Ikram Bash Imam freely admits it is not an easy task to persuade a sceptical world that the “new” Libya, still awash with weapons and rival militias, is a holiday destination worth considering.

There is no question about the pull of attractions: more than 1 000 miles of pristine Mediterranean beaches, magnificent Roman and Greek ruins, palm-fringed oases and Saharan troglodyte caves. And while Libyan cuisine may lack the sophistication of its Maghreb neighbours, the country is remarkably unspoilt.

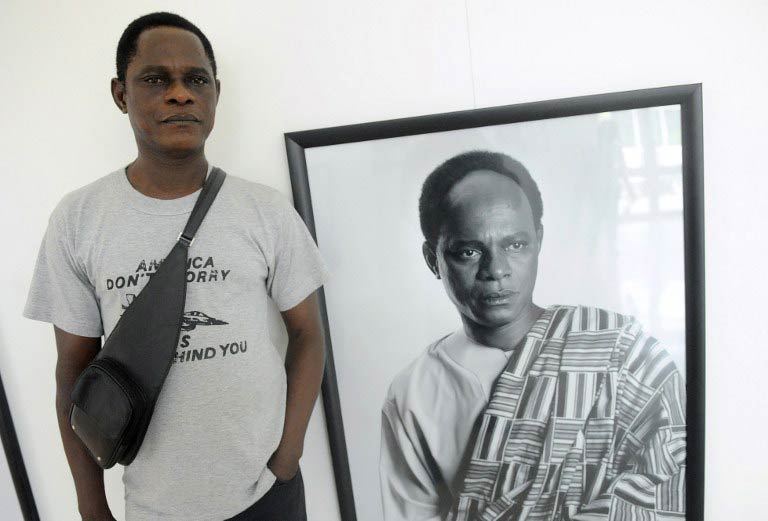

“Libya is a beautiful place and we are a hospitable people and we have much to show to visitors,” says Imam, tourism minister in a government whose prime minister, Ali Zeidan, was briefly, but embarrassingly, abducted by gunmen in Tripoli last month. (“It’s true that this is a very challenging issue,” she says.)

Muammar Gaddafi’s violent demise at the hands of Nato-backed rebels two years ago has left the north African country open to the world for the first time in more than four decades. But the barriers to tourism are daunting: dozens of heavily armed militias, a desperately weak central government, jihadi terrorism and, to some, the threat of state collapse.

The scale of violence is exaggerated by the media, says Imam, receiving visitors and well-wishers at the Libyan stand at this week’s World Travel Market in London’s Docklands, a pulsating mass of laminated-badged industry insiders struggling under the weight of brochures, DVDs and posters.

“Everyone focuses on the violence but most armed clashes are between [Libyan] individuals and groups. It is not a war. When young people can get back to work and the economy is more normal and we have our elections and constitution they will hand in their weapons.”

Sensibly, Imam is taking the long view and moving cautiously. The short-term plan is first to build up domestic tourism and raise revenues to 4% of GDP over the next two years. International tourism comes after that. Diversifying employment away from the dominant energy sector is an important element of the government’s overall economic strategy.

Urgent work needs to be done. The Unesco-recognised world heritage sites at Leptis Magna and Sabratha are still badly neglected, though plans are under way to develop the lush hills of Jebel Akhdar, south of Benghazi, and Jebel Nafusa in the western mountains.

“We have to be realistic and we have to be honest about what we say and promote what we have,” says Imam. “The new Libya will not be closed to the world. We were cut off for too long. We don’t want to have hundreds of thousands of tourists coming without the infrastructure and services to receive them with high standards and in an honourable way. We need to lay the foundations for our industry.”

Libya is not entirely a blank slate. Modest growth began in Gaddafi’s final years, with some niche adventure travel and several spectacular hotels built in Tripoil – including the lavish Turkish-owned Rixos, where foreign journalists were virtually imprisoned during the revolution, and the supposedly secure Corinthia, the scene of Zeidan’s kidnapping. Later this year an international marathon is being held at Ghat deep in the Sahara.

Other practical problems include the difficulty of getting tourist visas from Libyan embassies: in one change, group visas can be obtained by travel companies on arrival. And friendly governments, including the UK, advise against all travel to parts of the country – including Benghazi and Derna – and all but essential travel elsewhere in Libya. The Foreign Office cites “a high threat from terrorism including kidnapping”. It adds: “Violent clashes between armed groups are possible across the country, particularly at night. You should remain vigilant at all times.”

Imam also agrees that Libya’s identity as a conservative Muslim country poses problems for mass tourism from the west. But it should, not, she suggests, be an insuperable one. “When I am in London and it’s raining, I need an umbrella. Yes we are Muslim society and we don’t want to offer alcohol. If people want alcohol they can go elsewhere.

“Our plan is that when you come to Libya you will enjoy the Libyan experience. Libyans are not closed-minded. But visitors must respect the country and its values.”

Libya’s problems are not unique. Nearby stands in the Middle East and North Africa section at the World Travel Market include a large but very quiet Iraqi one – where gaily coloured Beduin carpets and brass coffee pots have no obvious effect on countering the negative impact of Baghdad’s repeated suicide bombings. Tunisia, one of the few relatively bright spots of the Arab spring, is moderately busy. On the Egyptian stand – complete with plaster sphinxes – the emphasis is on Red Sea resorts far from the tensions of Cairo. Palestinians are trying to promote Jerusalem and Bethlehem in competition with Israel.

Lebanon’s stand displays fine wines but is also quieter than usual – tourist revenues affected by the war next door. Syria has not even been represented for the past two years. “There’s no point,” said a glum Arab tour operator. “It’s suicidal to even go there.”