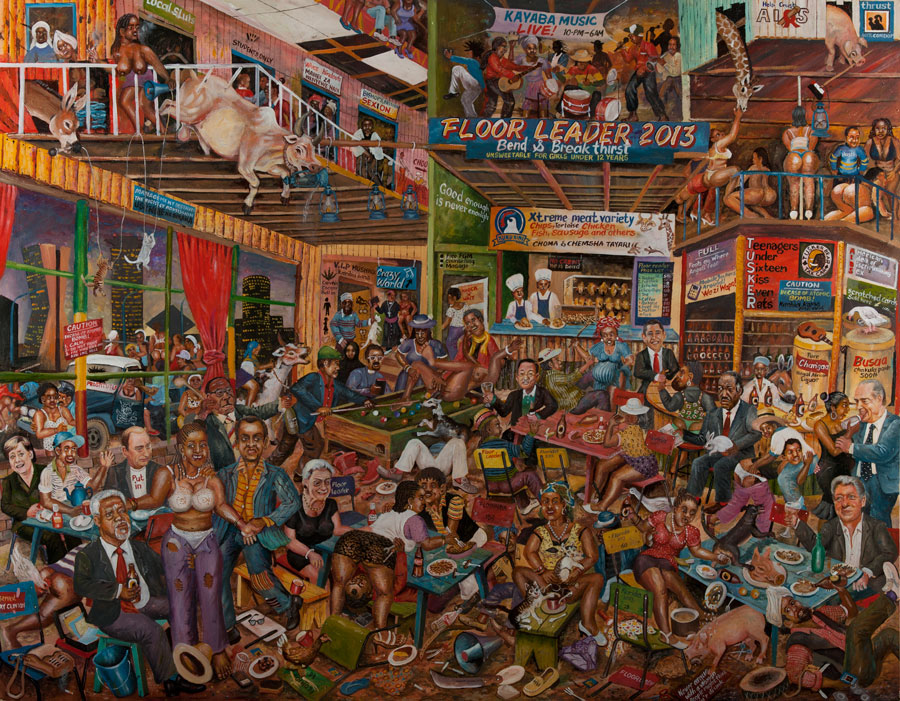

Angola usually appears near the bottom of rankings that quantify the ease of doing business in a particular country. The most recent Doing Business report ranks Angola in 179th place out of 189 countries. Corruption is rampant and institutionalised – Angola is ranked 157 out of 176 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. The costs of opening a business are very high, the entrepreneurial climate is fraught with obstacles, and the bureaucracy is gloriously inefficient.

Despite all this, I left my corporate job in New York City earlier this year and moved back to Luanda to start a business.

Angola is constantly in the news because of its economic boom – ever since the war ended in 2002 and the price of oil, the country main export, has soared, the government has become awash in cash. It even has the apparent luxury of ‘bailing out’ Portugal from its current economic crisis – one just has to look at the amount of Angolan money in Lisbon’s stock exchange. However, the entrepreneurial climate in Angola has struggled to keep up and doing business here is a challenging proposition, to put it mildly.

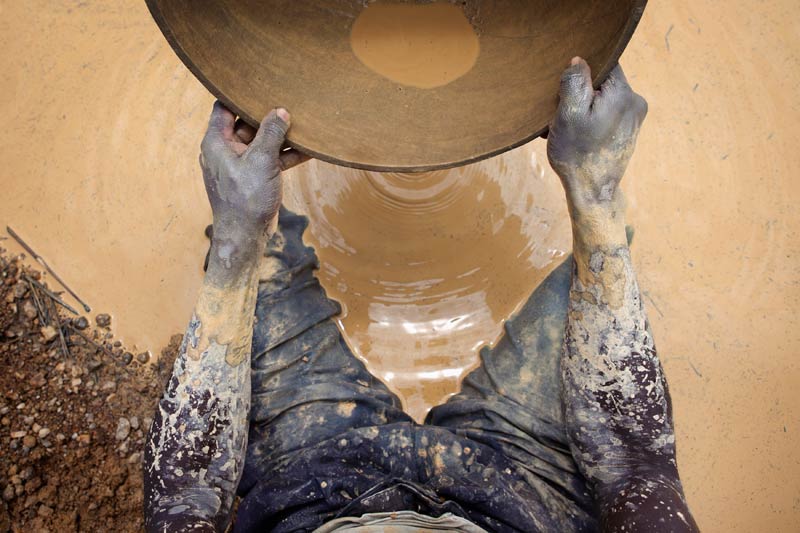

This summer I started an online micro-enterprise in Luanda with two friends. The start-up operates in the hospitality sector, does not have any paid employees, and so far does not yet pay rent in an office. Still, it cost more than $4 000 and took six weeks to open. Even so, this is a great improvement from just two years ago.

Officially, it’s possible to open a business in Angola in just one day at the Guiché Único da Empresa (GUE), a government institution that greatly simplifies the process. The reality, however, is that it takes much longer. But two years ago GUE was not what it is today, and I’ve been able to witness just how much more professional and efficient the institution has become.

Once we had our start-up legalised and our business model prepared, we were ready to start operations and set about finding and contacting potential clients. As any visitor to Luanda will quickly realise, traffic in the capital is an absolute nightmare. If there is ever a study done on just how much Luanda’s traffic negatively impacts the country’s economic output, I’d be first in line to read it. With this in mind, we had to be very creative with how to get the most out of the day, how to meet with different clients in different areas of the city, and how to squeeze in time for a quick lunch. With a bit of finesse, a willingness to experiment, and a very open mind, we learned to adapt our schedules and temper our expectations.

Each country has its own business culture and its fair share of rather quirky norms. When it comes to communication in Luanda, introductory emails are overly formal and people love to give themselves important titles. Their e-mail signatures are coveted, elaborate markers of glory.

Most people have two phones – one SIM from the country’s two mobile phone networks in each. Nothing gets done on Friday and if Monday is a holiday you can expect people to take Friday and perhaps even Tuesday off.

Pray that your workplace is adequately equipped with a proper generator and water supply, because the city’s infrastructure is very weak. If it rains, chaos will ensue. The city’s roads and sewage system are badly built and not equipped for rain, as the water has nowhere to go. The already dreadful traffic worsens and some areas of the city resemble Venice with its canals.

Luandans have learned not to be overly specific with time and know to give generous leeway when it comes to people arriving late to meetings. Sometimes, the situation is simply outside of their control – in our city, anything can happen on the way from point A to point B.

People love to feel important. Often, in order to speak with the head of a company or a member of government you’ll need to write a letter and coax the secretary into letting your unimportant self speak to her almighty boss. On the other hand, a phone call is always better than an email and a lot of importance is given to interpersonal interactions.

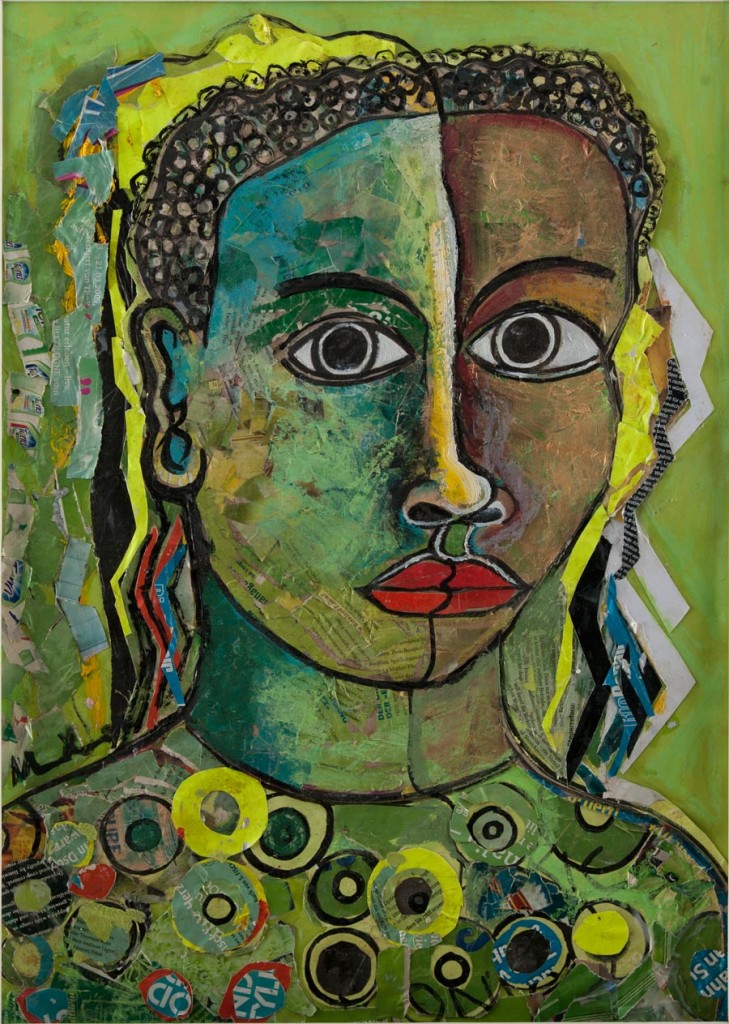

Despite the setbacks and the long list of things that need improvement, the atmosphere in the city is incredibly electric. Money flows and liquidity is high. It seems everyone is hustling, everyone has a side business, everyone has cash money. I get very excited when I see people my age opening their own businesses, acting on their ideas, helping each other out, and generally making a difference, however small.

The most important thing about hustling in Luanda is surrounding yourself with doers and believers – friends and associates who believe in themselves, their ideas and their capacity to help develop this country of ours.

Claudio Silva is Angolan. He has spent time in New York, Washington DC, Lisbon, Reading (UK) and attended university in Boston. In 2009, he started Caipirinha Lounge, a music blog dedicated to Lusophone music. Claudio contributes to several other blogs including Africa is a Country and Central Angola 7311. Connect with him on Twitter.