I’m still trying to make sense of it. There are days when it doesn’t feel real, days when I can’t quite convince myself that it happened. It is on these days that I find refuge in the past, in the years of political asylum around which my entire life has been framed, the time when all we wished for was freedom. Be careful what you wish for, they warn. But of course, this has never stopped us from wishing.

I was born to a Libyan man and a Libyan woman who decided early on that as long as a madman ruled Libya with a bloody fist, we simply could not live under his thumb, and neither could we accept that fate for our aunts, uncles, cousins and countrymen. My father brought his young wife and my older sister to California in 1974 on a student visa to study soil science and agriculture in America’s big and bright universities. I was born in the same state. After a brief return to Libya, we moved back to America in 1981, and we would never return to Libya again. At least, not as a family. Not with Dad.

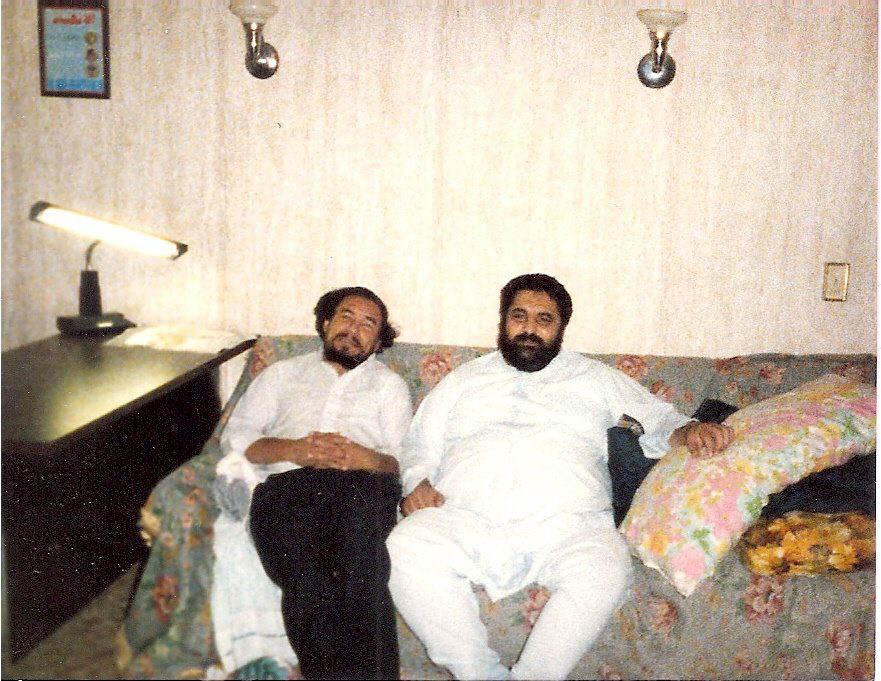

My father, a gregarious, witty, passionate Libyan from the mountains of Gharyan, joined the National Front for the Salvation of Libya (NFSL), one of the first and largest of the dissident organisations against Muammar Gaddafi. When we thought he was on graduate school field trips to California, he was actually in Chad, recording sessions of a pirate radio program where he played the role of “The Patient Pilgrim” – clippings of erratic Gaddafi speeches interspersed with my father’s colloquially scathing commentary. My grandmother, unaware of his dangerous political activities, listened religiously to these programs – a rare voice of clarity in a country ruled by maniacs – oblivious to the fact that the outrageous firebrand reducing the “Brother Leader” to a political punch line was her errant son who could never give a good reason for why he hadn’t returned home for a visit. I witnessed many of these long-distance phone calls as a child – my mother wringing her hands, my father rubbing his forehead as my grandmother’s pleading voice came over the scratchy line. “Why haven’t you come home? How long do I have to live? I will take my last breath before I see you again.” “Soon, soon, Insha’Allah (God willing),” he would promise, again and again. He could not tell her why he couldn’t come home. And “soon” would turn out to be a broken promise.

We couldn’t go back even for a visit, of course. The Libyans who would join the NFSL would be branded “wild dogs” by Gaddafi, their members hunted down and assassinated, their families in Libya financially punished, imprisoned, hanged. Libyans living abroad avoided associating with active dissidents even though they were similarly politically aligned, knowing that to be tainted with that association would have very real repercussions back home from Gaddafi’s far-reaching spy network of informants.

But I didn’t know all of this, not in Oregon, swimming in a lazy creek, or swinging from the large oak tree that stood anchored by thick rolling roots in the centre of the graduate school housing where I spent my childhood. At the age of 14, my father moved us from our little collegiate haven to Kentucky, where we joined the larger group of NFSL families living in the heart of Bluegrass Country. It was here that I finally felt I was part of a community of peers. Libyans from Tripoli, Benghazi, Zawya, Misrata, Zintan, Derna – all these names now made familiar by endless news updates from the war – came together after years of displacement as Gaddafi made alliances with previously hospitable government hosts. America was the last refuge. We were corralled, far away from Libya’s immediate borders, just like Gaddafi wanted. The wild dogs were no longer nipping at his heels. But they continued to growl, even as infighting eroded our numbers and Western rapprochement left us without powerful sympathisers, if not allies. And through it all, my father represented all that was good about Libya: dignity, honour, faith and relentless optimism in the face of certain defeat; an optimism born of undying faith in a higher power.

We did not buy a house. Our cars entered our garage within months of their demise. Everything good would be saved for ‘home’. Boxes of plastic flowers, pretty dishes and colourful curtains sat collecting dust and going out of style while awaiting use in the life that was to be lived only in Libya. Existing in a perpetual state of asylum meant that we never really lived life to the fullest, but it also meant that we never lost an integral connection to a country and culture that most first-generation expat Libyans had, despite never having stepped foot in their homeland. Our social gatherings centered around our anti-Gaddafi activities. We signed petitions, drafted constitutions, printed magazines, demonstrated at embassies. In between these efforts, we struggled to deal with the pain of missing family weddings, family funerals, every holiday celebration. Brothers and sisters joined our growing family, even as my hopes for ever returning to a free Libya diminished.

In the end, it would not be Gaddafi that killed my father, but stage 4 glioblastoma multiforme. It was in the cold winter of 1994 that he was diagnosed with an aggressive terminal brain tumour. I was 18 years old, and I had never known anyone who had died. My father would be the first. That’s what happens when you are a political refugee – you miss out on the normal parts of life, the good and the bad, leaving you ill-prepared to deal with them when life happens to you. As the cancer spread, he could not walk unassisted and had to be fed, bathed and cared for around the clock by my stoic mother.

The jarring loss of life as I knew it came into clear focus when I brought up Libya one day, telling him about a demonstration or some such event. He didn’t let me finish. “I don’t care,” he said. I sat stunned, dismayed. This was the man who devoted his entire life to this cause – gave up his olive trees, the sage-covered mountains dotted with grazing sheep, the camaraderie of brothers and sisters, nieces and nephews – and it was all dismissed with those three words I had never heard him utter before. “I am dying, Hend.” Death, the great equaliser, had already shifted his priorities. Gone was my anchor, my motherland, my ancestors, my past, my future – all wrapped up in the single symbol of my identity and raison d’être, my father. My world crashed around me, in a fog of doctors’ visits and physical therapy for a dying man. We buried him 13 months later, next to a small Japanese maple in a cemetery far away from where he was born.

I don’t resent cancer. Cancer kindly gave us over a year to get used to the idea of death. And as it turned out, he never really left. As I grew older and had my own daughter who started asking me “How can I be a Libyan, if I’ve never been to Libya?”, I heard my father’s voice in my answers. I’m sure he smiled when I looked into her eyes and said: “We can’t go back until we stop a bad man from hurting our country, from stealing from her people.”

He sat close to me when I followed the unfolding of events in Benghazi, Tripoli, all the cities where Libyan men and women freed from fear faced Gaddafi’s bullets so that those standing behind them could lead the second charge for freedom. He held me tight as I cried on October 23 2011, when independence was proclaimed in a newly freed Libya. And when I finally returned to Gharyan this summer, after decades of absence, he sat next to me on the rocks along the path to the well he would use to wash up before performing his daily prayers. I scanned the horizon, passing over homes, well-worn paths, twisting olive trees … it was all so familiar. It felt like I’d never left. And I knew, then, that my dad had brought me home.

Hend Amry is an artist and freelance writer, living in Doha, Qatar with her husband and two daughters. Follow her on Twitter.