Following this year’s Oscar awards, the media was abuzz with John Travolta’s mispronunciation of an Oscar nominee’s name. He introduced Idina Menzel as the “wickedly talented, one and only Adele Dazeem”. American-born Menzel, whose ancestry is Russian and Jewish, subsequently laughed off this faux pax, calling it “funny“. However, Travolta’s actions are indicative of a wider and more problematic practice of westerners regularly butchering international names that they are not familiar with. It has become somehow excusable for them to consistently get it wrong – and many will not even make an attempt to pronounce the name correctly. When it comes to African names in particular, this propensity to towards pronouncing foreign names ‘any old way and how’ seems to increase.

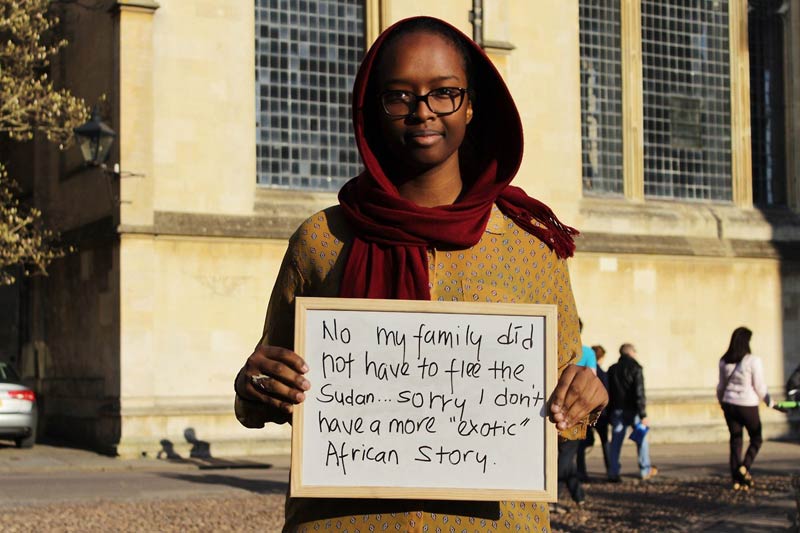

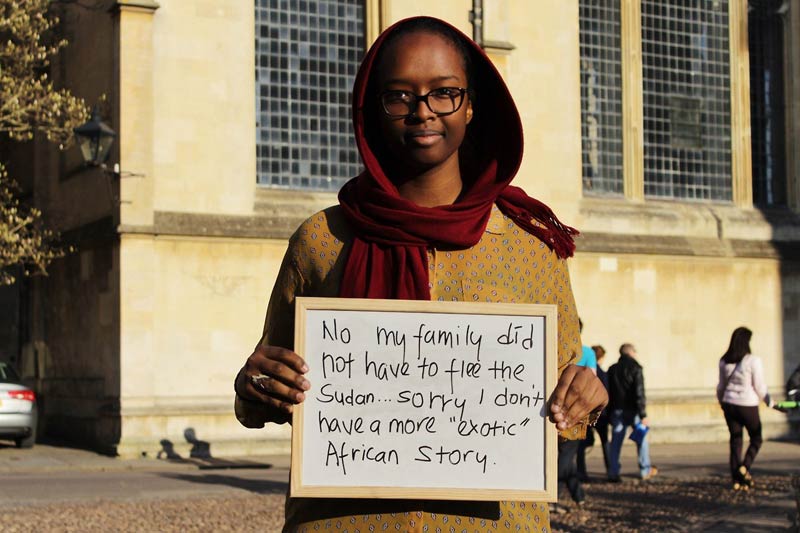

Africa has been treated with so much indifference over the years that a type of mental block emerges when Western journalists, talk show hosts, African country ‘experts’, and the general public are confronted with the African name. Africa is still very much the exotic ‘other’ in popular Western imagination. Therefore, names associated with Africa are perceived as somehow more exotic and different than other foreign names – leading to the perception that they are more so difficult to pronounce for Westerners. Consequently, it has become even more acceptable to accept the mispronunciation of African names.

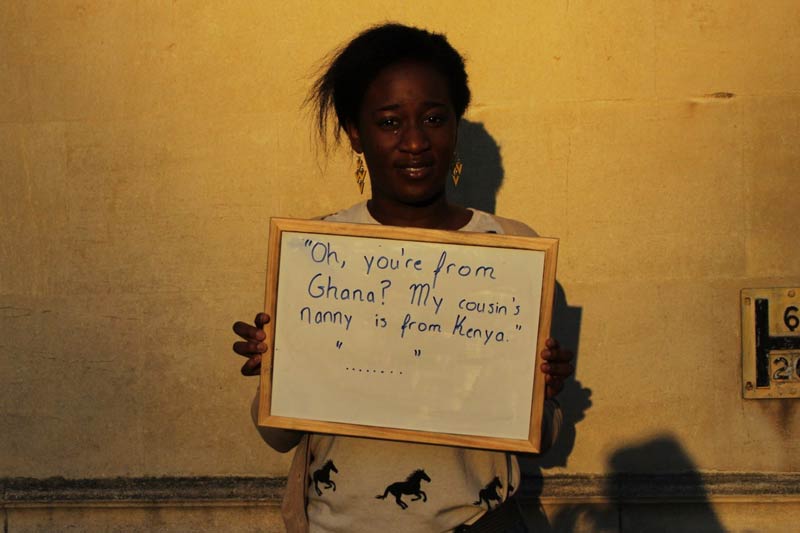

Typically, people take great care to make sure they pronounce another person’s name correctly unless they don’t care or they make the error deliberately. African names are consistently placed outside of these social norms because they are the African ‘other’. In Sigmund Freud’s studies, he noticed that the aristocrats would subconsciously mispronounce the names of their physicians more than any other group. This was interpreted as a way for the aristocracy to keep physicians in their place and remind them of their own social prestige. In doing so, they were also effectively relaying the message that doctors were not important enough for them to bother pronouncing their names correctly. The continued mispronunciation of African celebrity names sends a similar message. Therefore the common practice of pronouncing a stranger’s name correctly seems to be lost, either because Africans are the exotic other with “difficult” names or because an individual simply doesn’t care enough to make an effort to get an African name right.

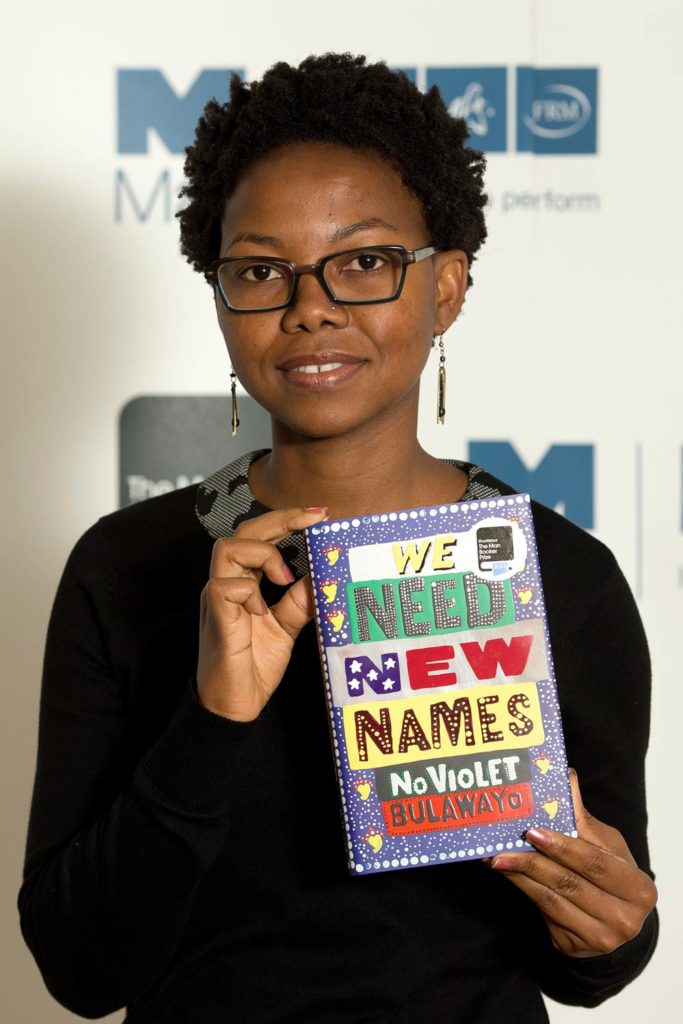

Lupita Nyong’o

While much attention was paid to the grotesque mispronunciation of Menzel’s name at the Oscars, few paid attention to the continued mispronunciation of Oscar nominee Lupita Nyong’o’s name. It’s mispronounced on a daily basis by people in American media that either don’t bother – or make a half effort – to learn how to correctly pronounce it. Some have argued that the mispronunciation of her name stems from the way it is spelled. The apostrophe in Nyong’o has proven to be troubling to journalists who are thrown off by it and often omit or misplace it. However, they have no problems with foreign apostrophised Irish names such as O’Reilly and O’Brien.

Western media has somehow taken to pronouncing Lupita’s surname with a hard ‘g’ as is commonly used in Germanic languages such as the word ‘God’ in English – or ‘Gott’ in German. When prompted, Nyong’o has repeatedly informed the media that the ‘g’ in her surname is a silent or soft ‘g’ – as with ‘song’ in English or menge (crowd) in German. Logically then, if you can say “Song of [Solomon]”, then you can correctly pronounce Nyong’o. Perhaps out of desperation over the mental block adopted by the Western public who just can’t seem to “relate” to the exotic silent ‘g’, Nyong’o has gone as far as releasing a video to guide the media. This fell on deaf ears as media experts continued to pronounce it the way that is most comfortable for them. So it was almost inevitable that on one of the biggest nights of her life, her name was announced by Austrian Christoph Waltz with a hard ‘g’.

If it’s African, I can’t pronounce it

Other African names such as Chiwetel Ejiofor, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and even Germanic African names such as golfer Louis Oosthuizen cause fumbles. Even African presidents are not immune. Many will recall how journalists struggled to correctly pronounce Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela and the name of his birthplace, Qunu. Those that could not pronounce these simply left them out. Omission seems to be a ready remedy to “difficult” names. Some may have noticed that the name of the so-called “fake sign language interpreter” at Mandela’s funeral, Thamsanqa Jantjie, was rarely used in media headlines and some television reporters avoided saying his name – they simply erased his name and hence identity.

In extreme cases, Westerners take insulting liberties with the pronunciation of African names to the point where they are not recognisable. Although he spent nine long months in the desert with Egyptian actor Omar Sharif, Irish actor Peter O’Toole did not make an effort to learn the stage name of his co-star. Rather than taking the time to ask him how to pronounce what can be considered a typical name for an African of Arab origin, O’Toole decided to call Sharif “Fred”, saying “no one in the world is called Omar Sharif”. His arrogant attitude is a clear example of how African names quickly become completely negated using ethnocentric lenses and justifications.

What’s in a name?

A person’s name is important marker of their identity and it should be treated as such. One’s name is of enormous significance to both the individual and the naming system in their society. The Ashanti in Ghana give names based on kinship, day of the week and circumstances surrounding the birth or occupation. The Yoruba in Nigeria, give names based on the physical condition of the baby at birth, birth order, the family’s social status or professional affiliation. In other cultures it may have religious significance such as warding off evil spirits. In the Senegalese Muslim tradition, names like Malik (King) have religious symbolism. Similarly, Mahmoud (fulfillment) – another popular North African Muslim – has significant meaning. Regardless of when, why, or where it happens, the giving and receiving of a name is of major importance. To simply omit or mispronounce them is extremely problematic.

Since one’s name carries such significance, people generally resent the mispronunciation of their name. It amounts to a distortion and misrepresentation of their identity. Accidental distortions or mistakes in pronouncing a name can be irritating. However, deliberate mispronunciations and distortions of a name – whether conscious or not – are sizable insults. As more African celebrities appear on the international stage, Western media should familiarise and educate themselves on how to pronounce African names correctly.

Sitinga Kachipande is a blogger and PhD student in Sociology at Virginia Tech. Her interests include Africana studies, tourism, development, global political economy, women’s studies, identity and representation. Follow her on Twitter: @MsTingaK