Liberia is getting back on its feet after a protracted civil war that killed over 200 000 people, displaced over a million, and largely destroyed the country’s infrastructure and institutions. After a decade of peace, the European Commission’s Humanitarian Aid Office (Echo) is pulling out of the country, saying its needs are shifting from humanitarian to developmental.

Liberia has indeed made progress, particularly in attracting international investment that has led to steady growth in GDP, and most importantly in maintaining peace. But poverty and unemployment remain rife, corruption is pervasive, and little headway has been made towards post-war justice or reconciliation. In short, significant challenges remain.

IRIN recently spoke to a few key individuals who worked on Echo-funded projects – most of them health-related – during and after the war, to learn how far Liberia has come.

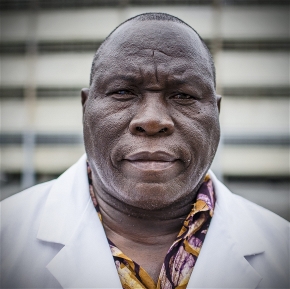

Moses Massaquoi, doctor:

Moses Massaquoi started working with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) after being displaced by a rebel attack in July 1990. He went on to work with the NGO in numerous postings across Africa before returning to Liberia with the Clinton Health Access Initiative (Chai).

“The main challenge in the post-war [era] is a challenge of building the system, from the point of view of having the necessary human resources,” he told IRIN. “So I would say the big challenge is capacity. How do you build the capacity, with all systems broken down – health, education and everything?”

Massaquoi has committed himself to rebuilding a health system left in tatters by the conflict. In particular, he would like to see Liberia producing its own medical specialists.

He says he wants the country “first and foremost, in my own medical profession, to bring back a system of specialisation. We didn’t have control of producing our own specialists. The government had to send people out [abroad], and when they go out, they don’t come back,” he explained.

A sign of progress in this area, he says, is a post-graduate training program currently being established by the government, which will see its first students starting in September 2013.

Barbara Brillant, nurse:

Another former MSF employee currently engaged in medical training is Barbara Brillant, who runs a nursing school in the Liberian capital, Monrovia.

Brillant first arrived in Sierra Leone as a missionary in 1977. “I arrived here [in Africa] as a young lady… with a lot of enthusiasm, and I was going to cure the world and teach everybody. And I ended up here 38 years later, having learned a lot,” she told IRIN.

“It [the conflict] was very, very sad. For me personally, it was scary, no doubt about it. But as a missionary and having lived with the people of Liberia, the sorrow was more seeing the Liberian people in the condition they were in,” said Brillant.

She says she saw both resilience and pride, but also “evil at its worst” during the conflict.

Sister Barbara, as she is known to the 450 students in the nursing school, is concerned that behind Liberia’s current peace there is no true reconciliation. She sees little improvement in the quality of life of most Liberians.

“It’s a pity, because… the hurt is still there, the anger is still there. You can only pray and hope that time will heal a lot of the wounds. They will never ever forget it, that’s for sure… They’re having a very hard time.”

Despite peace, “it’s a difficult place to live in,” she said, with cost of living having risen steadily over the years. “To rent a house now is insane,” she added.

Nyan Zikeh, programme manager:

Like Massaquoi, Nyan Zikeh began working for MSF while himself a refugee. He returned to Liberia in 1998 and has since worked with the NGOs Save the Children and Oxfam, where he is currently a programme manager. He says he now feels the dividends of Liberia’s lasting peace. “What I’m grateful for is that we have peace, and the chance to raise a stable family now exists,” he explained.

His plans for the future are to leave his job and become an agricultural entrepreneur, which he says will create opportunities for others to work, earn a living and learn. “I will still be working in development, but not in charity,” said Zikeh, who is concerned about the dependence being created by Liberia’s current aid culture.

“It is also to let the authorities know that we can make examples, that we don’t have to sell all of our land to very large companies,” he said. Recent large-scale land acquisitions by foreign businesses have been criticised for exploiting local communities and engaging in corruption in the awarding of concessions.

A recent audit revealed that only two of 68 land concessions awarded since 2009 fully complied with Liberian law.

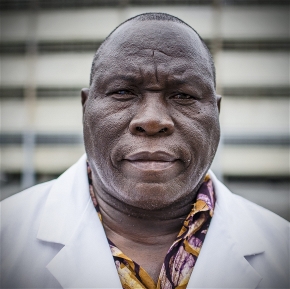

Nathaniel Bartee, doctor:

When the war broke out in 1989, Nathaniel Bartee was a doctor who had just returned from earning a master’s degree in the UK. He started the organisation Merci to deal with the humanitarian situation in Monrovia; it quickly expanded into the provinces.

During the conflict, Bartee was at times separated from his family. “I didn’t want to leave Liberia because of the amount of suffering, and the [numbers] of health personnel were not many. So I stayed to guide a younger generation of doctors.” By the end of the conflict, he was one of just 50 doctors left in the country.

Bartee says there has been clear improvement in the provision of health services since those days. “Today I think health is much better. Most of the health workers have returned, and there are more graduates being produced,” he explained.

But he is concerned that the Liberian government is not sufficiently prioritising healthcare. For this reason, he intends to become a senator to push for increases in the health budget in Parliament.

Ma Annie Mushan, women’s peace activist:

In late 1989, Ma Annie Mushan was, in her own words, “not a woman to speak of”.

“I was just a housewife” she told IRIN. During the war, Mushan was displaced from her village and ended up living in the town of Totota, where she was approached by the women’s peace movement that had sprung up in Monrovia.

Mushan eventually became the leader of the Totota branch of the women’s peace movement, which ultimately played a significant role in putting an end to the conflict.

Like many Liberians, she is frustrated by the slow pace of post-war development. “Even though there is progress, people in Liberia are looking for jobs up and down… There are so many people that are not working in Liberia – not a day. That has been one of the major problems we’re faced with.”

She now works on the Peace Hut project, which emerged from the women’s movement, and seeks to address the problem of gender-based violence, which she sees as one of Liberia’s biggest challenges. Mushan feels the existing court system in Liberia is unable to effectively deal with cases concerning women’s issues.

“My focus will stay on the women, to build their capacity up. I still want to be working for the Peace House [Hut], because it is the Peace House [Hut] that got me where I am today,” she concluded.