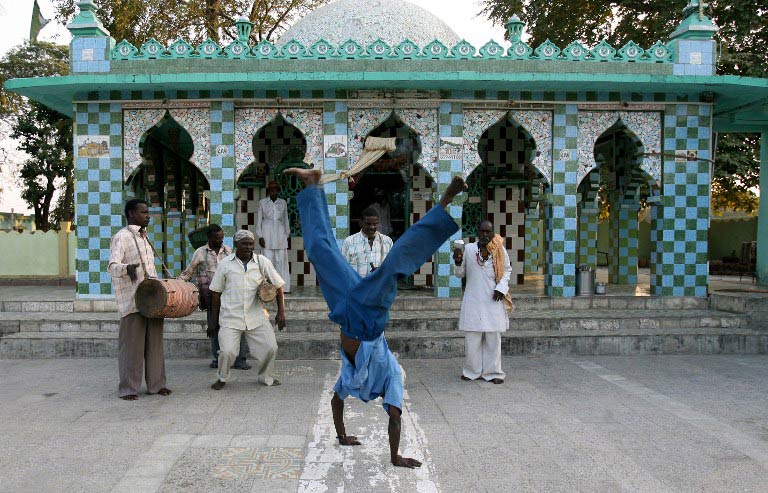

The tiny Sidi community, descendants of ninth century African migrants, have lived quietly along India’s west coast for hundreds of years while never losing touch with their ancient traditions.

A Certain Grace, a new book by Indian photographer Ketaki Sheth, reveals how the community, many of whose members live in poverty, has assimilated in India while keeping its distinctive culture alive.

At the book’s launch in Mumbai last month Sheth recalled her first brush with the community during a 2005 holiday in Gujarat state in western India.

“I first saw the Sidi in Sirwan, a village in the middle of the forest given to them by the Nawab [Muslim prince] … in recognition of their loyal services,” she said. “I was intrigued.”

Estimated to number between 60 000 to 70 000 in a nation of 1.2-billion, the Sidi originate from a swathe of East Africa stretching southwards from Ethiopia.

The fiercely proud community discourages marriage to non-Sidis and outsiders are unwelcome, as Sheth found out when she was greeted by a group of young men eyeing her suspiciously at the entrance to another village, Jambur.

“If looks could kill, honestly, I would be dead. I could sense irritation, hostility, perhaps even resentment to this very obvious ‘outsider’,” she said.

Two of those boys – “still angry and daunting” – would later turn up in a portrait shot by Sheth, their resistance apparently having faded over the five years she spent working on the project that blends portraiture and street photography.

Jambur would become an occasional backdrop to her photographs, all shot in black and white using a manual camera.

Often described as descendants of slaves brought to India by Arab and other troops, the Sidi mostly live in villages and towns along India’s west coast, with a few groups scattered across the rest of the country.

Anthropologist Mahmood Mamdani, a professor at New York’s Columbia University, says many came to India not only as cheap labour but also as soldiers, with some rising quickly through the ranks and even acquiring royal titles.

Successive waves of migration saw Portuguese invaders bring slave-soldiers from modern-day Mozambique to India, Mamdani writes in an introductory essay to Sheth’s book.

“Their main attraction was not their cheapness, but their loyalty. In this context, slaves are best thought of as lifelong servants of ruling or upper caste families,” he writes.

Those deemed most loyal were given land that is now home to villages inhabited exclusively by Sidis.

Reinventing African tradition

US-based academic Beheroze Shroff, who has studied the Sidi for years, told AFP that they, like other migrants, “have reinvented their traditions”.

Some customs have disappeared, while others, involving music, dance and the addition of Swahili words to the Gujarati dialect spoken in Sidi settlements have survived.

Shroff said that Gujarati Sidi Muslims in particular still practise “elaborate rituals and ceremonies, which involve drumming and ecstatic dancing called goma (a Swahili word that means drum, song and dance)”.

“This is handed down, learned by each subsequent generation, from childhood,” said Shroff, who teaches at the University of California in Irvine.

The Sidis, considered a marginalised tribe since 1956, have been the beneficiaries of affirmative action policies in India.

The Sports Authority of India (SAI) even launched a special Olympics training centre in Gujarat in 1987, in an attempt to capitalise on the athleticism of the African-origin Sidis.

That experiment ended nine years ago amid reports of petty politics and infighting among administrators but it produced a string of national-level athletes, such as Mumbai-based Juje Jackie Harnodkar, featured in Sheth’s book.

Harnodkar is among few Sidis belonging to the middle-class. Most struggle to find jobs and literacy levels remain low as many can only afford to send their children to poorly-managed state schools.

And many children like Sukhi – a young girl whose portrait is Sheth’s favourite of the 88 photographs featured in the book – attend school infrequently.

“She did go to school when I last met her but very erratically. She must have been 10, 12 when I took that photo [2005]but when I asked her she wasn’t sure,” Sheth told AFP in an email.

Sukhi’s striking portrait, her eyes downcast, her curly hair askew, was taken on Sheth’s first shoot in Jambur, she said.

“The early morning light was flat because it was pre-monsoon, the bricks and cement behind her were static and graphic, and her stripey dress seemed to move like a river even though she was so still.”

Ammu Kannampilly for AFP.