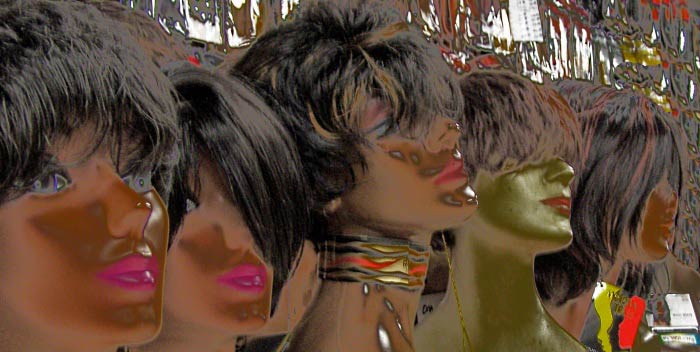

It is Wednesday afternoon in Gaborone and I am having a bad hair day. I head into town to see my hairdresser for my monthly haircut. I have deliberately set my appointment for midweek to avoid the mayhem that happens on weekends in the hair salon. As I stride in, behold, four beautiful ladies ALL getting their weaves on. There was a rather colourful assortment of hair pieces ranging from black Brazilians to blond fringes. It suddenly dawns on me that the legend of the weave ladies might be true after all: they prefer visiting the salon smack in the middle of the week when everyone else is at work. Reason? Their obsession with the weave has cost them their hairlines and so they do not want anyone but their hairdressers to witness the calamity that has hit their pretty heads.

They say imitation is the highest form of flattery. We live in the “hair piece” era and in Botswana many young women do not grow their hair naturally anymore, but instead go out of their way to wear hair that belongs to Brazilians, Peruvians, Malaysians, Mongolians and many other nationalities on their heads. What happened to good old dreadlocks, the afro or even plain straightened hair which can be braided every now and then? Why do we want to imitate members of other races when the African race is so beautiful? Are we losing our identities to the weave craze? Have we been corrupted into conforming to mainstream standards of beauty and femininity, believing that we can’t be beautiful if we wear natural hair? Fake it til’ you make it is the motto.

Being a member of #TeamNatural, chances of me donning a weave are slim to none. I will admit that I did try it out once, out of curiosity. And it is suffice to say my affair with the hair piece ended a week later. I just couldn’t stand the itching and the constant head-patting. It felt like dozens of mosquitoes had purchased real estate on my scalp! And the inability to scratch made it even worse. So I decided to leave it to other ladies, concluding that experience has taught them to handle the discomfort better.

I have no problem with the weave; I just have a problem with natural hair being vilified. Are we going to pass down negative perceptions of black hair to generations after us so they become ingrained in our children’s mentality to the point where they will be accepted as simple truths?

For many black women, the weave is probably the next best thing after high heels. In many parts of Botswana, especially the urban areas, the weave is not just a trend, it’s a lifestyle. It looks really good and boosts a girl’s confidence if sewn on right, making her look and feel like an African queen. The problem is the hair looks so fake it could melt under the merciless Botswana sun.

From itchy scalps and patchy hair loss, these inventions not only cause premature balding but they cost big bucks. The men say they hate it – for two reasons: 1) they want to be able to run their fingers through a woman’s hair without their hand being smacked and 2) 80% of the time they have to pay for it.

I asked one of my friends who has embraced the weave craze about her choice. She said the appeal of it lies in how it makes her feel – sexy, stylish, expensive. “You don’t look basic. And going to the salon often to get it done is one of the few ways of pampering myself, just like getting my nails done or having a massage,” she explained.

Most races – Asian, Caucasian, and Hispanics etc. – have no problem wearing their hair as is, but in black culture it’s looked upon as subversive. That’s not to say that other races don’t change or play around with their hair (white women wear weaves and call them extensions). However, it becomes concerning when we measure self-worth by what kind of hair we wear – or don’t wear.

Maybe one day, we African women will evolve to a level where we are proud of dark skin and nappy hair; to a level where society deems wearing natural hair as a progressive statement for everyone – not just for poets or the “artsy” or “afrocentric” types. Maybe one day our hair in its natural state will be a symbol of African pride.

Rorisang Mogojwe is a features writer in Botswana.