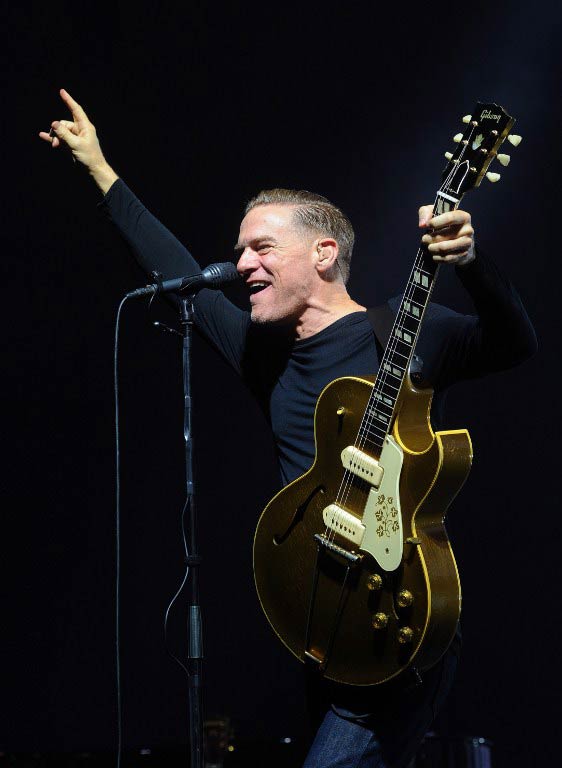

Tonight Canadian rock musician Bryan Adams performs at a sold-out concert in Harare which has, over the last few days, become less about the music and more about Zimbabwe’s strained political relationships with the west.

According to reports, the approximately 3500 tickets sold out within ten hours of going up for sale late last year. They are said to have ranged in price between US$ 30 and US$ 100.

Under normal circumstances, such modest figures might be overlooked. But this is Zimbabwe and if the reports coming out of the international media are anything to go by, Adams’ concert has the power to significantly assist in legitimising the autocratic leadership of the Zanu-PF government which returned to one-party rule through last year’s controversial elections.

This all sounds a little peculiar to me, especially considering that every now and then – contrary to what these recent media reports state – Zimbabwe has been known to receive a few international stars of repute. Joe Thomas, Sean Kingston, Ciara, Sean Paul and Akon have all visited Zimbabwe in the last five years. R Kelly is rumoured to be set to perform in Zimbabwe later this year.

Some of these artists’ performances in Zimbabwe, Sean Paul and Akon’s for instance, have been directly linked to campaigns led by the Zimbabwe Tourism Authority (ZTA), a parastatal which works closely with government ministries and is headed by Zanu-PF loyalist Karikoga Kaseke. In 2010 ZTA, working with other local initiatives, is rumoured to have invested over $1-million into hosting Sean Paul and Akon, who played at a once-off concert to an audience of over 20 000.

Interestingly the two came in for little, if any, scrutiny for being involved in this controversial concert. During the show, Sean Paul performed a rendition of Zimbabwe, a song written and performed for the nation by Bob Marley at Mugabe’s 1980 inauguration as prime minister.

From what is available online, it appears that Adams’ agent took advantage of the South Africa leg of his tour to explore the possibility of a performance in Zimbabwe.

The motivations thereof are unclear and I am not the right person to say whether or not they are political. But I will say it is unfortunate that so much effort has gone into angling what is – for the ordinary Adams fan – meant to be a good night out.

But can the ordinary Zimbabwean afford these tickets?

The insinuation again is that the auditorium will be filled with an audience of political bigwigs and Zanu-PF supporters because it is only those actively moving the party’s agenda who can afford to part with US $30 or more for this concert.

Every year, one of the biggest international festivals, the Harare International Festival of the Arts (Hifa), takes place in Zimbabwe. With most tickets ranging in price from $5 to $20, the average arts aficionado can expect to spend at least $50 on tickets alone over the duration of the week-long festival. Over the years, Hifa has had to answer many questions around the elitism of the event and its accompanying exclusion of the majority of Harare, and Zimbabwe. The festival – which attracts a large audience of white Zimbabweans – also brings into focus issues around race, access to resources and the arts in Zimbabwe.

It is therefore an unfortunate and reductive analysis of the state of affairs in Zimbabwe to assume that none besides the flag-waving and slogan-chanting can actually invest in having a good time. This analysis is not meant to gloss over the very real fact that the majority of Zimbabweans are living in the direst circumstances of poverty owing to Zimbabwe’s political and economic decline. It is not also not meant to cover up the many sins of those in political leadership who are looting and plundering the nation’s resources for personal gain and self-interest.

But it is intended to nuance the debate a bit. Because Zimbabweans can and do still enjoy and crave normal pursuits outside of the heavily politicised realm of party politics and sovereignty.

The idea I get is that this concert, through the person of Adams, will significantly alter the dominant narrative of autocracy and strife in Zimbabwe. But in case it was in doubt, US President Barack Obama this week sent a timely reminder that this won’t be the case soon, by ruling out Zimbabwe’s participation at the US-Africa Summit in August.

It’s not that simple.

So what is it about Bryan Adams that has attracted so much attention, and for such a small show?

The only difference I can make out between him and the other stars that I previously mentioned is that he is white.

Is there more at stake when a white international musician runs the risk of legitimising a black-led government that is known for delegitimising the rights of its white population? How did the Akon and Sean Paul case, with much clearer political links, attract less attention when they performed in Zimbabwe? Was it because that was when Zanu-PF was still within the power-sharing agreement with the MDC?

I hate to come up with conspiracy theories, but something about the coverage of tonight’s concert is off. And it has been off for many friends whom I have had this conversation with.

Many Zimbabweans aspire to more than being political pawns in a game of chess they neither sought nor control.

Let us have our concerts and dance.

Fungai Machirori is a blogger, editor, poet and researcher. She runs Zimbabwe’s first web-based platform for women, Her Zimbabwe, and is an advocate for using social media for consciousness-building among Zimbabweans. Connect with her on Twitter.