Andrew Esiebo is a Nigerian photographer whose photo essay, Pride, is an exploration of barbers and their shops across seven West African countries. He captures the spaces in which barbers operate and looks at the aesthetics of their shops.

Pride was recently featured in the New York Times’ online magazine Lens, and ten of his prints have been added to the permanent collection of the Musée du quai Branly in Paris.

Esiebo chatted to Voices of Africa about the barbers, their shops and the hairstyles he shot.

How did the barbershop project come about?

The idea for Pride came about during a street photography project I was doing in Lagos. While photographing people on the street, I stumbled upon a barbershop and started talking to the owner. He said to me that while he might not be considered an important person in the society, he was proud to be the barber to one of Nigeria’s ex-presidents. That resonated with me and made me think about the role, and importance, of barbers in West African society. I thought about the idea for several years and in 2012, following an artistic award I received, I was able to develop the project. I travelled to several West African cities and looked at the relevance, and the role, of the barbershop in the city.

What can you tell us about the role that the barber plays in West African societies?

Barbers help people to gain an identity. Some people have to have the right cut to project who they are. The way they look, through their hairstyle, influences the way they feel about themselves, the way people see them and address them.

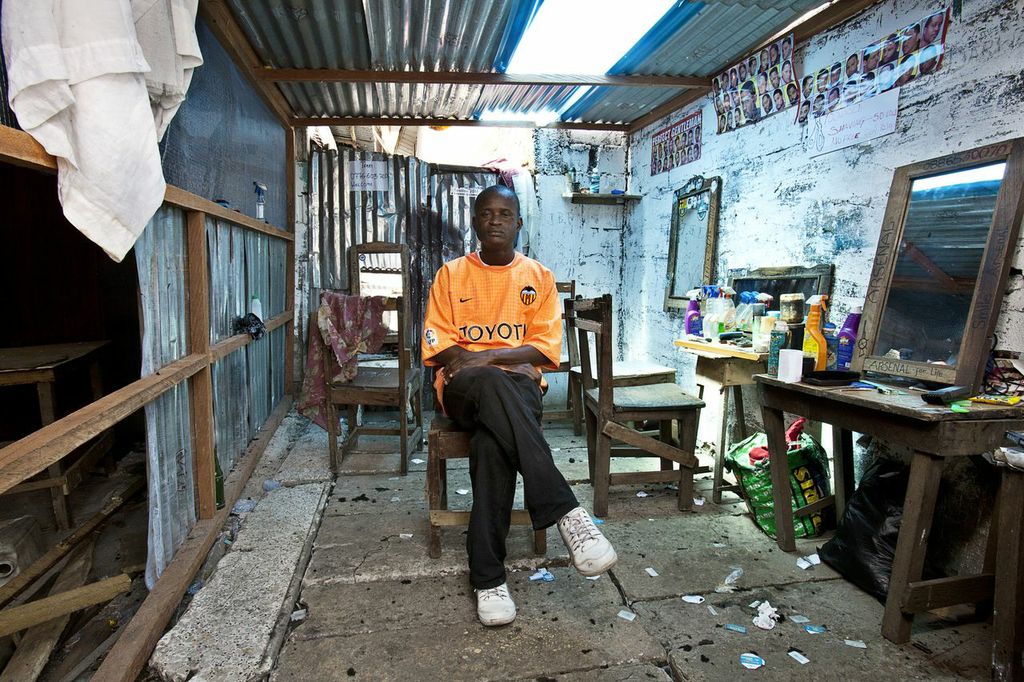

Barbers are also influential because their shops are what I call “public intimate spaces”. People share their problems in conversation with the barber. The barbers learn a lot from this, and this knowledge is then shared with other customers.

So, barbershops are not only a place for cutting your hair but a space where people meet, where they come to relax and discuss issues; a space where relationships are built, business deals are sealed and where intimate subjects are often discussed.

Which barbershops were most interesting to you?

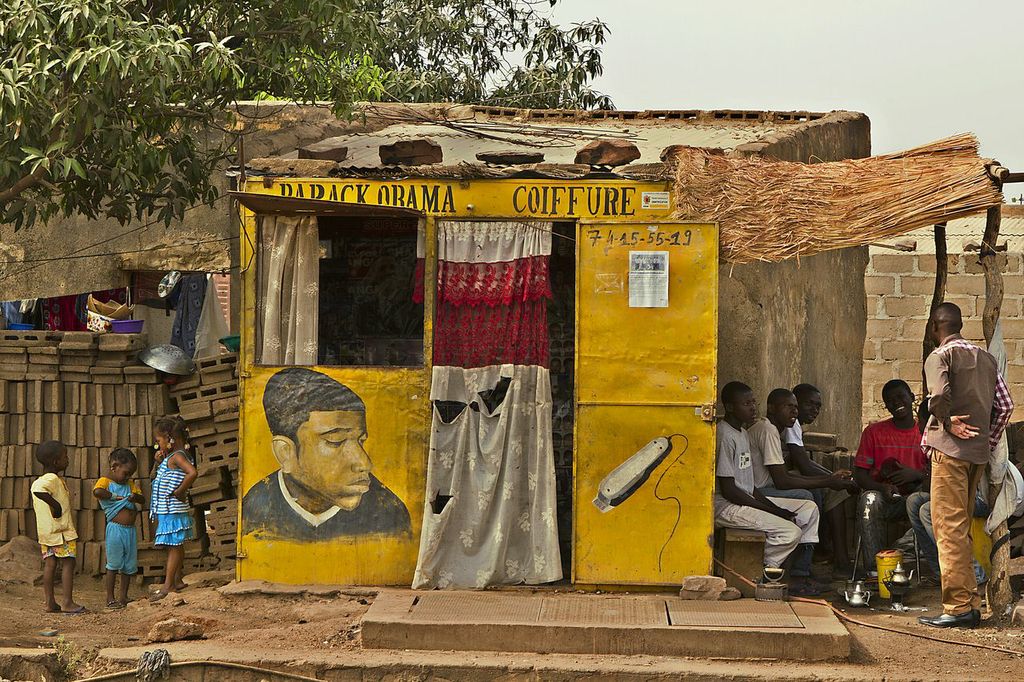

The barbershops I found most interesting were those which displayed icons, religious images, pictures of hip-hop artists, posters of soccer teams and icons of global black culture. There was a shop in Mali where the guy had posters of [Osama] Bin Laden and [Muammar] Gaddafi next to pictures of President Obama. I found this contrasting use of icons interesting. The barber said that, on the one hand, Bin Laden and Gaddafi were his heroes while on the other hand Obama is a global symbol of black power. For a black African to be the president of the US is something to be proud of, he said. So he named his shop Barack Obama Coiffure. There were many others I found interesting too.

Tell us about the hairstyles.

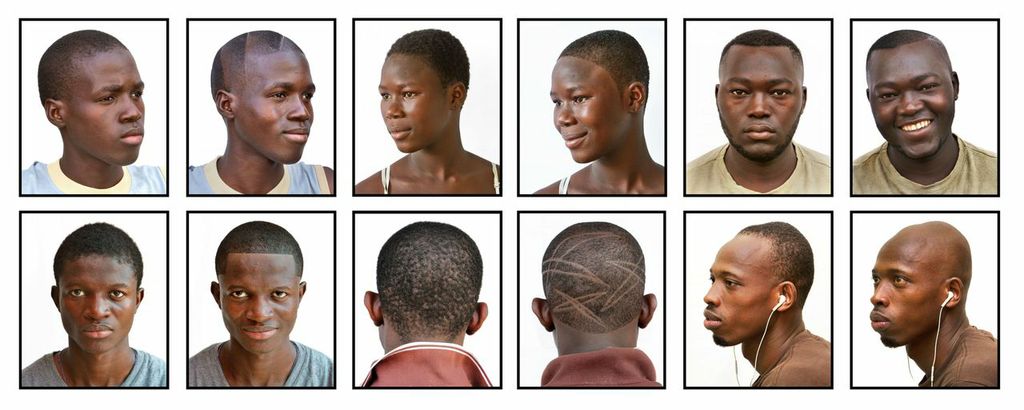

Many of the hairstyles offered by barbers were similar, inspired by football stars or hip-hop icons in America. While the hairstyles themselves overlapped, their functions differed, depending on the country.

In Senegal or Mali, which are restrictive Islamic societies, a hairstyle can be a way of making a social statement, while in Liberia or Côte d’Ivoire, that same hairstyle can be a way to get attention from the ladies.

There was one particularly eclectic one from Senegal, worn by a barber. I asked the guy why he barbered that style for himself. He told me: “You know, this is a very conservative society but through my hair, I have the freedom to express what I want”. I really fancied that. He was rebelling against the conservative nature of the society.

Were there any regional or national differences across the barbershops you photographed?

To be honest, I did not find many regional or national differences in barbershops across West Africa. In fact, I found them very similar. There also was unity in the hairstyles themselves; unity in the language of using your head to talk.

Sure, there were differences in the names of the styles but many of the styles were the same. It shows how globalised or how connected the world is today. Many of the styles come from the same influences: Western media.

Are you exhibiting Pride at the moment?

No, but I hope to exhibit this project across West Africa and beyond. I am still looking for an organisation to support the exhibition. I would also like to publish a book on the project because I think this is an important part of our culture that needs to be documented. It has to be celebrated and shown around the world.

What is your next project?

I will be looking at the nightlife of Lagos and beyond through the eyes and lives of DJs. DJs at parties, DJs in concerts, DJs at various ceremonies. I want to use DJs, who are an integral part of our nightlife, to depict life in Lagos.

Any advice for aspiring African photographers?

I think the only advice I can give is for them to work hard, to be passionate about what they do, to never give up and always be ready to learn new things. Keep pushing and open your horizons. You’ll go places with that.

Comments are closed.