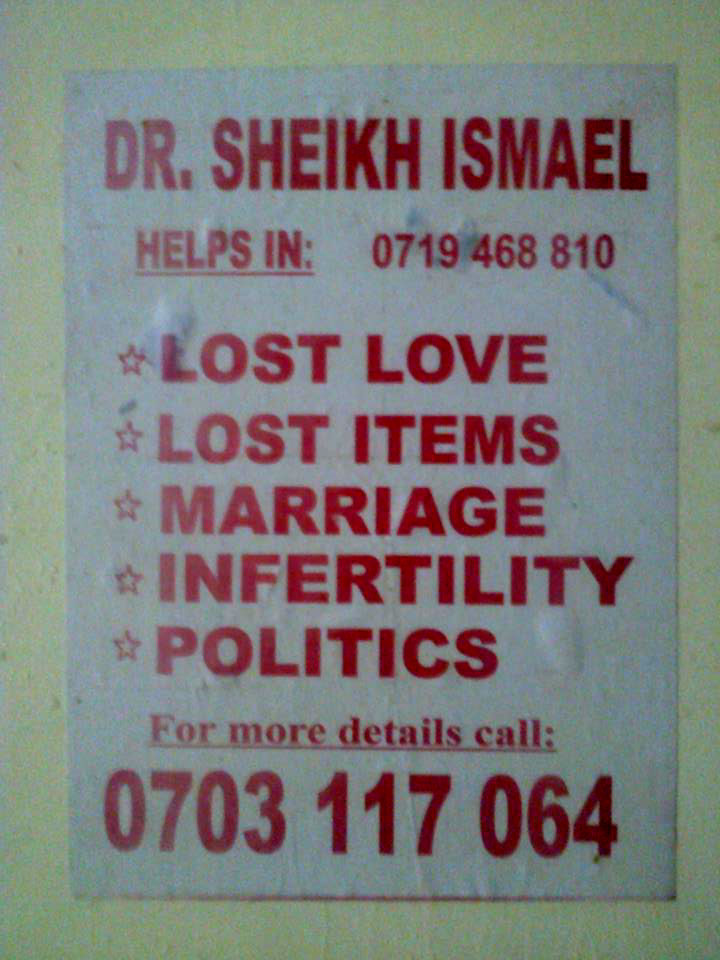

When I first arrived in Nairobi, I saw the signs but didn’t know what they meant. Once I started understanding Swahili, I learned that the profusion of ads, nailed to fences, stuck on poles and printed on A3 paper, were for waganga (witchdoctors) offering assistance mainly in matters of business, money, love and infertility. In just about every suburb of Nairobi, you’ll find at least one ad, hand-painted, on a little plate, nailed high up on a pole. For an average of around 6000 shillings (R600) you can get to see one of these mgangas but it is advisable to avoid those who advertise on paper. They are reputed to be con artists.

There’s a distinct undertow of witchcraft to the interpretation of many unusual events in Kenya. Even Christians, confronted by some unexplained phenomenon, might exclaim “juju!” (black magic) in the middle of the conversation, and usually everyone will agree.

There are two main ‘currents’ of witchcraft practised in the country. The first, often termed kamuti (kah-moo-teh), is attributed to the Kamba people. It is Bantu witchcraft, similar to that known in South Africa and involves the use of charms, ‘muti’ and spells to achieve the client’s ends. This type of witchcraft is heavily traded in the areas of Kitui and Kitale, not far from Nairobi.

The second stream of witchcraft derives from the Mohammedan influences in East Africa – from the Arabs who landed here centuries ago – and involves the deployment of ‘genies’ (as in Aladdin) to achieve one’s ends. It is grounded in texts from the Qur’an and here, you ‘rent’ the services of a genie to fulfil your wishes for you. You can even buy a genie to work for you permanently and exclusively if you have a few hundred thousand shillings at hand. This type of witchcraft is heavily traded in Mombasa, at the coast, and is reportedly common among the Swahili people. It’s even more strongly associated with Zanzibar, and Dar es Salaam on the Tanzanian coast.

Recently, a friend of mine was involved in a minibus accident. She was the only one without a scratch. The makanga (conductor) with a bleeding face wanted know where she got her juju from because he needed some.

Another friend’s sister was victim of a grenade attack at a church in Mombasa. Shattered glass went everywhere but she, standing at the window, was not injured. She said that people were muttering things about the protection afforded by genies. Interestingly, she was at church but had recently converted to Islam, not that anyone knew. Not anyone visible, anyway.

From the Bantu-Kamba kind of witchcraft there’s a tale so oft-repeated it has reached the level of urban legend. It’s the story of an unfaithful wife and her temporary lover who become “stuck” after having sex, like what happens to dogs. Of course, medical science refutes the possibility of this occurring among humans. But it happens – a YouTube video says so.

The clip shows a rather large woman and a rather small guy lying on top of her, unable to do anything to release himself. The woman is covering her face from the peering crowd, and the guy looks terrified. They are eventually released from each other when the husband comes into the room and does something to free them. One can’t see what he does in the video but the stories I have heard mention the uncapping of a Bic-type pen or the flicking of a Bic-type lighter.

Stories of “Nairobi girls” using this kind of witchcraft to secure a man is also legend. This kamuti involves the insertion of herbs or crystals into the vagina to keep the man abnormally attracted and emotionally ‘stuck’. The man will also be unable to gain an erection with any other woman. These kinds of stories are discussed very matter-of-factly in Nairobi. It is known to be a part of the girls’ personal arsenal, and is reputed to be a common practice.

Despite its widespread acceptance in Kenyan culture, witchcraft obviously has it detractors too. There have been horrific incidents of ‘witch’ lynchings – in 2009, five elderly men and women were burned alive by villagers in western Kenya who accused them of bewitching a young boy. Last year, The Star newspaper reported that elders in the coastal Kilifi Country were fleeing their homes out of fear of being killed for practising witchcraft.

Speaking to other Kenyans, mainly from the coast, I have heard stories of genies and what they can get up to if their master is properly paid and clearly instructed on the client’s wishes. I met a guy called Gilbert who told me he was forced to have sex in his car with a work colleague who had a crush on him. His brand new car refused to start and wouldn’t move when he tried to push it. Once he had done the deed with her, it started on the first turn.

During the mayhem that followed Kenya’s disputed election results in 2007, shops were looted and burned. A Mombasa youth grabbed a TV from a shop and escaped with it on his head. When he got home, he was unable to get the TV off his head. He only managed to remove it when he went back to the shop to return it. The clip isn’t on YouTube but millions of Kenyans saw it on national TV.

Skeptics will be wont to dismiss these juju stories as just that: stories. But before you do, let me add my own experience for light reflection: A few years ago, when I was researching witchcraft for a book I was writing, I was referred to an mganga based in Mombasa. He agreed to be interviewed on condition I undertook ‘rehma’ (spiritual cleansing) with him. I couldn’t resist.

I met the mganga at the Nyali bridge, just outside Mombasa. He looked very ordinary, wearing a plain shirt, khaki pants and flip-flops. He took me to a small, corrugated shack in the village of Bamburi. A fire was lit, molasses tobacco smouldered near it and incense was stuck in a banana to attract the genies. Evidently, genies like sweet things.

The ritual involved handfuls of rice sprinkled over me amid chants of a Muslim prayer. A goat was forced to inhale my recollection of negative experiences over a small fire and I was washed down by a live and wetted chicken. Salve (mafuta) was spread on my breastbone and applied to my palate and I left with little packets of sticks and ointment that I was to apply every morning to ward off evil. It took about 20 minutes in all, and I paid the mganga 8 000 shillings (R800) for the privilege. I didn’t feel any different afterwards, but the guy that had introduced me to the daktari (doctor) warned me that rehma would make me become “a magnet for women”. I laughed at the time and didn’t think any more of it.

I don’t consider myself to have any special appeal to women, but let’s just say that for the few weeks after my rehma, I had a torrid time of it all.

Brian Rath was born and raised in Cape Town. He now lives and writes in Kenya, and has a novel due to be published shortly.

Author’s note: Please be cautious of the claims and contacts that are provided in the comments section under this article. Readers have been given misleading information and have lost money. Exercise proper judgment.

Comments are closed.