdom, built by a Belgian firm in 1923, produces one of Morocco’s “most popular wines”.

Standing by a barrel, he casts a proud eye on the vintage, describing it as a “warm and virile wine”.

Abderrahim Zahid, a businessman and self-styled “lover of fine Moroccan wines” who sells them abroad, says the country now produces “a mature wine which we can be proud of”.

Morocco’s wine industry now employs up to 20 000 people, according to unofficial figures, and generated about $170-million in 2011.

But the remarkable progress made by the sector in recent years has taken place within a sensitive social environment.

While alcohol production is permitted by state law, and supermarkets and bars enforce no special restrictions on Muslim customers, officially the sale and gift of alcoholic drinks to Muslims is illegal. They are unavailable during Islamic festivals, including throughout the holy month of Ramadan.

Separately, the Islamist-led government decided last year to raise taxes on alcoholic drinks from 450 dirhams ($53) per hectolitre to more than 500 dirhams.

So far this has not noticeably deterred consumption among Morocco’s population of 35 million, although economic realities certainly influence local drinking habits.

The wine favoured by Moroccans is a cheap red called Moghrabi, which comes in plastic bottles and costs 30 dirhams (about $3.50) a litre.

Comments are closed.