Wife-swapping among Namibia’s nomadic tribes has been practised for generations but a legislator’s call to enshrine it in law has stirred debate about women’s rights and tradition in modern society.

The practice is more of a gentlemen’s agreement where friends can have sex with each others’ wives with no strings attached.

Swinging with an African tribal touch? Or “rape”, as some critics see it.

The wives have little say in the matter, according to those who denounce the custom as both abusive and risky in a country with one of the world’s highest HIV and Aids rates.

But the Ovahimba and Ovazemba tribes, based mainly in this southern African country’s arid north, contend their age-old custom strengthens friendships and prevents promiscuity.

“It’s a culture that gives us unity and friendship,” said Kazeongere Tjeundo, a lawmaker and deputy president of the opposition Democratic Turnhalle Alliance of Namibia.

“It’s up to you to choose (among) your mates who you like the most … to allow him to sleep with your wife,” said Tjeundo, a member of the Ovahimba ethnic group.

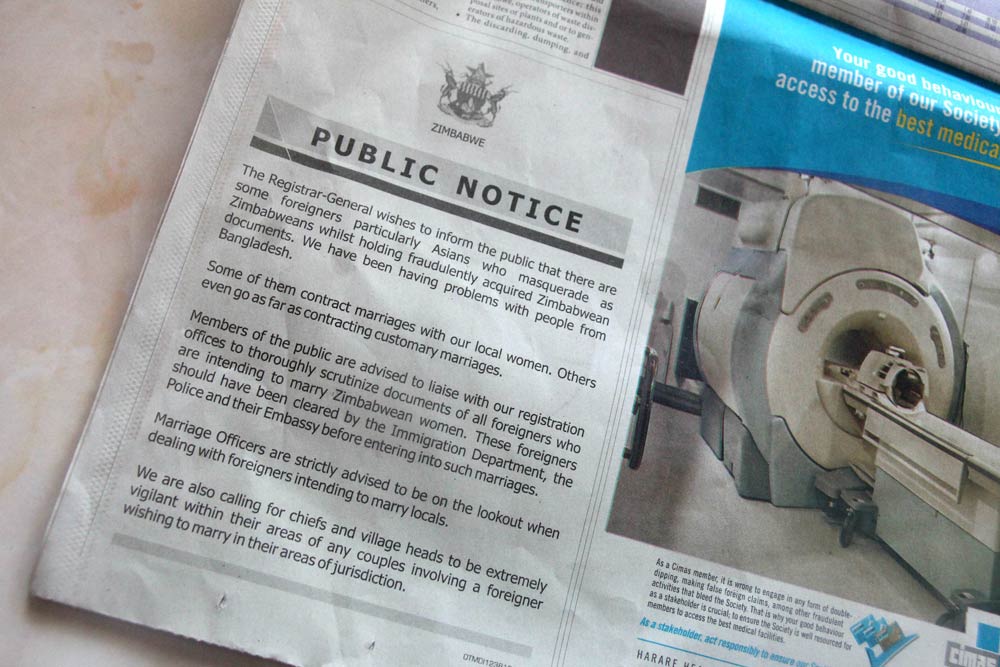

Concerned that HIV and Aids could be used as an excuse to stop the ancient tradition, he and others are suggesting regulations be adopted to ensure “good practice”.

Tjeundo said he plans to propose a wife-swapping law, following a November legislative poll when he is tipped for re-election.

Known as “okujepisa omukazendu” – which loosely means “offering a wife to a guest” – the practice is little known outside these reclusive communities, whose population is estimated at 86 000.

Mainly found in the northwestern Kunene region near the Angolan border, the tribes are largely isolated from the rest of the country. They have resisted the trappings of modern life, keep livestock, live off the land and practice ancestral worship.

Many still reside in pole-and-mud huts and both men and women go bare-chested.

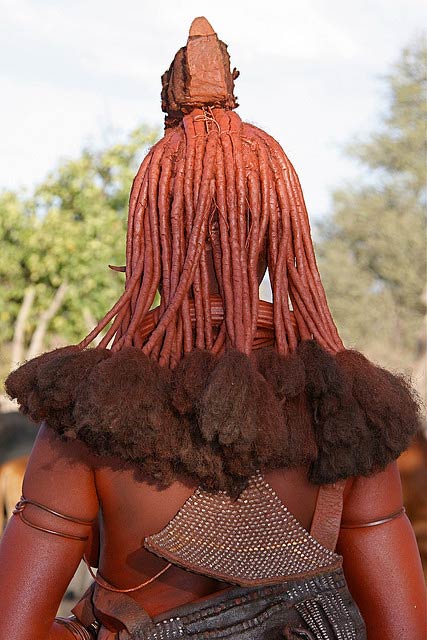

The women wear short skirts of goat skin, carved iron and cowshell jewellery and cover their braided locks in thick red ochre paste, which they also rub on their skin as a sun screen.

Unlike any modern-day swinging, tribal members make no random draw to pair couples. They meet in their own homes, while the husband or wife of the other party is banished to a separate hut during the exchange.

‘Not benefiting women’

Women cannot object to sleeping with a man chosen by their husbands, a point that angers rights activists like Rosa Namises who says the custom is tantamount to rape and “rape is illegal”.

“That practice is not benefiting women but men who want to control their partners,” said Namises, a former lawmaker who heads a non-governmental organisation called Woman Solidarity Namibia.

Other groups like Namibia’s Legal Assistance Centre (LAC), a public interest law firm that vows to protect the rights of all Namibians, have challenged its continued existence in a country where 18.2% of the 2.1-million residents have HIV, according to national statistics.

“It’s a practice that puts women at health risk,” said Amon Ngavetene, who is in charge of LAC’s Aids project. He contends that most women are opposed to the practice and would want it abolished.

But 40-year-old Kambapira Mutumbo is completely comfortable with the custom and has been asked to sleep with her husband’s friends.

“I did it this year,” she said, and “I have no problem with the arrangement.”

“It’s good because its part of our culture, why should we change it?” she added.

Cloudina Venaani, programme analyst with the United Nations Development Programme office in Namibia, is adamant that women only tolerate it because they are afraid of defying their husbands.

Traditionalists, however, insist the custom does not violate the rights of women, noting that women are also free to choose partners for their husbands – even if this rarely happens in practice.

Like opposition lawmaker Tjeundohe, Uziruapi Tjavara, chief of the Otjikaoko Traditional Authority in the Kunene region, wants the custom to continue but paired with education on HIV.

Details, however, are still vague.

“We just need to research more on how the practice can be regulated,” said Tjeundohe.

Shinovene Immanuel for AFP