One of the most popular shows on Ghanaian television in the 80s was Obra. A common scenario in the show was that a young teenage girl would get involved in a relationship with a man and inevitably fall pregnant. This would lead her to drop out of school, the man who had impregnated her would abandon her, the young girl would become an embarrassment to her family, and the rest of her life would be a misery. Whenever we watched this happen, my mum would turn to me and say: “You see what happens when you mess around with guys?”

That was the type of sex education I received growing up in Ghana. Sex as taught to my generation of Ghanaian girls was always ‘bad’, and only ‘bad’ girls had sex before marriage. At the boarding school I went to there were always rumours about the girls who apparently had sex – they were called names like ‘Kaneshie mattress’, suggesting anyone who lived in that area of Accra had slept with them. I myself always believed these rumours about the ‘bad’ girls. How could you doubt stories told with such confidence? It was only when rumours about my own sexuality reached my ears that I began to question these myths.

After a growth spurt one summer holiday, I returned to school with gigantic boobs. One day while walking to my dorm, I overhead a group of girls chatting. “Have you seen Nana Darkoa’s breasts? They have gotten so big. It means she had sex during the holidays,” one of them said. As if that wasn’t bad enough, the following summer a male friend of mine told my boyfriend that he had “fucked me in the gutter by my house”. That was when I stopped believing the ‘bad’ girl myth.

Fast forward to my early 20s. My knowledge of sexuality hadn’t improved greatly. Yes, I had been sexually abused as a child. Yes, I had kissed girls in my boarding school. Yes, I had kissed a boy for the first time in the summer before my O-levels and gone on to kiss two other boys that same summer, but I still knew nothing about sex and sexuality. Until I went to university abroad I had no idea that girls who kissed girls were called lesbians. In my boarding school we called our girl lovers ‘dears’. (Not everybody who had a dear had a sexual relationship with their dear. Having a dear implied an added closeness and relationship with a certain girl/young woman. Your dear, for example, could be a fellow student in your year or a senior who had propositioned you).

I was an avid reader of romance novels while growing up. I would wrap the salacious covers of Mills & Boon, Harlequin and Silhouette novels with old newspaper and read furtively in between classes or in my bed at night. These novels taught me that women could have unimaginable pleasure when tall, dark handsome men ‘took’ them, but they didn’t break down how exactly this happened. When I was 20 and living abroad with my best friend, she seemed wildly mature to me because she was sexually active with her boyfriend and would walk around our shared flat naked. One day she asked me if I ever masturbated. I was beyond embarrassed. She used to tease me that I was going to remain a virgin until I turned 30. When I met my future husband two months shy of my 23rd birthday I knew instantly that I wanted to have sex with him. That was when the process of learning about sex and my own sexuality began. It is an ongoing journey of sexual self-discovery.

Starting Adventures from the Bedrooms of African Women in 2010 has been an important part of documenting my own sexual journey. The blog has created a space for African women to learn from and share our stories of sexual agency and the horrific experiences of abuse and sexual assault that have attempted to take away our power.

I was inspired to start the blog after a life-changing holiday to Axim in the western region of Ghana. I was with a group of three other African women. One evening while lounging around the beach we began a frank and open conversation about sex, which continued throughout the holidays. We talked about our sexual experiences, reminisced over past relationships, recounted good and bad sex, and shared our fantasies. I was buzzing with excitement when I got back and rang my best friend in the US.

“Malaka, I’ve just come back from holiday and I had the most amazing time talking about sex. I think we should start a blog about African women and sex.”

“Ha! Its uncanny you should say that. I was just thinking of writing a book called ‘Adventures from the Bedrooms of African Women’. If only people really knew what went down in our bedrooms.”

We split our sides in laughter. We laughed because we knew that the images people had of African women’s sexuality were myopic. We recognised that people saw us as victims of female genital mutilation and sexual subalterns or, on the other extreme, as over-sexualised women with extra-large genitalia to boot. We laughed because we knew our stories were more diverse than the outside world knew. We laughed because we knew we were continuously negotiating our sexual agency, while battling with the traumatic effects (in some cases) of child sexual abuse. We laughed because this was our opportunity to tell our own stories.

And that’s exactly what Adventures has succeeded in doing. The blog, which receives about 35 000 visitors a month, is a safe space for African women to share experiences around sex, sexuality and relationships. Many contributors remain anonymous because of the social censure that surrounds women who express their sexuality openly. Readers have told me that Adventures has enabled them to have open conversations about sexuality that they were never able to have with parents, friends or in school. At Ghana’s first Social Media Awards in March, Adventures scooped awards in the categories of ‘best overall blog’, and ‘best activist blog’. I felt especially proud that people recognise that providing a safe space for African women to talk about their sexualities was an act of activism.

African women across the continent and diaspora have boldly taken ownership of the site and share their stories of sexual fantasy, sexual experience and sexual abuse. The site’s policy has been to focus on women’s stories, while allowing the occasional contribution from African men. Roughly 60% of our readers are women while 38% are men and 2% identify themselves as transgendered. One of the most popular posts on Adventures is on how to pleasure a woman orally, written by a male contributor. There are other posts that have aroused anger and sadness and highlighted the need for supporting survivors of sexual abuse. These stories and the large number of comments they inspire show that comprehensive sexual education is important not only for women (and men) to gain bodily confidence and an understanding of their right to sexual pleasure, but also so that children do not grow up with a sense of shame around sex, which can lead to silence when sexual abuse occurs.

The fact that most of the stories on Adventures are based on women’s personal experiences refute popular myths such as homosexuality being a Western import. Here’s one comment from a reader:

It’s very refreshing to find like-minded individuals who speak so freely and openly about homosexuality. I think I’m bi-curious. I have crazy girl crushes and love lesbian porn. Having never been off the shores of Ghana, you know the general perception about these things, so I’ve never really talked about it to anyone .

Now run and go tell that to the African conservatives who claim that homosexuality is un-African.

One of the most popular contributors to Adventures goes by the moniker Voluptous Voltarian. She shares:

The reason why I started reading and writing for Adventures was because the very first comment I read was from a man. I realised that Adventures had created a space where African women and men could have an honest conversation outside of a regular face-to-face context where negotiations about sex can be very conflicted and transactional. I think that’s the real revolution. Adventures provides the space for people to work through this conflict, and for people to be their better healthier sexual selves.

Personally, I am still working on being my best sexual self. I choose to do this openly in a world that still judges women for the sexual choices they make; in a world where calling a woman politician a ‘prostitute’ does not provoke the kind of widespread criticism I hope it would. I do this in a country where the Ghana Journalists Association recently exhorted journalists to adopt an anti-gay stance in their work. As a single African woman I choose to blog openly about my sexual life in order to create community with other African women who were also told that having sex outside of marriage would automatically lead to pregnancy, familial disgrace and a subsequent life of ruin. Today it makes me incredibly proud that our sexual revolution is being blogged.

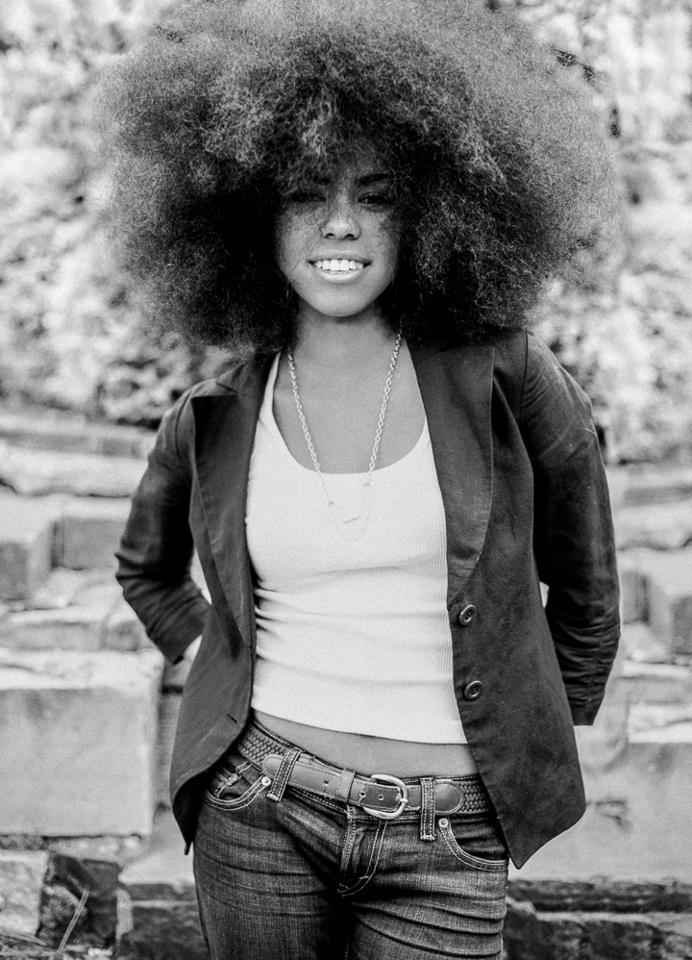

Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah works as a communications specialist at the African Women’s Development Fund, is co-owner of MAKSI Clothing and curates the Adventures from the Bedrooms of African Women blog.